By Grant Abston

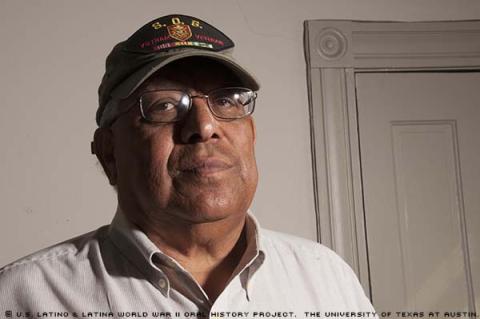

As a sophomore at La Salle High School in San Antonio, Texas, Arturo Ramirez stood out from his classmates.

Ramirez already had a working history that spanned many years. He had worked alongside his father cleaning offices at the Union Stockyards in San Marcos, northeast of San Antonio, since he was eight years old. The work day sometimes began at 4 a.m. before school. He had also worked landscaping for two years before taking a job at a bowling alley on the south side of town during his sophomore year.

“It taught me: Always be very organized and be able to -- before the word was even common -- multi-task,” Ramirez said. “I could do so many things at one time or one right behind the other and not freak out. I never felt stressed. To me, it was relaxing to do the work.”

Although those jobs instilled a strong work ethic in Ramirez, who would go on to lead secret military missions during the Vietnam War era, it was his job at the bowling alley that proved to be the most influential in shaping his views on the military and civil rights.

“There was a lot of military at the south side bowling alley,” Ramirez said. “In a way, it illustrated to me why I didn’t want a military career.

I talked to all those people who were in the military, and most of them were enlisted that went there. These people were mixing it up with the community, and they were all cool. But I knew at that point that I didn’t want that as a career. They were talking to me about anything and everything, and I didn’t want to seem arrogant. But I knew more about the world than they did, and that was just the way it was.”

Ramirez’s broadened world view started after meeting Alejandro, a Cuban-born student who was unhappy about having been removed from his homeland and sent to the United States. The pair became best friends at La Salle High School. Ramirez aided Alejandro in his transition to the United States. He also stood out in being able to effectively communicate with him in Spanish. Ramirez recalled that Alejandro gave him an education he had not yet found in his school courses.

“He assigned me a curriculum of books to read and would ask me questions,” Ramirez said. “It was an amazing education that I got through him. He had me read all the classics – Friedrich Engels, Karl Marx and Leon Trotsky.”

In addition to his ongoing education with Alejandro, the mechanic at the bowling alley had given Ramirez tapes of Malcolm X as he began educating himself on the civil rights movement. Ramirez’s knowledge of the changing landscape throughout the country prompted him to pursue college after graduating from LaSalle High School. However, while studying at San Antonio Community College, his plans took a sharp turn.

Ramirez’s birthday had been assigned draft number 26 in the Selective Service lottery when he received his draft notice. He also realized that his grade point average at San Antonio Community College was not high enough to exempt him from the draft. So Ramirez decided to enlist in the U.S. Air Force in 1966 at the age of 19.

“There was no way I was going to get out of it, so I joined the Air Force to circumvent being a grunt and ultimately ended up backwards,” Ramirez said. “I ended up on the ground and ended up doing stuff that I never thought I would do.” Ramirez underwent basic training at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio before being sent across the country to various technical schools. He was enrolled in the civil engineering program, learning demolition and construction while also attending language school at Indiana University.

After his training, Ramirez sent a letter to his congressman, protesting his overseas assignment. His congressman responded, and the orders were scrapped. But he received temporary duty assignments in the Taiwanese capital, Taipei, and in Japan. While on temporary assignment in Taipei, Ramirez was ordered to join a Studies and Observation Group, a classified military operation that carried out missions during the Vietnam War.

“I was persona non grata,” Ramirez said. “You had no dog tags, you had no U.S. clothes and no U.S. uniform.”

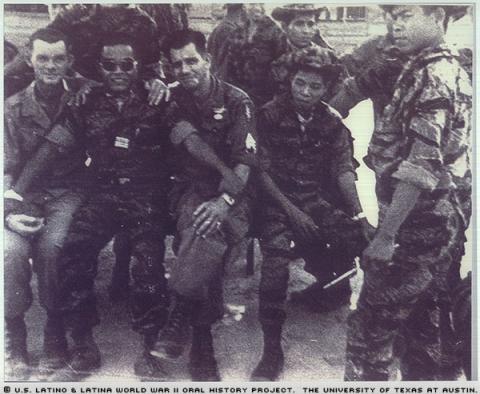

Ramirez was shipped to international waters with the Navy before being picked up by Norwegian contractors who would escort the Studies and Observation Group members on patrol torpedo boats to the various drop points. Once there, Ramirez said that he and two other group leaders were assigned three Nung tribesmen, who would help the group leaders execute the various missions, he said. Of the three group leaders, one served as the superior, assigning missions to each group, he added. Once assignments were handed out, the groups would be gone for six months at a time before reconvening.

“The Pentagon was your handler,” Ramirez said. “Not the Air Force or the Navy or the Army. It came straight from the Pentagon to your superior. You were assigned that duty and then you operated however you could. You were on your own. Once you’re out there, you couldn’t talk to anybody.”

After a year serving on the S.O.G, Ramirez was told he would be returning home after his second six-month check-in. He was shipped back to Taipei before returning to the United States in 1970.

“I celebrated by eating pork fried rice that cost me 20 cents,” Ramirez recalled.

Upon returning, Ramirez quickly became involved in the anti-war movement. He recalled having organized an anti-war protest in San Pedro Park in San Antonio in 1970. He also joined the Vietnam Veterans Against the War and made multiple trips to Washington, D.C., to participate in anti-war demonstrations. He said he served as stage security at one demonstration where John Lennon performed.

In addition to his anti-war activism, Ramirez returned to school immediately. After resuming his studies at San Antonio College, he received a scholarship to go to school in Michigan and attended both Central Michigan University and Wayne State University from 1971 to 1975, before having been admitted to study at the Fitzwilliam College at the University of Cambridge in England in 1983. Ramirez said that he received his master’s degree from Trinity University in 1985 and his doctorate from Texas A&M University in 1990, for which he obtained the Hazlewood Exemption, a state program that provides education benefits to honorably discharged Texas veterans and their dependents.

In addition to his studies, Ramirez said that he had worked for Caterpillar Inc. after returning from the service. He later started his own company in San Antonio. It specialized in environmental cleanup.

His hard feelings towards the military remained. Despite having health complications that he said were due to exposure to Agent Orange, it took Ramirez 34 years to receive disability after since he applied in 1970.

However, Ramirez said that a remedy taught to him by a grandmother of one of the tribesman helped him recover from some of the effects the war has had on him, including post-traumatic stress disorder.

“Cinnamon was one of my saving graces,” Ramirez said. “That old lady would drink [it] all the time. I boil cinnamon until it’s sweet and drink at least a cup or two day. I don’t know what it does, but it changes your outlook and physically you feel better.”

And, although the 60 percent disability coverage he received is less than the 100 percent he feels he deserves, it was progress coming from a military that Ramirez says failed to recognize him and his service in the Vietnam War.

“You can’t be cited or awarded for something that didn’t happen,” Ramirez said, indicating the kind of work he undertook prevented him from being properly recognized for his service.

But Ramirez said his military service did teach him the importance of speaking out for what you believe in.

“Get active in something,” Ramirez said. “Like the old Negro preacher used to say, ‘You got to stand up for something, or you’ll fall for anything.’ That’s essentially what young people, I think, have a responsibility to do today.”

(Mr. Ramirez was interviewed on April 20, 2011, in San Antonio, Texas, by Grant Abston.)