By Clara Obregón

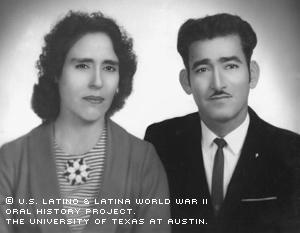

Ascención Ambros Cortez can't help but cry when she thinks of the sacrifices her brother, Enrique Ambros, and husband, Hernan Cortez, Sr., made for their country during World War II. Her husband lost his right hand and her brother paid the ultimate price -- his life. Both gladly volunteered to serve their country, she remembers.

Cortez was one of seven children born to Gaspar and Dominga Ambros in Laredo, Texas. Gaspar died from a head injury after falling off a horse in 1933, leaving Dominga widowed with seven children.

"I was only 7 when I lost my father, and it was very hard," Cortez said.

Her brother, Enrique, became the head of household and spent long hours tending to the family's fields. Later, he enlisted in the Army; his income sustained the family.

"Even though he was at war, he was the one who supported the family," Cortez said.

When her brother was killed, it was like losing a father for a second time, Cortez says. Despite the tragedy, however, she doesn't remember ever lacking food or basic necessities.

"They gave us stamps to buy everything we needed," she said. "There was no shortage of food. We lived on the Rancho Colorado, where onions, tomatoes and other crops were grown. When my father was still alive, he would cross the border to go buy the rest of our groceries on the other side."

Cortez doesn't remember celebrating a lot of holidays, but she did visit the cemetery regularly to take flowers to loved ones. And on a few occasions, she attended dances.

Cortez married Hernan at the age of 15, shortly after she entered the sixth grade. Herman was also an enlisted man in the U.S. Army and was soon shipped out to the Pacific, leaving Cortez pregnant with their first child. She says she moved in with her mother-in-law and became like a daughter to her.

Herman was assigned to be a medic. Cortez wrote to him regularly and remembers receiving letters from Hawaii. One day, he sent her a Bible given to him at an evangelical gathering while on tour.

"My husband was attending evangelical services, simply because they served food. That's where he got the Bible. Back then, I was Catholic," she said. "That's when I started to read the Bible."

Cortez tearfully remembers that her husband came home missing his right hand.

"His job was to give first aid to the wounded. But one day a grenade hit the foxhole where he was tending to an injured man. He picked up the grenade to throw it back, and it exploded in his hand. He gave himself first aid before he lost consciousness," Cortez said.

Cortez says Herman was overcome with grief after losing his appendage and considered suicide.

"He wanted to let himself fall from the second floor of a building because he lost his hand," she said. "The whole thing made him very nervous. But God allowed him to return home."

Cortez was 17 when Herman returned. His first child was 8 months old. At first, simple tasks, like greeting others, were difficult for him, Cortez says; however, he gradually became accustomed to doing everything with one hand.

Cortez says Herman even went to a hospital for rehabilitation in Temple, Texas, where he had to learn how to write, eat and tie his shoes with only his left apendage.

"I remember his hand was wrapped up in bandages and he didn't know what to do when people wanted to shake his hand," she recalled.

Herman also suffered from lingering fears from the war.

"I remember he became anxious at hearing firecrackers go off," she said. "When airplanes flew over, he imagined he was still at war."

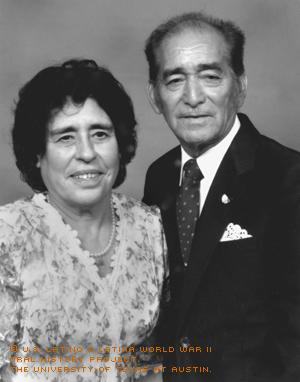

Herman became a police officer for the Laredo Police Department. Later, he became an independent private detective, a notary public and a debt collector, and was involved in a variety of business ventures. He learned to use his left hand so well that he played the organ and even an accordion, which he was forced to turn upside down so he could play the keys. For pleasure he composed songs.

"My dad was very musically inclined," recalled one of his sons, Juan Cortez, in a taped interview. "He would sing songs around the house and he wrote songs. I sing some of those songs sometimes. I'm going to see if I can get some of those songs redone and get some of those songs taped."

Juan says one of his father's best compositions was a song written after President John F. Kennedy's assassination.

Cortez says that, as a woman, she was mostly relegated to her roles as mother of 11 and homemaker, but that she didn’t feel unfairly treated by men. For example, she says Herman didn’t criticize her when she decided to change her religion from Catholicism to another Christian faith. In fact, Cortez says he played the organ during church services and they became missionaries together.

Mrs. Cortez was interviewed in San Antonio, Texas, on October 25, 2003, by Desirée Mata.