By Melissa Mendoza

“Most of my friends, they say, ‘Let’s join the Navy,’” said Benigno “Tony” Gaytan, when asked why he signed up for the Armed Forces during World War II.

“I said, ‘OK.’”

At 17, Gaytan was working as a stock boy at a five-and-dime store in Laredo, Texas. The United States had been involved in the war for more than a year. He recalled the irony of unpacking a shipment of clay toys marked “Made in Japan,” the country in which he’d soon find himself battling in the Pacific for his life and country.

By the time he joined the service in 1943, U.S. troops had recovered key stronghold Guadalcanal from the Japanese. But the war in the Pacific was far from over, and would continue until Japan’s official surrender on Sept. 2, 1945.

Gaytan recalls cadet training in Corpus Christi, Texas, to which he referred as his “first mission,” and then Uncle Sam sending him to Coronado Island Marine Base in San Diego, Calif.

“We learned everything over there. How to go with a target,” among other skills, he said, making soft artillery sounds.

From the marine base, Gaytan recalls getting sent to Camp Shoemaker, also in California.

***********

Gaytan knew about war as a boy. His father, a stone contractor who built houses in Laredo, Texas, fought in the Mexican Revolution as a lieutenant colonel and received numerous decorations, including the Mexican Purple Heart.

“He got everything,” Gaytan said.

Among others, Gaytan’s own medals include the World War II Victory Ribbon, Naval Occupation Medal and Korean Service Ribbon with three stars.

Born in Laredo on Feb. 13, 1926, he had 12 siblings – nine brothers and three sisters. He attended St. Augustine school in Laredo through the eighth grade.

In 1950, Gaytan married his wife, Francisca, in the adjoining San Agustin Church. He recalls life revolving around his close-knit community.

“They’re sincere people,” said Gaytan of his former neighbors in Laredo. “The people over there, we know each other.”

But in the Navy, the South Texas-bred sailor was far from home, and merely another seaman on his assigned ship, the U.S.S. Telfair, a Haskell-class attack transport stationed in Okinawa. Among the mix were French, English, Greeks and Italians. Two other Mexican Americans were also on the ship, recalls Gaytan, adding that he never felt anxious about segregation onboard.

“I always feel at the top,” he said. “I never feel like I’m lower than anyone else – especially in the Navy, no matter what rank.

“Maybe I got used to being the king,” he said, adding that fellow sailors would always say, “Tony can take care of that.”

Gaytan recalled a Polish American named Andy telling him before sailing to the Pacific, “You’re going to see action, Tony.” And it wasn’t long before he did: On April 2, 1945, at approximately 5 a.m., a Japanese plane rammed into the starbord side of the Telfair; then flipped over and hit the ship’s port side.

American troops had begun the invasion of the island of Japan the day before. The campaign would last nearly three months before U.S. troops successfully gained control.

Gaytan described the enemy ships as “a-screen boats,” because they were covered with a light smoke to deter detection. He was 50 to 100 feet away when the airplane hit.

“I could have got killed right there. … I fell off real bad,” he said, wincing at the memory of an injury to his right knee, tapping his leg lightly.

“Still I can hear those bullets,” he added, making whooshing sounds, “hitting right at us.”

***********

Though Gaytan wasn’t shot, he was a changed man.

The 19-year-old seaman second class was discharged Jan. 11, 1946, to Camp Wallace in Texas. He soon discovered the impact the war had on his friends – the same ones who’d convinced him to enlist, and whose experiences made him aware of a different reality upon his return.

He recalls his friend Jose “Joe” Ramon, who died in Germany in 1944. A comrade in Joe’s unit told Gaytan that he and Joe had survived hand-to-hand combat together. As their unit moved to the next battle, Joe realized his gear was missing. He went back to retrieve the much-needed supplies, despite the risk of active mines.

Joe’s comrade told Gaytan that, after safely gathering the equipment, Joe sought his comrades’ approval and raised the items over his head. But on his way back, “a mine explode[d] him,” Gaytan said. “He just forgot to think about it.”

Gaytan served as a pallbearer when Joe’s body was returned three years later to Laredo.

Another friend, Ramiro Moran, “got his boat hit by plane or torpedo or something like that,” said Gaytan, who’s unsure where Ramiro was fighting. Back in Laredo after the war, Ramiro asked about Gaytan’s tour of duty, and told him, “Tony, mine was awful, Tony. On that island, it was bad,” Gaytan recalled.

After his service in the Navy, Gaytan received training as an auto mechanic, working for various car dealerships in San Antonio, Texas. Now retired, his cheerful attitude belies his age.

“If I make it to 81, I’m gonna make it to 85, 90,” he said.

Despite the years passed since his time in the Pacific, his memories remain permanent.

“War that you see, you never forget,” Gaytan said. “You talk about it. … Or you want to forget it.

“I never forget about the plane that hit my ship, because it’s right there. You never, you know, forget that.

“You got to live with it, that’s all it is. You live with it, that’s all.”

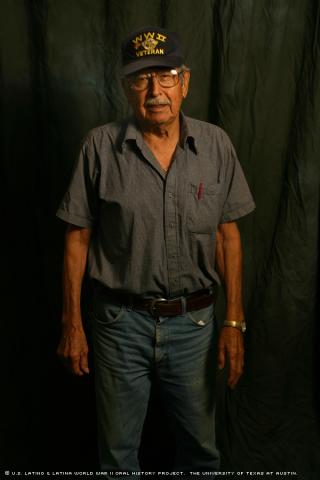

Mr. Gaytan was interviewed in San Antonio, Texas, on August 4, 2007, by Amanda Peña.