By Frank Trejo

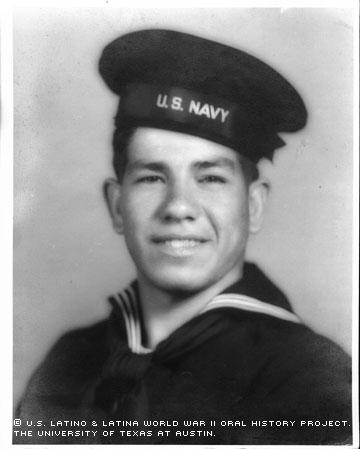

When Antonio F. Moreno stormed ashore Iwo Jima as a U.S. Marine medical corpsman, a familiar odor greeted him.

Moreno, who grew on Texas' Gulf Coast, knew there was no mistaking the smell that wafted up to him as he dug into the earth to prepare a foxhole. The sulfur bubbling under the volcanic island smelled just like the sulfur of his childhood a half a world away.

"It smelled like rotten eggs; that's why it reminded me of home," he said.

Home for Moreno was a company mining town run by a sulfur company. The sulfur was used for medicine, explosives and ammunitions, and the town was kept busy digging into the earth to retrieve it.

The 77-year-old recalled his childhood as a happy time and his adventures in the Pacific during World War II as a time of great discovery.

Moreno's parents were Mexican immigrants from the state of Nuevo Leon. His father, Julio Espinosa Moreno, had worked in the silver mines of his home country. When the family moved to Texas, he worked long hours for the sulfur mining company.

Moreno's mother, Josefita Salazar Marroquìn Moreno, worked as a housewife, taking care of her nine children.

"She only went to the second grade," Moreno said of his mother. "But she had a keen mind. She understood English, even though she couldn't speak it."

Moreno was actually born in a place that is no longer on any map, a mining town called Gulf, in Matagorda County, Texas. It was located about five miles from Bay City.

Years of mining eventually caused the Gulf of Mexico to seep into the earth and reclaim the ground where the town stood, forcing the company to move a few miles down the road and build New Gulf, in Wharton County.

It was when his family moved into Wharton County that Moreno said he first became aware of discrimination against Latinos.

"We were excluded from a lot of things, the band and other activities at school," Moreno said.

For him and his siblings - five brothers and three sisters - schoolwork was one way to escape from discrimination. They studied after milking the cows and tending to the hogs in the mornings and after the school bus dropped them off.

He remembered that his parents stressed education to all their children.

"They were always trying to get us to study, most of the time," Moreno recalled. "And not to squander our time. But of course, kids are kids."

As children, the Moreno kids would sell produce to help bring in money for the family. Items such as melons, corn and raspas (shaved ice) were bought wholesale and then sold for retail prices on the street.

After finishing school in Freeport, Texas, Moreno worked as a busboy at a Dow Chemical Co. cafeteria in Freeport, Texas. Moreno says he was playing touch football when he first heard that the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. Neither he nor most of his friends had any idea where Pearl Harbor was, or the significance of the event.

"It was too far away for us to comprehend," Moreno said.

It was only in the days and weeks that followed that the seriousness of the situation began to dawn on them, as they saw pictures of what had happened. The country was at war, and even the mining town on the Gulf was pitching in. Moreno said his father sometimes worked 22 hours a day, helping produce sulfur for the war effort.

"I started noticing that everything was in more of a hurry because of the war," he said.

The oldest of his siblings, Moreno was 18 when he received his draft notice in 1943. He and nine other boys from his community all went to sign up together.

Moreno initially signed on with the Navy and trained as a pharmacist mate at the San Diego Naval Hospital. Later, at Camp Elliot, he trained to be a corpsman and later joined the 5th Marine Division at Camp Pendleton. He was assigned to the 2d Platoon, Company E, 27th Marine Regiment.

It was with this group that he traveled to Iwo Jima in the South Pacific.

Storming ashore as part of the second wave, loaded with equipment and a rifle, the Marines found it difficult to maneuver. Moreno recalled very slow going for days and weeks at a time. For 16 months, he carried medical supplies and gave emergency first aid to injured Marines. He witnessed a Marines Corps amtrac annihilated by a bomb; the vessel carried 25 Marines, ammunition and supplies. Two men in the platoon - friends of Moreno's - died in battle. Moreno had been unable to render aid because his bulky 75-pound supply pack and constant mortar fire prevented him from arriving in time.

"The volcanic terraces were steep and hard to climb," he later wrote to the Project. "It took me until late afternoon to reach solid ground where I left my supply at a medical station."

The platoon lost another comrade and friend as the men neared the opposite side of the island. Lt. Jack Lummus, a former Baylor University and New York Giants football player, died after stepping on a land mine a few feet away from Moreno.

"I tried all I could (to save him), but his stomach was ruptured and he was losing a lot of blood. He died when we reached the medical battalion," Moreno recalled.

Luck was not always against the group, however. In one battle, a shell from a 16-inch cannon landed in the lap of the platoon. To everyone's amazement, the shell did not explode - it was a dud.

"The good Lord was with us...it came so close." Moreno said.

A small U.S. flag was raised in Iwo Jima on Feb. 23, 1945. Later, a larger flag was sent from a ship to replace it. Moreno said it was a sign that we were on our way to winning the war.

"[Iwo Jima] was an eye-opener for me," he said, adding he had had never before experienced holding a gun.

He was discharged on March 16, 1945, and returned home.

He returned to Texas after the war and eventually met Gloria Helen Gutierrez, who would become his wife.

After the war, Moreno said, things for Latinos improved "by leaps and bounds" back in the States, although he noted that Texas was still a place where discrimination remained.

Moreno earned his Associate's degree from Wharton College in Texas and then attended the University of Texas for a time, studying literature. He worked at Safeway grocery store as a checker and part-time produce manager before working for the U.S. Postal Service. He stayed there for more than 37 years, finally retiring as a claims clerk in 1988.

His wife worked as a teacher for more than 30 years in Austin. They have two children and five grandchildren.

At the time of his interview in 2001, Moreno was active in his church and with his Shrine Temple, Ben Hur. Participation in Shriners and Scottish Rites Masonic groups has been an important element of his life, he said, because of the good they do for the community, the state and the whole country.

He encouraged all Latinos to become involved in groups, especially in organizations that don't necessarily have many minorities in them.

"You need to be more alert to the things happening around you," he said. "Stay in school and educate yourself to enter the fabric of life."

Mr. Moreno was interviewed in Austin, Texas, on December 12, 2001, by Erika Martinez.