By José Andrés Araiza

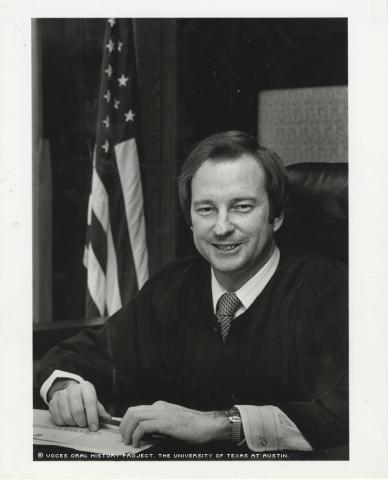

Bob Perkins spent 36 years as an elected judge in Travis County. Perkins attributes his strong ties to the Mexican-American community as one facet for his worldview; this group was his main base of support and proved to be decisive in his first run for office.

Perkins retired in 2010 from the 331st Criminal District Court, where he presided over numerous high profile cases against prominent elected officials. Perkins hopes his fair administration of these cases sent a message about a system that often favors the affluent.

"The more resources you have, the better lawyer you get. The better lawyer you get, you should get a better deal," Perkins said. "With me being there, there wasn't going to be a deal where this guy was a rich Anglo so the plea deal this guy is going to get is better than anyone else."

Perkins' perspective is influenced both by his upbringing along the Texas-Mexico border and his later involvement in Austin's Mexican American community. For many Mexican Americans in Austin, Perkins is one of their own – a Spanish-speaking Anglo who loves to sing with mariachis and is fighting to preserve Mexican American heritage.

He was born in 1947 in Laredo, Texas. His parents, William Anton and Carol Salisbury Perkins, were educators who taught at various schools in South Texas. He spent most of his childhood in Eagle Pass, a town with a large Mexican-American community.

"One of the things about living on the border is you realize there are two ways of doing things: there's the United States way. There's the Mexican way," Perkins said. "I think people who reside on the border … you learn tolerance."

As a child, Perkins said he never faced discrimination or witnessed prejudice against Mexican-Americans. In Eagle Pass, Perkins said, classes were fully integrated. He also recalled attending school with the children of the community's migrant farmworkers.

Perkins grew up speaking Spanish because both his babysitter and his mother spoke it to him when he was a child. His mother, whose father was a mining engineer, had lived in Mexico for 15 years. His ability to speak Spanish would later serve him well.

In Eagle Pass, Perkins read Arizona senator Barry Goldwater's 1962 book, Why not Victory?: A Fresh Look at American Foreign Policy. He was so inspired that he volunteered for the Goldwater campaign in Eagle Pass. His parents, both liberal, did not discourage him from his political activity.

"When I read the book, I was like, 'Yeah, this guy's right'… I was two to three years removed from playing army and the United States would always win… So I very much believed in the U.S. being Number 1," he said.

He carried that political ideology as he enrolled at the University of Texas at Austin in 1966. But once at UT, Perkins began questioning his beliefs. Returning to Eagle Pass during his freshman year at UT, after being exposed to housing in Austin, he finally took notice of his hometown's substandard housing stock

"I can remember driving by those houses and saying these people are poor," Perkins said. "Once I came back with different eyes, I realized …that conservative philosophy … in practical aspects didn't work."

Disillusioned with the Vietnam War and conservative ideology, Perkins left the Republican Party in 1968 when Richard Nixon won the Republican nomination to run for president.

"One of the main things about America is the right to vote," he said. "If you had told the American people that we had cancelled the elections in South Vietnam, a lot of people would have said, 'We don't have any business being there.'"

Perkins' political beliefs were being transformed at the same time that he was becoming more involved with Austin's Mexican American community. In June 1969, he married Yolanda Velasquez, whose father was a driver for Roy's Taxi. He was Roy's brother. (They divorced ten years later.) He also started announcing for the predominantly Mexican-American softball teams that played at the Pan American fields. The East Austin Mexican/Chicano community embraced Perkins, leading to relationships that would later prove essential to his political involvement.

After graduating from UT in 1970 with a bachelor's in political science, Perkins enrolled at UT's law school. That same year, he supported a Democratic campaign for the first time, working in Sen. Ralph Yarbrough's campaign.

He next worked in 1972 for Gonzalo Barrientos, who ran for the Texas House of Representatives. Perkins was coordinator in Precinct 4, located in the southeast Austin and Travis County.

Perkins remembers the excitement around the election because it was the first time 18 year olds could vote. It was also the first election since the Sharpstown stock fraud scandal, which involved several members of the Texas state government.

"Liberals knew that they had a chance of taking over," Perkins said. "…Austin needed to throw out these conservative Democrats."

The campaign was historic for another reason. No Mexican-American had run countywide and won. Perkins does not remember any overt racism expressed during the race. After getting into a runoff against Wilson Foreman, the incumbent, Barrientos lost by 1,000 votes. Two years later, Barrientos ran again and won by 94 votes.

In 1974, Perkins would run his own campaign. After being encouraged by friends from the local Mexican-American softball league, Perkins ran for Travis County Justice of the Peace Precinct 4. The precinct encompassed the southeast portion of the county — an area with a large Mexican-American population.

The incumbent was John Ross, a farmer. Another challenger emerged: Dan Ruiz, a college friend of Perkins'. Neither Ross nor Ruiz were lawyers, which is why Perkins chose the campaign slogan: "A Lawyer for a Lawyer's Job." Even though Perkins used his fluent Spanish to communicate with voters, he lost the Mexican-American vote.

"A lot of Chicanos were going to support Dan because of his ethnicity. White liberals would not vote for me. Because they said 'No, you're not a Chicano. We're not going to vote for you. That needs to be a Chicano in there,'" Perkins said.

In the first vote, Perkins received 30 percent of the vote, Ruiz got 42 percent and Ross 28 percent. But in the runoff between him and Ruiz, Perkins got all of Ross' supporters and Ruiz' white student liberal base evaporated. The runoff took place in the summer, when students had left Austin, he said. Perkins took office on Jan 1, 1975. In 1982, he was elected to 331st Criminal District Court and served there until 2010.

During his time as district judge, he heard notable cases that involved high level public officials. Perkins was initially assigned the case against Congressman Tom Delay, R-Sugar Land, but Delay's legal team argued to have Perkins removed from the case. According to The New York Times, Delay's team believed Perkins was biased because he gave Democratic candidates around $5,000 in donations over a five-year period, including the 2004 presidential election campaign.

"In [Delay's] world, the great dictator is the political party… In my world, the great dictator is the law. The law is the law. They're either going to be right or wrong," Perkins said. "I have no question that I could have been fair and would have been fair to him."

Delay was convicted in 2010 and sentenced to three years in prison. Perkins said if he had heard the case, he probably would have found it hard to sentence Delay to prison.

"It's a $190,000 of money laundering. It's not a crime of violence," Perkins said. "In term of being eligible for probation and in term of fitting all the indexes for somebody who can be rehabilitated, Tom Delay fills all those things."

In 1991, Perkins made national headlines for jailing Texas Speaker Gib Lewis, a Democrat, for not showing up to court to face misdemeanor ethics charges.

"It was a question: was I going to run my court? Or was he going to run it? Once I did that, everyone knew that I wasn't going to put up with stuff," Perkins said. "It didn't matter who you were, you were going to have to follow the law."

In his retirement, Perkins' work in the community continues. Perkins is now leading an effort to correct the spelling of Manchaca Road to Menchaca Road. After researching historical records, Perkins realized that the road takes the name of José Antonio Menchaca, who commanded a company of Tejanos from San Antonio and fought in the Battle of San Jacinto.

"Here is this guy who is a hero of the Texas revolution. They name a town after him, and they don't spell it correctly," Perkins said. " In my research, it's the only place in Texas that is named for a Texas hero and his name is misspelled."

Perkins must raise $50,000 to correct the street signs in Austin. While he continues to work on the Menchaca effort and hear cases in his retirement, Perkins ultimately hopes he's remembered for his fairness and his work on the bench. One of his proudest accomplishments has been gaining more consideration for crime victims in the criminal justice process.

Judge Perkins was interviewed by José Andrés Araiza in Austin, Texas, on March 31 and May 2, 2014.