![Vietnam Vet, Ben Saenz, was interviewed in Houston, Texas, on April 9, 2011. [Voces Oral History Project/ Michelle J Lojewski]](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/IMG-895-04-600.jpg?itok=cET8Xz9I)

By Gilbert Song

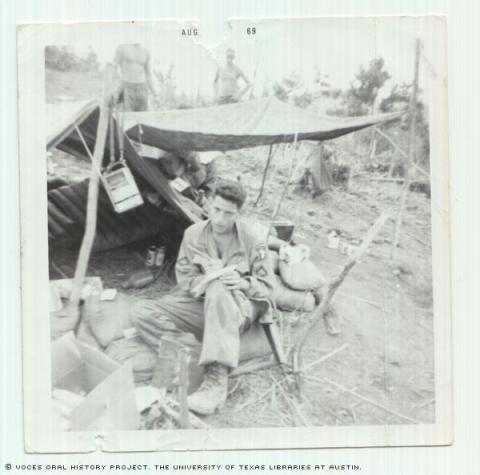

Bernardino "Ben" Saenz Jr. arrived in Vietnam to the sound of sirens and pitch black darkness in May 1969, just five months after he was drafted. The smell was terrible, he recalled.

"I knew I was in the real stuff when I saw the bodies," Saenz said. "That's the worst smell, seeing a dead body that had been there months decaying. I remember pulling the arm of one and I got maggots all over me." Enemy graves had to be dug up to see if weapons or food were buried under them, he added.

These kinds of experiences transformed Saenz, who said that he had been a popular, athletic youth, into a battle-tested paratrooper. But he also acknowledged having become an emotional casualty of war, afflicted with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

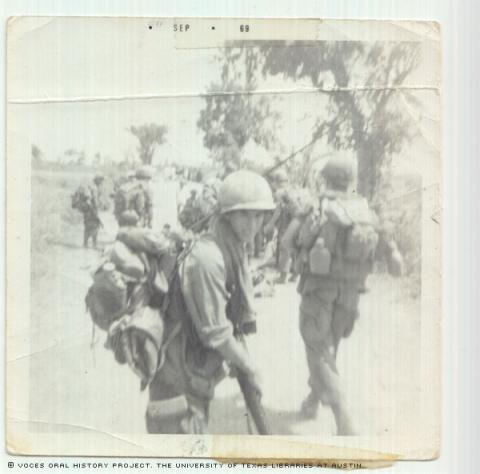

Upon landing in South Vietnam, he was assigned to the storied 1st Battalion, 501st Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division. During the Vietnam War, the battalion operated primarily in the A Shau Valley, which U.S. forces nicknamed the "Valley of Death." The valley, which ran along part of the border between South Vietnam and Laos, served the communist Viet Cong guerillas as a key infiltration point to the South. It was also the site of the watershed Battle of Hamburger Hill, a 10-day clash with North Vietnamese forces in May 1969. The U.S. and South Vietnamese Army took the hill through a frontal assault, but the battle may have contributed to President Nixon's announcement of the first U.S. troop withdrawals from South Vietnam.

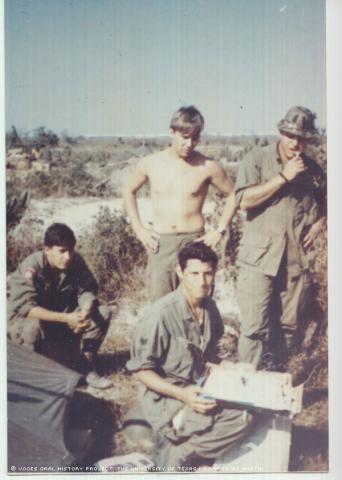

There were so many casualties in the A Shau Valley region that replacement soldiers arrived frequently, Saenz remembered.

"Day to day, you didn't know if you were going to live or die" he said. "You hardly ever saw any of the enemy. You knew they were there because they were shooting at you. After the firefight, we would go out there and see blood trails. That's what a grunt's life was."

Saenz recalled a particular attack in which only 10 men from a single company survived.

"We had climbed a mountain that day...and found some bunkers," he said. "[My captain] said, 'We're going to stay here for the night.' I said, 'No sir, we can't stay here because the [enemies] know our position.' "

The commanding officer ignored his warning and refused to move the company a safe distance away from the bunkers, according to Saenz. Later, in pitch black darkness, the Viet Cong mortars rained down upon them.

"You couldn't see your hand in front of you," Saenz said. "It was exploding all around us, and you couldn't do anything. Guys were yelling and crying 'Medic! Medic!' and guys were getting killed."

When daylight finally broke, Saenz saw the lifeless bodies of his fellow soldiers all around.

"I told you! I told you we should've left here!" Saenz remembered screaming at his captain.

Saenz was shot in the left shoulder and suffered shrapnel wounds. He was sent back to base to recover. He got drunk on the nearby beach, which was the usual routine after a rough time in the field. He and the few others who survived the attack drank and cried together to try and forget the pain. But Saenz couldn't forget.

"I can still see their faces, when they were shot, when they cried, when they were in pain," he said. "I had guys die in my arms telling me to tell them they were good soldiers."

Another time, during a search and destroy mission, a close friend of Saenz stepped on a land mine. The explosion killed the friend instantly and blew Saenz 50 feet in the air. Saenz survived, but he suffered a temporary loss of hearing and speech.

His platoon mates thought that he was dead, since he was unresponsive and covered in blood. It took a few minutes for his fellow soldiers to understand that Saenz was only stunned and covered in the fellow soldier's blood, rather than his own.

"The birds starting coming and eating the flesh" remaining from his friend, Saenz recalled. "So, we started shooting the birds... to this day I still remember that."

Eventually, Saenz left Vietnam and returned to his hometown of Houston. He remembered being greeted by anti-war protestors at the airport. They called him "baby killer" and threw eggs at him. They told him he should have died in Vietnam.

"I couldn't understand that," said Saenz. "I considered myself a hero. I mean, how dare they?"

After his dispiriting welcome home and horrific battlefield experiences, the emotional and psychological trauma began to take its toll. To cope, he drank just as he did on the beach in Vietnam.

"Every time I would have a problem, I would drink and drink and drink," he recalled. "When I came back from Vietnam, I was an alcoholic. I came back really, really bad. I wasn't the same person."

Saenz lashed out against his family, as well. He made his younger brothers pull guard duty at night. He even threatened to cut their throats if they fell asleep.

This was uncharacteristic of the loving son who sent the majority of his Army paychecks home to support his family, which also included his mother and father, five older sisters and those two younger brothers. It was odd behavior for the devout Catholic who never smoked or did drugs, and went to Mass every Sunday.

"My mother saw right away that I wasn't the same person," he said.

There were other problems besides alcoholism and anger issues; Saenz also began to have nightmares.

"[In nightmares] I thought I was fighting everybody and talking in a foreign language -- Vietnamese," he said.

He said that he had felt guilty for surviving when so many of his comrades perished.

"I was just miserable because I was thinking about guys that I left behind," he said. "You become better than brothers over there. I don't know why I made it out of there and not my friends."

His struggle with his personal demons continued for well over a decade.

"I had a lot of personal problems dealing with anger, isolation, quick temper..." Saenz said. "I got pulled over several times, and I'd wind up in jail."

His erratic behavior also put a strain on his efforts to lead a married life.

His first wife, a former high school sweetheart, could not cope with his drinking, Saenz said, adding "I remarried again. Same thing, got divorced."

After two divorces, Saenz decided to finally seek treatment from the Veterans Administration. He was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder and alcoholism.

"I needed a way out," he recalled.

At the time of his interview, Saenz had been attending therapy sessions at his local Veterans Affairs facility in Houston for 20 years and had been sober for seven. He made amends with his ex-wives and his children, Gracie, Ben, Jr., Christopher and Andrea. He said that he had close relationships with his seven grandchildren and five great-grandchildren. When asked about regrets, Saenz said he had only one: that he couldn't bring people home from Vietnam.

But Saenz said that he had learned to deal with the traumatic experiences and was optimistic about the future.

"I'm living my life day by day," he said. "If it wasn't for these groups I go to, I wouldn't know where I'd be today."

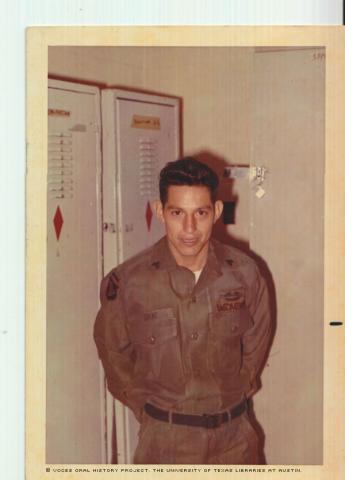

Saenz was awarded the Purple Heart; a Bronze Star; an Air Medal; a Good Conduct Medal; an Army Commendation Medal; a Combat Infantry Badge, and the Vietnam Service Medal. He retired from the U.S. postal service and, at the time of his interview, was living in Houston.

Mr. Saenz was interviewed by Gilbert Song at the University of Texas Health Science Medical School, in Houston, on April 9, 2011.