By Yolanda C. Urrabazo

While living in Mexico in the aftermath of the Mexican Revolution, Abraham Moreno developed a strong value of hard work at a young age.

His good work ethic was soon implemented when he arrived in the United States as World War II developed.

Moreno was born in 1912 in Monterrey, Mexico, one of nine children. His father, Abraham Moreno Villarreal, had been a merchant and a winery administrator through the difficult years of Mexico's war. Abraham lost his fortune because of the revolution, Moreno says.

"At that time ... there was a lot of turmoil in Mexico," Moreno recalled.

The family's difficult financial condition worsened after the elder Moreno died in 1924. Work became Moreno's only option, so he quit school after the fifth grade.

"My mother was just struggling to survive," he said.

At 12 years old, Moreno started work at a furniture factory, where he learned about the manufacturing process. After 10 years of work in the industry, the ambitious young man was ready to learn a new craft in an emerging field. In 1935, he traveled to southeast Mexico and got a job repairing and maintaining old airplanes. His salary was 700 pesos a month, just enough for room, board and a few personal living expenses. Part of Moreno's work involved recovering planes that had crashed in various areas of Mexico. Temporary repairs were made in the jungles or mountains and were flown back to their bases regularly.

"There were a lot of crashes all the time," he said, attributing the failures to poor maintenance and the use of second-hand parts.

On two occasions, Moreno survived crashes on his way to make repairs.

Even with the relatively high wages he earned as a superintendent of maintenance, however, it was difficult to prosper in Mexico.

"Even though I had a very good job over there, [I] couldn't get any higher," said Moreno, who craved being immersed in the latest aviation technology. "And my wish was to work on American airplanes."

So he didn’t hesitate when Mauldin Aircraft in Brownsville, Texas, the company from which his company bought parts, recruited him. Moreno was afforded the opportunity come to the U.S. because Les Mauldin, the owner of Mauldin Aircraft, was losing workers, not only to larger companies, but to the war.

Moreno arrived in Brownsville on August 7, 1941, to replace another man as chief mechanic. He was paid $22 a week in the U.S., but never considered money to be a major driving force.

Thinking about himself as a younger man, he says he knew that rather than the money, he wanted to study and get his A&E (Aircraft and Engine) Mechanic's License.

After about three months of working at Mauldin, Moreno was offered his previous boss' job in Mexico. But he didn’t consider the proposition because he was determined to stay in the U.S. to invest in a "better future." Moreover, his American boss sweetened the deal by doubling his salary.

Moreno was exempt from the draft because of a childhood leg injury, so he was able to remain focused on his personal goals. As he worked, he attended night school while also studying mechanic textbooks.

"The combination of going to school to learn English and trying to learn the mechanical stuff ... kept me working hard," he said.

It took Moreno two years to completely adjust as a newcomer. He passed a 600-question mechanic's test, which finally granted him his Mechanic Certificate on June 21, 1944.

During the time of war, Mauldin bought and sold airplane parts and also played a helpful role in preparing prospective pilots, as Mauldin's Civilian Pilot Training School taught the intricacies of aircraft mechanics to young men.

"We used to have a lot of guys that went to work for us as an apprenticeship, and then they went to the Air Force," Moreno said.

A large part of training was centered on pilots, but participants also became well trained in fixing major and minor problems on aircrafts. Learning this aspect of aviation was useful for future Air Force pilots when in an emergency situation at war.

Moreno remembers a country brought together most noticeably during wartime.

"Everyone was very patriotic -- the aliens, the citizens, the residents were all for the war," he said. "There was no dissension."

In the private sphere of home life, people felt the repercussions of the conflict.

"Everyone respond[ed] to the effort and we used to suffer along the consequences at home," Moreno recalled.

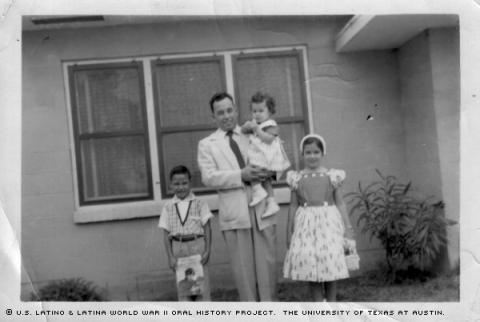

In 1944, Moreno married Julia Resendez, whom he met through a coworker at Mauldin. The young couple had their first child, Maria del Socorro, in 1946. That same year, Moreno left Mauldin and began emergency crew work for Pan American Airways.

With Pan American, he repaired C-46 cargo aircrafts in distant places such as South America. He was once sent to Bolivia with two other men to fix an aircraft deep in the jungles.

"We worked for about 12 days, nine to 12 hours a day, and got the airplane fixed to where we could fly it," he said.

Their only chief concern in the area was tribal groups; the insurance company even required the men to carry pistols in case of problems. Without any difficulty, though, the men flew the plane from Santa Cruz, Bolivia, to Brownsville, Texas.

Pan American eventually sent Moreno and his family to Miami in 1948, where he worked for almost three years.

"[Florida] was a very good place to live. All the people were very nice," he said.

As his first two children were growing up in Florida, they were taught Spanish at home while learning English through their neighborhood friends. Moreno doesn’t recall many Cubans being around at that time, but does remember a lot of Jews.

On April 12, 1951, he finally obtained U.S. citizenship in Florida. When Pan American closed its base in 1959, he started working with Intercontinental Engine Services until he retired in 1974.

All six of his children are college-educated.

"[E]ducation is key" for anyone living in or immigrating to the U.S., Moreno said.

Mr. Moreno was interviewed in Brownsville, Texas, on September 13, 2003, by Yolanda Urrabazo.