By David Muto

Growing up in San Antonio, Texas, Baldomero Estala relied on quiet independence.

In junior high school – from which Estala withdrew for economic reasons before fighting in World War II – he kept to himself, he says.

“I tried to get along with people, and I learned how to read Spanish,” said Estala of his formal education. “I never belonged to a sports team. I wasn’t too much of a mixer with people in school.”

It’s with this same reticence that Estala reflects on the years he spent in the Army and, later, as a prisoner of war in Germany. Estala has difficulty recalling with detail much of his youth and subsequent enlistment, but even as the effects of aging plague the war veteran, memories linger.

Estala, who was born and raised in San Antonio with three sisters and two brothers, spent much of his childhood in his father’s corner store, manning the shop while his father, Ruperto Estala, took breaks. As a child, Estala enjoyed playing soccer and singing; and though his family did rather well financially, his father’s sudden death forced Estala’s mother, Celestine Arriaga Estala, to take over shop-keeping responsibilities and the family’s finances. To help his mother, Estala enlisted in the Civilian Conservation Corps, a popular New Deal relief program that provided manual work for unemployed men. Stationed at a work camp in Long Pine, Calif., he earned $30 a month, keeping $5 for himself and sending the rest home to his mother.

Estala then returned to San Antonio, and was working in the paint department of the local Pontiac car dealership when WWII broke out in 1941. He was drafted July 25, 1942, after which he was called to basic training in Wichita Falls, Texas, and then departed for Sioux Falls, S.D., for radio and mechanics military schooling. According to his son, Roy Estala, he was then sent to Snetterton Heath Army Air Station in England as part of the 337th Bombardment Squadron of the 8th Air Force’s 96th Bombardment Group. Estala worked as a replacement radio operator in the Army Air Corps, filling in on aircraft missions for absent soldiers.

On the morning of May 8, 1944, near Resthausen, Germany, Estala was shot down en route to an attack on Berlin, Germany, said Roy in an e-mail after his father’s interview. Estala ended his 13th mission by bailing out of the Boeing B-17G Flying Fortress in enemy territory.

“It was just, out we went,” Estala said. “Going down [with the parachute], I looked down, and there comes a German with a rifle ready to pick me up.”

Estala was sent to Stalag Luft III, a prisoner-of-war camp in Sagan, Germany (now Zagan, Poland), the first in a series of camps in which he would be interred. A couple of months before Estala was a resident of Stalag III, 200 of the prison’s then-captives had dug it a special place in history:

“Six hundred officer air crew shot down over Europe – American, British, Canadian, Australian, New Zealand, South African, Scandinavian, French, Polish, Czechoslovakian, and half a dozen other nationalities – … had slaved for more than a year, digging three tunnels that were deeper and more complex than any in escape history,” writes Alan Burgess in “The Longest Tunnel.”

On the night of March 24, 1944, the men begin crawling through a lit, more than 300-foot-long tunnel called Harry, “reach the pine trees, the snow, the star-filled sky, and smell the clean air of freedom,” continues Burgess, who notes in the first page of his recounting of the escape that, “Within days most of them were recaptured. … Only three made it to safety.”

Estala dwells on his POW experience only briefly, saying he and his fellow captives were treated rather well.

“No, not really,” responded Estala when asked if he was frightened while in the camps. “I was hungry.”

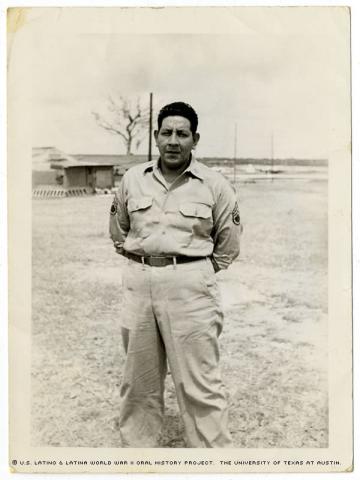

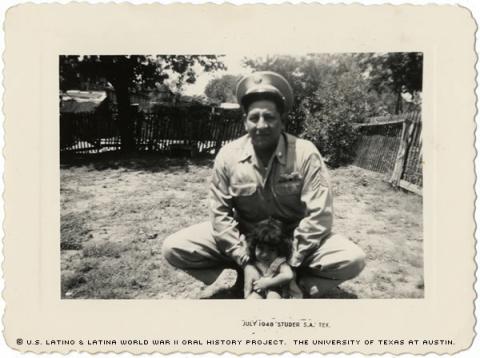

After Patton's Third Army liberated American prisoners from camp Lucky Strike in the Le-Harve, France, area on May 8, 1945, Estala returned to Texas, where he was honorably discharged at the rank of Staff Sergeant, but then stayed on with the armed services in the Air Force until his retirement in 1964 at the rank of Tech Sergeant.

A Post-war boom brought economic prosperity and a newfound way of life to many American citizens. At 28, Estala married Graciela Inclán, who was 19 at the time, and the couple raised two daughters and three sons. When reflecting on their childhood, Estala says he was fortunate enough to be able to offer his children a rather comfortable life.

“I was able to drive them to school, bring them back from school,” he said. “[Take them to] certain restaurants where they sold good hamburgers.”

But Estala is reluctant to acknowledge much in the way of his personal post-war successes.

“Not that I wasn’t very good at whatever I did,” Estala said. “But I think the only thing good I ever learned to do was put radios in the airplanes.”

Downplaying his own personal struggles, restraint also colors Estala’s reflections on race relations during this period. For example, when asked if he ever experienced discrimination, he said “No, never once. [People] sort of looked up to me because I was a prisoner of war.”

With his recollections at times lacking descriptive and emotional detail, Estala said, "I wish I could remember a lot of stuff I knew, but my mind isn't what it used to be."

The influence of war and his love of country is evident, however, when he converses and tells stories, even when he sings. During a quick performance of the “Star-Spangled Banner,” for example, Estala forgets many of the words, but “sometimes [the songs] just come to me,” he said.

Mr. Estala was interviewed in San Antonio, Texas on May 3, 2008, by Cheryl Smith Kemp.