By Kathryn Wilson

A pile of manure saved the life of Benjamin Alvarado during World War II in 1944.

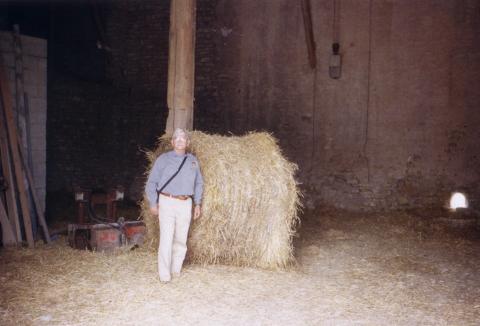

A private in Gen. George S. Patton's Third Army, he served in the 317th Infantry Regiment of the 80th Infantry Division. Alvarado and three other soldiers were positioned as outposts in St. Genevieve, France. The four soldiers were in a small farmhouse when they saw German forces approaching.

Before they could escape to warn the rest of the United States troops, a storm of artillery shells trapped them inside the farmhouse. The soldiers scrambled downstairs to the basement -- three of the men climbed inside a large wooden box, while Alvarado was left with no place to hide.

"There was a pile of manure on the side of the door -- dry manure, so I jumped in there and started covering myself up," Alvarado said. "And I just left a little bit of my eye looking out."

The German troops took over the house and set up headquarters upstairs. For 72 hours, Alvarado says he was forced to lie under the animal manure, until U.S. forces bombed St. Genevieve. The Germans were driven from the farmhouse and four men were finally able to escape unscathed.

"It's funny when you're young. You think you're going to live forever," he said, remembering he and his buddies were armed with only small firearms during the brief German occupation of the farmhouse.

Born in 1924 in Argentine, a district inside Kansas City, Kan., Alvarado was orphaned after his mother died of tuberculosis when he was almost eight years old.

His Uncle José and Aunt Conception soon adopted Alvarado and his brother and sister. While José worked for the Missouri Pacific Railroad, Alvarado attended a mixed-race school in the area and worked summer jobs for extra cash.

"As long as I never felt hungry, I was fine," he said. "Clothing was not something that you would change every day. You'd wear a pair of pants or a shirt a whole week before you changed. And a pair of shoes would have to last you for a whole year or until the soles were gone."

In 1943, Alvarado met the love of his life at a swimming pool in a local trailer park. Vicki Alvarado was 15 years old and thought the 18-year-old man was much too old for her, but Alvarado was convinced he’d found true love.

"To me, it was a serious courtship," he said.

Their love affair was cut short, however, when Alvarado was drafted into the Army in July of 1943. Soon, he was on his way to basic training at Camp Fannin in Texas.

"I actually enjoyed basic training. I had clothes, shoes to wear, three meals a day," said Alvarado, who added that going to war was the scary part.

After basic training, he was assigned to the 410th Infantry Regiment, 103rd Infantry Division, then training at Camp Howze in Texas.

"They needed some volunteers to go overseas. And my sergeant says, 'How 'bout you, Alvarado?'

And I says, 'I'll go when my turn comes.'

And he says, 'Well, your turn has come!'" Alvarado recalled.

The 18-year-old was then transferred to the G Co. of the 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division and trained in England for a month in preparation for D-Day, the Normandy Invasion, in June of 1944.

"It was like Saving Private Ryan," Alvarado said. "The worse part was not being prepared to hear all this racket and noise. It sounded like street cars going back and forth. I thought I was going to die."

Alvarado remembers wading with 60 pounds of supplies on his back with his fellow troops past the floating remains of the first wave of Allied troops, stepping over dead bodies as he and the others maneuvered onto Omaha Beach during one of the bloodiest encounters of the invasion.

After taking Omaha Beach, Alvarado says his unit moved on to the town of St. Genevieve, the scene of the messy farmhouse occupation.

Once Alvarado and the other three soldiers had escaped from the farmhouse and rejoined their outfit, he says they were shocked to see a pile of dead bodies of Allied troops Germans had shot in the days before.

Upset by the grisly sight, Alvarado says he and some other soldiers were ordered to search the town for prisoners of war. Behind the remains of one building, Alvarado recalls discovering three young German boys waving white cloths, shouting "Kamarade! Kamarade!" as they came out from hiding.

Alvarado says he took the boys as prisoners to his sergeant.

"He was really angry. He threw this automatic weapon at me, and he says, 'Kill them!'" Alvarado recalled. "So I threw it back at him and said, 'If you want 'em dead, shoot them yourself'."

Alvarado would regret the incident for the rest of his life. As he walked away, he recalls hearing the sound of rapid firing and the screams of "Muda! Muda!," which means "mother" in German. All three boys were gunned down, he says.

In retrospect, he says he believes he could have saved the German boys' lives had he taken them as his own prisoners of war.

On Sept. 26, 1944, Alvarado was struck by shrapnel during an explosion in a battle near Moivron, France. He was sent back to England, where he recuperated for three months in the 106th General Hospital. From there, he was placed in a non-combative unit called the 129th Military Police in Bad Kissingen, Germany, until the war's end in 1945.

After the conflict ended, Alvarado was flown to North Carolina, where he remained in the military, sorting out clothing in an Army warehouse for two months. When the Army honorably discharged him, he returned to Kansas City and enrolled in junior college, later opening an advertising business with this future wife.

Although they hadn’t kept in touch during the war, Vicki and Alvarado married when he was 24 years old.

The Alvarados have been married for 53 years and have two daughters and three sons. All three sons enlisted in the Navy and he has a grandson who’s a Marine stationed in Japan.

Having experienced nearly four years of war, Alvarado has gone through many close calls and life-changing experiences. He admits the war wasn’t a good thing and many lives were wasted.

"You never get rid of it; it's just kinda sad," Alvarado said.

Mr. Alvarado was interviewed in Kansas City, Missouri, on August 2, 2003, by Nicole Cruz.