By Soren Silkenson

When Alfred P. Flores was 16, his brother Robert, was lost in an early guided missile attack that sank his ship, the Rohna, three miles off the coast of Italy.

The sinking in the Mediterranean of the British troop transport vessel on Nov. 26, 1943, killed more than 1,000 U.S. troops in one of the worst losses of U.S. maritime history.

Details of the disaster were initially shrouded in military secrecy. Flores was determined to help find his brother but was told he was too young to enlist. Shortly after turning 17, he was finally allowed.

Flores enlisted on April 28, 1944, and reported to Camp Robinson in Arkansas for his basic training. He then joined the paratroopers because he thought it would get him closer to his brother. He attended jump school at Fort Benning, Ga., before heading to England aboard the Queen Elizabeth as a member of the 17th Airborne Division. Flores remembered that the ship zigzagged across the ocean to avoid enemy submarines.

His unit took a train to the coast of France, where he and the rest of the GIs continued training. They were preparing to drop across the Rhine River, which, according to the World War II Multimedia Database (www.worldwar2database.com), Hitler viewed as a symbol of German resolve because no invading army had crossed it in 140 years, since Napoleon in 1805.

Flores said his unit had a 12-foot by 12-foot map made of sand. The map, often called a "sand table," had objects representing all the places over which the GIs were going to jump; it had all the buildings and highways marked.

The jump was part of an Allied air assault known as Operation Varsity, which took place on March 24, 1945. According to his discharge paper, Flores was "first scout leading squad into combat."

Flores recalled that, after parachuting and landing, he found himself in front of a small house near three German tanks. As bullets hit the ground around him, he said he decided to stay still, hoping the enemy would think he was dead. Soon after, Flores saw a sniper and took aim.

"He was coming out of the house in front of us. He must have aimed at me at the same time, because his bullet hit me in the hand, right finger, and into my mouth and into my chest. That was the end of my war," Flores said, adding that he thought he would die.

"I never miss," Flores replied when asked if he had hit the German soldier who shot him.

He recalled sitting on the ground for what seemed like several hours, only able to watch the action around him. He saw a British glider land to drop troops, but one of the German tanks fired into the glider as soon as its hatch opened.

Later, a German man in civilian clothes ran toward him, possibly in an attempt to steal his gun. Flores was unable to handle his gun. But he managed to pull his dagger from his boot and scare the man away. He said the man acted as if he had seen a ghost.

During a break in the fighting, Flores said he saw a couple of feet headed toward a shack. He was able to reach the small shack about 150 yards away by using his elbows to carry his weight. He had lost his helmet, which would have identified him, so he was shot at by his fellow soldiers. Two medics and a chaplain were inside the shack.

Even with three wounds, Flores recalled asking to be fixed up and sent back out to fight, but the medics denied his request. The chaplain gave Flores his last rites, and Flores was placed in a wheelbarrow outside the shack to make room for other soldiers. But he was later told that the look in his eye made some of the medics believe he would survive.

He also later learned that one of the medics who helped him belonged to his hometown church.

The day after Flores received his last rites, he was picked up and sent to a hospital in Bristol, England. While there, his brother George visited him. Flores recalled being able to put on his uniform and the two of them taking a picture together before Alfred was shipped back to the U.S.

He spent the next 10 months recovering in a hospital in El Paso, Texas. He recalled that one of the men he assisted and befriended while recuperating was named Mike Machado, who went on to become a prominent judge.

Flores was discharged as private first class on Jan. 11, 1946. For his service, he earned the Purple Heart, a bronze star and a Combat Infantryman's badge. He also earned a Sharpshooter medal and his paratrooper's wings.

Upon his return to San Antonio, Flores tried to attend college with the help of the GI Bill, but he eventually decided to continue serving his country by working in the civil service at Kelly Air Force Base, on the southwestern edge of San Antonio. (The base, once the largest single employer in San Antonio, was closed in 2001.

He spent 20 years as a wing/fuselage repairman, then the next 15 years investigating plane crashes.

Flores said he mostly looked at T38 fighter planes used for training. He recalled that sometimes better-educated engineers often sought his advice, because his experience enabled him to find the sources of tricky problems. Flores was born on Jan. 30, 1926, in San Antonio and grew up with eight brothers and four sisters. The four eldest boys served in World War II, and his siblings who were too young to enlist aided the war effort by collecting scrap metal.

Flores' father was a carpenter who later worked in the civil service, and his mother was a housewife. He remembered her doing everything for him and his siblings, even making their clothes.

He also remembered her being determined that all her children go to school.

"She wouldn't let you goof off from school. She had a stack of perfect attendance certificates from all of the family, even though it was sometimes hard," Flores said.

He attended the same church as his wife, Olga, when they were children, but she was younger, and he said he did not notice her then.

"After the war, she sprung up a little bit ... So we went and got married," he said.

At the time of his interview, they had been together more than 60 years and had three children, two daughters and a son. They also had seven grandchildren and 12 great grandchildren.

Flores spent his time hunting, fishing and visiting with his grandchildren. In fact, he taught all of the boys in his family to hunt and fish.

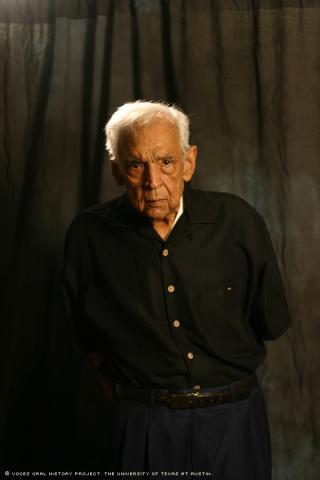

Mr. Flores was interviewed by Jenny Achilles in San Antonio on Aug. 4, 2007.