Alberto Lara Rojo heard about the bombing of Pearl Harbor the day after it happened.

“We didn’t know about it; we lived on the wrong side of town,” recalled the Mexican-American Navy veteran.

On that Monday, the Sunday attack on the American naval base in Hawaii was the talk of his high school in Marfa, Texas, where he was a freshman. Outside the school, other Mexican-American students told him, "It’s a gringo war. It does not affect us Spanish people."

His father, Ruperto Rojo, an Army veteran of World War I who had fought in Germany with the 3rd Artillery, thought otherwise. He encouraged Rojo and his three older brothers to serve their country and also discouraged a neighbor who lived across the creek from moving his family to Mexico so his sons would not be drafted.

For the younger Rojo, the call to serve came in early 1944; his three older brothers, all members of the Civilian Conservation Corps, had been drafted nearer the start of the U.S. entry into World War II. Rojo joined the Navy at the age of 17, inducted on March 25, 1944. After a couple of other jobs, he was assigned to be a storekeeper.

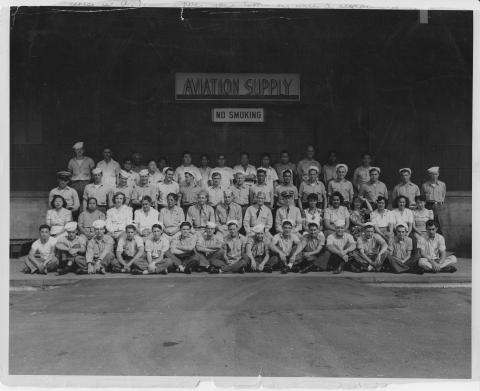

“Finally, they made me an aviation storekeeper,” he added. He served on Midway Island, on the battleship USS New York.

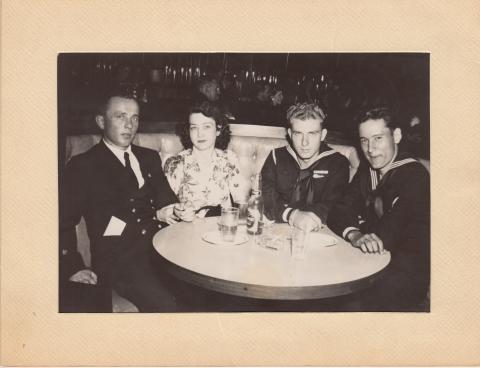

In his earliest days of service, he felt himself to be a Mexican used to proving himself to “Anglos.” Eventually, “out there in the middle of the ocean,” he found he was mostly among non-Mexican sailors from the Eastern regions of America –- places such as Virginia and Brooklyn -– as well as from California. He made a concentrated effort to learn to speak English and even sought French lessons from a priest stationed on the ship. And he made some friendships that lasted decades.

One friendship grew out of a training exercise that could have ended in tragedy. A sailor slipped under a wooden raft and would have drowned if Rojo had not pulled him up. They were trained to use their trousers as flotation devices, Rojo explained, and he said that the two kept in touch but “he’s not here in this world anymore.”

Rojo served most of his war years “2,000 miles away from home” -- from Pearl Harbor, Kaneohe Bay, Wake Island, to Saipan and the Midway Atoll, which Rojo described as “the half difference between America’s West Coast and Japan.”

He recalled the three shifts common to life at sea — eight hours on, eight hours off and eight hours on again. “Midnight to 8 o’clock was the graveyard shift,” he added.

Rojo was not in any battles, but he remembered the time the ship he was on was hit by enemy fire. “A kamikaze hit one of the airplanes on top. I was eight floors below.” During his 27 months of active duty, he “never did get a furlough.” His only contact with family was by mail, and he remembered getting a letter “every three or four months.” Still, he often wonders “why I didn’t stay in.”

He added, “The fear was always there. You never knew what would happen.” Like his father, his older brothers and his second son, Daniel, Rojo learned survival skills. “The military teaches you mostly how to kill or be killed,” he said. Still, he added, he would have been a different person if he had not served during the war.

He was honorably discharged on June 6, 1946, in San Pedro, California, with the rating of storekeeper (V), third class.

Having seen other parts of the world, Rojo returned to his hometown and started to change his world. First, he earned a high school diploma, an achievement his father encouraged. That took Rojo a year and half, and he got credit for his military skills.

Rojo said he had been “born in the wrong era, at a time when discrimination against Mexican Americans ran rampant.”

His hometown was so segregated that there were separate schools for children of Anglo heritage, Latino heritage and African-American heritage. His initial weeks in the Navy were no different, and he recalled crying during those first nights away from his close-knit family.

Born Jan. 6, 1926, he was one of 11 children in a family of five sons and six daughters. His mother, Marcela Lada, was born in Mexico and widowed when her first husband was killed in a village raided by Pancho Villa.

“He claimed to be a Robin Hood,” Rojo said of the legendary Mexican.

Rojo’s father was the child of a woman who never married. “They raised each other,” he said, adding that his paternal grandmother taught him to read from her Bible.

“Families were pretty close in those days; they didn’t know much else,” Rojo said. His father supported the family by working for ranchers and also in construction, doing masonry and carpentry jobs, and he taught his children carpentry skills. Rojo’s mother added to the family income by working as a housekeeper for various families. She also made tortillas, which Rojo would go out and sell for 10 cents a dozen after he came home from school. In those Depression-era days, workers could earn as little as 25 cents to a dollar a day, he noted. Base pay in the Armed Forces when he entered the war was $21 a month.

He met his wife, Margaret Hartnett Rojo, after his return from service and they married Nov. 28, 1948.

“I’d lived in same town as my wife” but they first became acquainted “selling tickets at a movie theater. … We fell in love and have been together for 65 years,” he said during his interview in September 2013.

The couple had three children: Patricia Ann, a teacher; Alberto, a retired U.S. Postal Service employee; and Daniel, a welfare referee and veteran of the Vietnam War. Rojo first supported his family by working at an automobile dealership. As the Navy tests suggested, Rojo was “a good bookkeeper.” But, he said, the dealership was “not paying good money” and friend suggested he could “double and triple” his income by selling insurance in Alpine, 26 miles east.

“I got an offer to sell insurance for more pay. I was raising a family, and I needed the money,” he recalled.

At first, he found barriers and prejudice but persisted and became quite successful.

Rojo, a Democrat, had always been one to get involved. Even when he was in high school, he was teaching Sunday school at the San Pablo Methodist Church in Marfa. He converted to Catholicism, which was his wife’s religion, and became involved in church affairs, serving as a lector, as a choir member, and as a Cursillo rector and director. He was active in the local Veterans of Foreign Wars and American Legion posts and in the Lions and Rotary clubs. And he was a public servant, holding posts as a city councilman, a Presidio County Commissioner and president of the Alpine Community Center.

Although he never served on the school board, he became part of a movement to end discrimination in the school district his children attended. Rojo and the group to which he belonged sat planning strategies at an old café “at 1 or 2 in the morning” and traveled to the state capital to campaign for integrating the schools. Eventually, the group succeeded.

Rojo credits much of what he accomplished in his life to his experiences in the Navy.

“We came back victorious,” he said. “We set an example and dominated the world. There was a lot of pride instilled in everybody that came back healthy. We had new ideas on how to get along.”

Rojo was interviewed by Maggie Rivas-Rodriguez in Alpine, Texas, on July 8, 2013.