By Brigit Benestante

Growing up in the 1950s and 1960s, Alfredo Santos was ashamed of his ethnicity.

“I didn’t like being a Mexican,” he said. “I was embarrassed, I guess, to be a Mexican.”

His transformation began in 1968, when he joined the Mexican American Youth Organization, which discussed issues in the Hispanic community in Uvalde, the Texas town where he lived. It flowered when he participated in a 1970 walkout at Uvalde High School to protest discrimination against Hispanic students and the dismissal of a Hispanic teacher. The experience changed him and altered the course of his life.

Santos was born to John and Molly Santos on May 15, 1952, in Stockton, Calif. After John Santos died in 1958, Alfredo lived with his mother and two siblings for a short time in Uvalde, his father's hometown. He later moved back to Stockton to live with his grandparents.

In Stockton, Santos said he did not want to call attention to his race during school. “I was struggling with my identity as a fourth-grader, fifth-grader,” he said. “I was as brown as I am today. I don’t know who the hell I was trying to hide from. Myself, I guess.”

When he was in the eighth grade, Santos moved back to Uvalde, about 85 miles west of San Antonio. There, Santos found himself caught between two social worlds -- he was Mexican American but spoke almost no Spanish. He spent his first year in Uvalde speaking only to his cousins.

“The Mexican kids wouldn’t talk to me because I didn’t really speak Spanish,” Santos said. “The Anglo kids wouldn’t really talk to me because I was Mexican.”

In high school, Santos joined the football team, where he made friends and picked up street Spanish. He began to notice the differences in the way Mexican-American students were treated. According to Santos, school officials sorted freshmen into college and non-college tracks. Santos and most of the Mexican-American students were put on the non-college track.

“I think some teachers tried to treat us the same, but I don’t think their expectations for us were the same,” Santos said. “I think they tolerated us, tolerated me and my friends. I never had a conversation with a teacher on where to go to college or how to go to college, or anything like that.”

Santos did not do well academically his freshman or sophomore years, and he dropped out in 1969, in the middle of his junior year. Although he was not succeeding in school, he became very active in social and political movements outside of the classroom. He attended weekly Mexican American Youth Organization meetings, where he heard older students speak about local issues. He became involved in political campaigns surrounding the Chicano movement.

And he began a journey of self-discovery.

“When the Chicano movement started, I then started to grasp for a better understanding of who I was,” he said.

Santos' activism extended beyond Uvalde. In November of 1969, he and his friends cut class in order to participate in the Crystal City school walkout, 40 miles to the south. Crystal City students shared the frustrations that Uvalde students had; among many issues, Mexican-American residents wanted to see more diversity among teachers and wanted to lift the ban on speaking Spanish in school.

Shortly after, on April 13, 1970, Uvalde experienced a resistance of its own. Santos was cruising around in elementary school teacher, was under review at the school board meeting. Garza had irritated school officials by advocating for Mexican-American parents. That especially did not sit well with the school principal.

Santos turned onto Getty Street, where the meeting was being held , and went inside.

“It was packed, body to body,” he said.

Fifteen minutes later, Garza was denied a hearing on his contract renewal. Immediately following the meeting, everyone gathered on the sidewalk where Garza and his attorney explained what had transpired.

In a separate interview, Garza said his contract renewal was denied because he had started working toward a master’s degree at Texas State University, and the principal felt threatened that Garza would attempt to take his job. Additionally, Garza said his recent run for county judge had angered school board members.

Outside the meeting, Jesse Gamez, Garza’s attorney, said, “If I were from Uvalde, I wouldn’t let them treat me like this,” Santos recalled.

“There was a pause ... a silence,” Santos said. “Then Gilbert Torres said, ‘Well, I’m not going to send my kids to school until George Garza’s contract is resolved.’ And then somebody yelled, ‘Walkout!’ Somebody else added, ‘Walkout!’ And then everybody was saying it. The walkout idea was planted.”

That night, Santos and other community members made picket signs and formed a plan. The next morning, the walkout began. Santos said the walkout was not just about Garza; it was about a number of discrimination issues that Mexican-American citizens in Uvalde faced.

“The walkout was really a manifestation of a lot of issues that had been building and boiling over the years,” Santos said. “The people said no to discrimination, no to poor education, no to a lot of the bad things that had been going on.

"The walkout shocked a lot of people. The walkout made a lot of us very proud. You know, finally somebody had stood up and said something and did something. Somebody had to go first. And it just so happened, it was us," he said.

During second period, students stood up and walked out. As the walkout continued, students drafted a list of demands that included more Mexican-American teachers and inclusive textbooks. The school board rejected the list and demanded that the students go back to school.

Over the next six weeks, as he became active in the walkout, Santos began to see himself differently. “I was starting to like myself as a Chicano,” he said.

“I would get up early. I was excited,” Santos said. “I would go to the church to see if there was anything for me to do. Then we had the huelga (strike) schools, and would attend sessions and listen to a lot of guest speakers. Then around 3 o’clock, we’d go to whatever school was chosen and would do a picket line and march around the school.”

As outsiders arrived to support the walkout, Santos used his van to give them tours of the town. He delivered food and students to the makeshift school at a local church. He attended rallies across Texas in support of rights for Mexican-Americans, drawing inspiration from the speakers.

“We were doing a lot of movement stuff that I had never done before," he said. "Meeting lots of people -- older people, college people, people who were smarter than me. I liked all of that.” he said. “I liked that they were standing up, that they had courage. They spoke very well. I did not speak very well back then. But I was learning as fast as I could.”

According to Santos, on some days, more than 600 students, including middleschoolers, would march in picket lines. A local farm labor contractor supplied trucks to take hundreds of students to the picket lines. Law enforcement was always present during the protests.

“There was a big police presence,” Santos said. “They had helicopters. They had snipers on the roofs of buildings. I wasn’t intimidated.”

Not all Mexican-American families supported the walkout. Santos said many students did not participate because their parents would not allow it. Other students thought the walkout was too radical. One day, Santos used his van as a “symbolic hearse,” with a makeshift coffin representing students who did not participate.

“We symbolically sent them to hell at a rally in the park,” Santos said. “It made my mother furious.”

After six weeks, the walkout ended. Unfortunately for the participants, the school district refused to comply with their demands and required any students who had participated to repeat the school year. Many seniors were not able to graduate, including many of the Honor Society students. Santos said the walkout nonetheless had a huge impact on his life.

“Me and my buddies, we were football players and later we were academic screw-ups,” he said. “The walkout made a lot of us very proud ... Even though we didn’t win, the walkout changed us. A lot of us went on to do a lot of bigger and better things.”

The walkout was the beginning of a lifetime of activism for Santos. After the walkout, he moved back to California and attended San Joaquin Delta College for two years before transferring to the University of California, Berkeley. There, he continued to be involved with social movements, particularly the United Farm Workers.

After graduating from Berkeley, he became a labor organizer for Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers. He noticed a lot of similarities between the issues that Mexican-Americans felt in California and in Uvalde.

“I gained a whole wealth of knowledge,” he said. “My intellectual world just opened up, and we filled it with all kinds of knowledge. I became a much more astute person, I think. A better public speaker. I learned how to play guitar. ... I became a college graduate. I was doing a lot of activist work.”

Santos was becoming a man who was proud to stand in his own skin.

“When I was growing up I was Alfred,” he said. “When I went to California, I reinvented myself and became Alfredo. ... I was very comfortable in my new identity.”

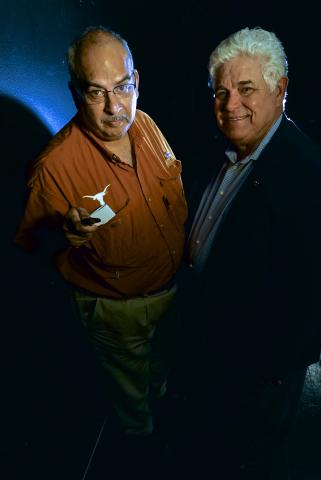

Santos now runs his own political newspaper, La Voz, and is a graduate student at the University of Texas at Austin. He and his wife, Diana, have one daughter, Yleana.

“I’m still all about social justice issues," he said. "I’m about fairness, equality, equity. I’m also more about storytelling. The same principles that I adopted many years ago are still with me today and are still near and dear. They are things that I will stand up for at a moment’s notice if I find they’re being violated."

Mr. Santos was interviewed by Anna Casey in Uvalde, Texas, on April 9, 2016.