By Connor Higgins

Agusti¬n Louis Hernandez's life has been one of service: to his country as an engineer/gunner on a B-24, to his community as a firefighter and lawman for 37 years, and to his family as a husband and father.

And as a retiree in Houston at the age of 81, he still struggles today with what is right and what is wrong in war and how it squares with his religious beliefs.

Hernandez was born in Houston on Aug. 28, 1924, to Jose and Josefina Hernandez. His mother wanted to name him Louis, but the doctor, also named Agusti¬n, registered his full name as Agusti¬n Louis Hernandez because his birth coincided with San Agustin's Day. He was called Louis throughout his childhood, and it wasn’t until enlisting in the Air Force in 1942 that he discovered his real first name.

His parents were both natives of Valle de Santiago, Guanajuato, Mexico. When they immigrated to the United States, the only requirements for entering the country were a passport and 5-cent fee.

Hernandez’s father, a watchmaker, worked in one of the biggest jewelry stores in Houston.

"We were poor, but we weren't in misery," Hernandez said. "He gave us all the food we wanted and all that he could afford as far as a home was concerned."

Hernandez and his siblings Alfred, Hope and Amelia attended the all-Latino Jones Elementary School and didn't run into many problems. But his junior high school was racially mixed, and Hernandez recalls many occasions when Anglos would pick a fight and he had no choice but to defend himself.

But he also has happy memories of childhood: he and his father fishing in Clear Lake, the family visiting relatives in Mexico, helping his mother plant tomatoes and radishes between her rows of flowers.

It wasn't until six months after the attack on Pearl Harbor that Hernandez, a student at Sam Houston High School, decided to join the military. However, because he was only 17 years old, he needed his father's consent. His father at first refused, but finally gave in after Hernandez persuaded him. The rationale: Enlisting would give Hernandez more of a choice in where he’d be assigned.

But events didn't unfold the way they’d planned. After enlisting in Houston on Nov. 6, 1942, Hernandez went to basic training at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio and then was bounced around the country before being sent to Salt Lake City to become an engineer/gunner, part of a 10-man crew with the 451st Squadron of the 15th Air Force. His crew trained on a B-24, a heavy bomber, in Colorado Springs, Colo.

The 15th Air Force was activated on Nov. 1, 1943. Its operations started the following day and continued throughout Europe until the end of the war.

Eventually, Hernandez was assigned a tour of duty in Foggio, Italy, where he flew 50 missions and made raids in Yugoslavia, Romania, Bulgaria, France and Germany.

At one point during his missions, Hernandez flew for 22 straight days. After the tour was completed, he was sent to Naples to board a ship heading home. Every member of his crew survived, something Hernandez attributes to readiness.

"Flying, it's always a close call," he said. "You're always hit by flak, you're always hit by fighters, you always had bullet holes through everything. It's just God's grace that you made it back to your base, that's all it amounted to."

Released with the rank of staff sergeant on Oct. 15, 1945, Hernandez brought home a Good Conduct Medal, an Air Medal, five combat stars and a Presidential Citation.

He went back to work in Houston for his father as a watchmaker, opening his own shop. But it was a short-lived business venture, and soon he was back in public service -- this time as a fireman.

As one of the first Hispanics in the Houston Fire Department, Hernandez was assigned to the No. 9 Fire Station, where he says he encountered discrimination. He recalls that on his very first day at No. 9, he called in late for work, as his wife, Connie, was giving birth to the couple's third child. When he arrived at the station, he offered cigars to his new co-workers. A few accepted, but most wouldn’t take the cigars, presumably because they didn’t want to be friendly with the only Latino at the station. They often refused to acknowledge him as one of the team, he says, and sometimes he was challenged to fights behind the firehouse.

But as time went on, they "started breaking down," Hernandez said.

He worked for the fire department for 11 years, retiring after being injured while on duty. At that time, firefighters would stand on the side of the truck and hang on to a rail en route to a fire. On that day, it had been raining, and Hernandez slipped off the running board. The truck struck him, breaking his leg.

But his career in public service still was far from over: Hernandez joined the Harris County Sheriff's Department, where he worked for 26 years. He was the first Hispanic to retire from the department with the rank of Sergeant.

Although he’s comfortable discussing the events of his life, he says he still grapples with his role in the war.

"I've had the misfortune of being in the service and killing people," Hernandez said. "Some ... you kill with a weapon, a machine gun, some, you kill by bombs. You still killed them."

"I know I've asked priests about this, and they tell me that in war, it's permissible,'' he said. "I said, 'But the commandment don't say in war it's permissible. All it says is thou shall not kill. Period.’

"Now I was talking to one of my cousins ... and he said, 'Well, you were an instrument for the government to pulling the trigger,'" Hernandez said. "I said, 'Well, that may be, but it's still you killed them. The end result is you killed them.'"

If people discard the "I am better than you, I have more than you" mentality, said Hernandez, then the youth of today won’t have to live through the same experiences of his generation.

"Peace is the whole key to this thing. If you can have peace, you won't have the wars," he said.

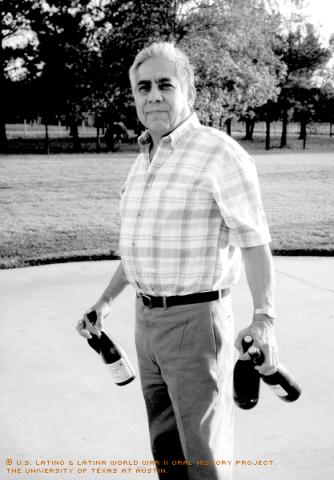

Hernandez and his wife, Canuta Muñoz Hernandez, have three children -- Rebecca, Joseph and Martha -- and two grandchildren. He still loves to fish and enjoys making his own wine, from grapes and other fruit, and he bottles his own private reserve. Life, he says, has been good. But despite all this, he has one nagging aggravation:

"I tell my brother I have nothing but one regret in my whole life," Hernandez said. "And that is that I never learned how to swim."

Mr. Hernandez was interviewed in Houston, Texas, on February 24, 2003, by Ernest Eguia and Paul R. Zepeda.