By Cheryl Smith Kemp

When Alejandro P. Garza got called up for the war, he was working in a Houston shipyard as a welder. Garza was 18, and, the year before, had dropped out of A.C. Jones High School in his hometown of Beeville, Texas, to help his family out.

“We were dirt poor. … My dad worked day and night to support us. It was very hard for him because he was sick. He suffered from ulcers. … He still managed to feed us and keep us relatively comfortable, but it was a very hard life at that time,” said Garza of growing up in South Texas with his parents and seven siblings.

Garza reported with his draft papers to Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas, on Nov. 14, 1945. He bounced from there to Wichita Falls, Texas, for Basic Training at Sheppard Field, which had opened in 1941 as an Army Air Corps training center.

About three months later, the leaders at Sheppard announced the United States government had decided to make the Air Corps a separate branch of the Armed Forces, and that Garza and everyone else with whom he was training were going to be discharged from the Corps and sworn into the Army Air Forces. Just like that, they were all made members of the Air Forces on Feb. 27, 1946.

“Who knows what the government’s thinking,” said

Garza when asked over the telephone after his interview if he knew why they were all transferred. … “Everything remained the same. We just continued on like nothing else. Just like taking a shower, that’s it.”

Once he completed Basic Training, Garza went to

Chanute Field in Illinois for five or six months of weather-observer training, where he says he learned how to compile weather reports, plot weather maps and send out reports across the globe via teletype machines.

“It was all study. It was just like being in Basic Training … we couldn’t leave camp,” Garza said. “I liked to go to town … [because] at that time, all the guys were in the service and there were only girls in school.”

By the time Garza graduated, the war had ended, but the Army sent him to the island of Luzon in the Philippines anyway, where he began a 16-month stint in the weather service.

“A weather observer is an aid to the Weather Forecaster[.] [A]t that time we would have two or three Forecasters and ten or more weather observers[.] The observers would take the weather readings at our station together with information coming in on the teletype and plot it on the weather maps for the forecaster to read and interpret it, pass it on the pilots before taking off,” Garza wrote.

His job was of particular significance to U.S. aviation operations.

“Weather is very important, especially for the flyers, because they want to know what kind of weather they’re gonna be running into,” explained Garza during his interview. “All in all, we did a great service for the Air Force, [because] we kept them informed of what was going on and what to expect.”

After getting transferred to an air base in Bangkok, Siam (now Thailand), then back to Luzon and, finally, to Okinawa, Japan, where he was stationed about a year, Garza was discharged from the Army Air Forces at the rank of Sergeant on September 10, 1947. Although he returned to the same old Beeville, he was different.

“When we got back, we had gotten a taste of what the outside world was like and how others lived,” said Garza of being a World War II veteran of Mexican-American descent.

As a result, the status quo wouldn’t do: Garza and countless other Chicano veterans in South Texas wanted to be treated as equals to Anglos, like they’d largely been treated in the military. So, in addition to working in the house-moving business with his father, Alejandro Garza, Garza got involved in the Chicano civil rights movement. He says he was significantly influenced by Dr. Hector P. Garcia, who, among other civil-rights related accomplishments, started the American GI Forum, which, according to its website, www.agifusa.com, has become “the largest Federally Chartered Hispanic Veterans organization in the United States[,] with Chapters in 40 states and Puerto Rico. (For more about Hector P Garcia, please see www.utmb.edu/drgarcia/default.htm.)

Garza explained in writing after his interview how he got involved in the movement:

“I happened to go to Corpus Christi, Texas, with a friend[;] he went to see Dr. Hector Garcia. [W]hile at the Dr’s office, the Doctor asked me if I was interested in joining a Veterans Club (American GI Forum) he was organizing. I said I might. So he gave me a long explanation, and I decided to help him get a Chapter started in Beeville[.]

“[S]o he loaded me up with information material to pass out to other Vets in the Beeville Area.”

Along with WWII vet and future Beeville-area mailman Avelardo Garcia, Garza worked to spread the GI Forum’s motto, “Education is our Freedom and Freedom Should be Everybody’s Business,” by working as a recruiter.

“As soon as we had a good number of vets signed up, we called Dr. Hector Garcia and he came and conducted the first organizational meeting[,] signing up a good number of men,” Garza wrote.

And their effort eventually paid off.

“Things began to change and being more advantageous for the Mexican American than it was before,” said Garza, whose career progressed over the years from house-moving to owning grocery store A. Garza Grocery, to running an insurance agency and real estate service.

Before WWII’s end, “local businesses would not hire Hispanics as store clerks; Gas Service Stations would not have a Hispanic attendant. Oil field Companies, SW Bell Telephone and Central Power and Light Co. would not hire Hispanics. Jobs for Hispanics were restricted mostly to farm labors,” Garza wrote.

As a result, his family’s standard of living has been higher than his was as a boy.

“I had better income than what we had when I was growing up,” said Garza, who, along with his wife, Estefana Rodriguez Garza, has raised a daughter and a son in the Beeville area.

“I just can’t emphasize education enough. I think that’s the medium that we can use to better ourselves. There’s nothing else to compare to that,” said Garza, when asked if he has any words of wisdom for young Latinos today. “Go to school and get an education.”

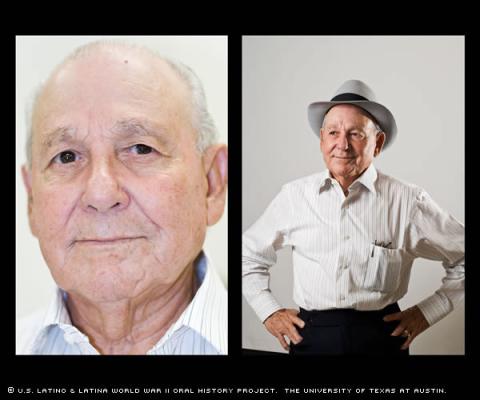

Mr. Garza was interviewed in Beeville Texas, on January 10, 2009, by Martin Montez.