By David M. Ramirez

On June 6, 1944, Staff Sergeant Adolfo Roberto “Rusty” Ramirez was a member of the largest invasion force in all of recorded history. He was assigned to the 29th Infantry Division, 116th Regimental Combat Team’s 121st Combat Engineering Battalion. The 29th and 1st Infantry Divisions had been given the mission to assault Omaha beach in Normandy, France. Of this 55,000-man combat force assigned to Omaha beach, the 116th Regimental Combat Team of the 29th Infantry Division was assigned to land at Zone “Dog Green.”

Ramirez had been training for the invasion for more than two years at Tidworth, England (specializing in demolition and getting specialized training in the “Bangalore torpedo,” a device designed to roll up barbed wire barriers), after having occupied Belfast, Ireland, to keep it from being seized by the Germans. Just prior to the invasion, Ramirez and his buddies in the 29th had been placing bets on the day of the invasion, and he recalled he came the closest, guessing June 5th.

The 29th and the 1st Infantry Divisions were the spearhead units that landed on Omaha Beach June 6, 1944, otherwise known as D-Day. Ramirez was supposed to have been in the first wave of the 29th that landed on Omaha, but as luck would have it, he was reassigned to the third wave to land on Omaha that day.

Omaha Beach was defended that day by the veteran German 352nd Division, and they had carefully constructed their machine gun, mortar and artillery emplacements to cover every inch of the area. From his tank landing ship, Ramirez witnessed the first two waves of soldiers being annihilated.

“Time seemed to stand still,” said Ramirez in his 1984 interview, “men were dropping like leaves.”

The third wave disembarked in water too deep to wade in; thinking quickly, Ramirez took off all of his gear, more than 100 lbs of equipment, including his helmet, and jumped over the side to swim to shore.

It was “a blessing to get knocked down” by the waves as he made it to shore, he recalled.

When Ramirez got to shore, the first thing he did was get an M-1 Garand rifle from the many no longer needed by his dead comrades; men began to rally one another to return fire and gather for an assault to get off the beach. Night fell and he waited out the first night on Omaha beach. Ramirez recalled the cries of his wounded fellow soldiers throughout the night.

“They were asking for their loved ones and begging for mercy … it was like a nursery with a bunch of babies crying, only these were adults. That’s a big difference. It was a helpless situation – really, really helpless.’

Ramirez remembered the sentiment he had while working his way up Omaha beach under machine gun and mortar fire.

“Oh, it was a terrible feeling. You are out there by yourself. It is almost a feeling of utter frustration because you know people are dropping right and left of you and you don’t realize that maybe the next bullet might hit you. Here’s buddies that you’ve trained with for over two and a half years, and I saw some, that on that attack, their lives were swept up in the span of a few seconds.”

In spite of the murderous fire from the 352nd, the survivors reorganized and (with the help of Air Corp strafing and naval shelling) captured the cliffs overlooking the beach, securing the road to Isigny, which enabled them to secure the beachhead. More than 50 percent of the soldiers of the 116th Regimental Combat Team were casualties that day; 50 percent of the soldiers in Company B were killed, 96 percent in Company A. Ramirez said every day of his life after June 6, 1944, was a blessing.

Ramirez and the rest of the 29th went on to claw their way through hedgerow country around Argentan (with the aid of hedgerow-penetrating tanks designed by an Army sergeant) to participate in the Battle of St Lo and the Battle of the Falaise Gap, which Harpers Magazine called one of the most crushing and least known of the United States’ World War II victories.

The Falaise Gap was a pocket of land between the towns of Tun, Argentan, Vimoutiers and Chanbois, in which the last of the German 7th Army was surrounded by Allied forces. Ramirez recalled that it was a crucial battle.

“The Germans realized that if the 7th Army was annihilated, they would have no defense left,” he said.

The battle was fought by American, Canadian, British and Polish Forces, and involved heavy artillery and the use of many fighter bombers from the Royal Air Force and U.S. Army Air Corps. The result was approximately 50,000 German Prisoners, 15,000 Germans killed and the loss of more than 730 tanks and hundreds of other vehicles and artillery pieces. Ramirez recalled there was “Nothing but mile after mile of dead Germans,” and that the Germans suffered at least 15,000 casualties. The unbearable odor of dead soldiers could be smelled from five miles away. “We had to pour cognac on a cloth and hold it over our noses because of the stench,” he said.

Ramirez and the rest of the 29th were then attached as reserves to General Patton’s Third Army and participated in the crossing of the Siegfried Line.

When the Nazis surrendered May 8, 1945, the soldiers savored cognac differently, this time in celebration, which Ramirez recalled lasting a week, like the liberation of Paris. The joy proved ephemeral, however, as there was still work to be done in defeating Japan.

For his service, Ramirez earned multiple awards, including France’s Croix De Guerre with Palm, (which he was authorized by the American Defense Department to wear, the same thing as being awarded the medal by the U.S.), three Bronze Battle Stars (for Normandy, the Falaise Gap and the Crossing of the Siegfried Line), the Arrowhead Award (for Landing at Omaha Beach on June 6, 1944), The World War II Victory Medal and the Marksmanship Award. Moreover, Ramirez and the entire 121st Combat Engineers were awarded Four Presidential Unit Citations, a senior unit award granted to military units performing extremely meritorious or heroic acts in the face of an armed enemy. As the Army Chaplin said at Ramirez’s funeral, “To those who fought, he was among the best loved of soldiers, an engineer, because they are the first in and the last out.”

Ramirez never traded on his military service. He felt the real heroes were the ones who had given their lives and their futures. All during the 1950s, when his three children were growing and they would ask what he did in the war, all he would say is, “I was in the Army, but remember, there are better endeavors than war.”

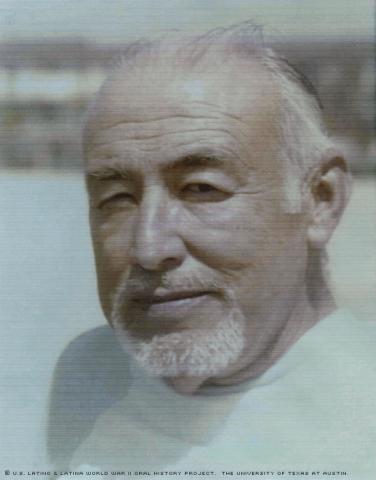

In 1984, Ramirez suffered a massive heart attack; while he was in delirium, his son, David M. Ramirez, learned of some of what happened to his father during WWII. So when the 40th Anniversary of D-Day occurred two months later, David sat down with the old veteran, shared some of the finest cognac with him and interviewed him on video tape, getting the full account for his grandchildren’s sake.

Even in 1984, Ramirez never mentioned any of the medals he earned. In his final years, he would repeatedly tell his wife, the former Angela Isabel Herrera-Flores, “Don’t worry about where to bury me. I am entitled to be buried in a veteran’s cemetery.”

When Ramirez died March 21, 1989, Angela submitted his discharge papers, in accordance with his wishes. The funeral home had some doubts since Ramirez wasn’t a “lifer”; however, California Senator Alan Cranston responded by forwarding an official response from the Department of Defense listing all of the medals Ramirez had earned. The Veterans Administration also responded, and Staff Sergeant Adolfo Roberto “ Rusty” Ramirez was buried with full military honors at Riverside National Cemetery, near March Air Force Base in Riverside, Calif., with a 21-gun salute and a fly-over by F-16s in the Missing Man Formation.

JJ Velasquez contributed to this story.

Mr. Ramirez was interviewed in Camarillo, California, in 1984 by his son, David M. Ramirez.