By Ali Vise

The clock read 4:30 when an explosion shook Camilo Medrano awake and sent him sprinting in the darkness toward the moans and calls for help. He felt around with his hands, he grabbed the limbs of the men scattered on the ground, confirming casualties while searching for survivors. This was his job.

It was a job that took Medrano from his hometown of San Antonio to the horrors of the Vietnam War.

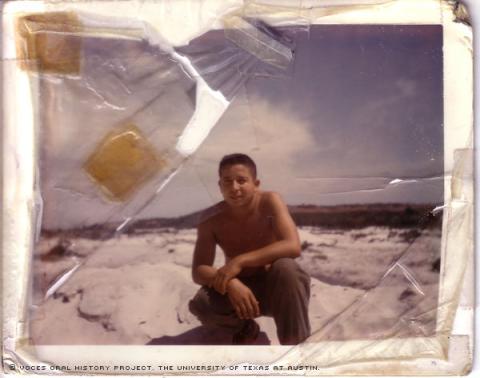

Medrano, who was born in 1943, said his family's tradition of military service had inspired him to join the Navy Reserve while he was still in high school. His father, Porfirio, brother, Rene, and his uncles had all served in the military.

While he was in his early teens, these men taught Medrano and his cousins how to set up an ambush. Later, he realized that he had resorted to using these techniques when he was in combat. By joining the Navy Reserve, he was doing what was expected of him. He later decided to try to become a corpsman in part because he had a brother-in-law who was a Navy corpsman. When he scored high on the Navy's placement test, Medrano chose hospital corps school.

"Looking back, the only way a Hispanic could probably do good in life was by joining the military and getting some kind of training and education that could serve them when they got out," Medrano said.

His earliest childhood memories consist of creating games out of milk bottle lids, playing marbles and swinging from trees. He lived in a duplex with his family and cousins four blocks from downtown San Antonio.

"It was just a carefree time," he said. "Some people might have considered us poor, but we didn't see it as such at that time."

Both his parents, who were born in Mexico, stressed the importance of speaking English at school and Spanish at home during his elementary years. His light skin and freckles set him apart from other Mexican Americans.

"I had acquaintances who would really get mad at me for not speaking Spanish at school," he said. "That set me apart from most of the Mexican-Americans at school. That is when I first started getting into scuffles with kids."

At family functions, Medrano recalled his father and uncles, veterans of World War II and the Korean War, gathering in the corner, away from the children, and talking about their war experiences. He believed this protected him from hearing battle stories at a young age.

He went to basic training in June 1962 as a Navy reservist and enlisted into the regular Navy in July 1962, when he was 19.

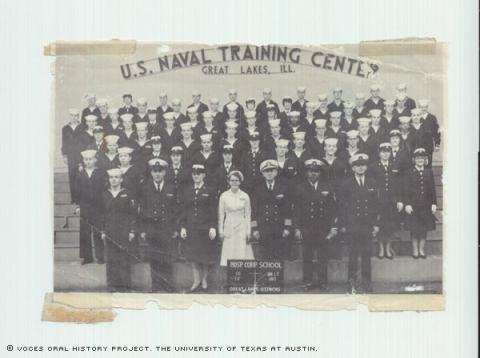

Medrano's first trip outside of Texas also brought his first experience with cold weather. He attended Hospital Corps School in Great Lakes, Ill. He started in August 1962 and finished in February 1963. While he was on leave from corps school on Nov. 23, 1962, he married Esther, whom he had dated in high school. Later, while he was stationed at the Corpus Christi Naval Hospital, he and Esther had their first son, Anthony. The following year, his second son, Christopher, was born with cerebral palsy. Their daughter, Celine, was born in 1971.

He reported for eight weeks of training to Camp Pendleton, Calif., and then transferred to the 3rd Marine Division of Field Medical School, where he learned how to take care of those wounded in battle, as well as how to use a gun.

After training, he was scheduled to leave El Toro, Calif., for Okinawa enroute to Vietnam when a fellow corpsman named Jim, who knew of Medrano's disabled son, talked to Medrano about returning home before leaving for Vietnam. Medrano informed him that he was short $50 to make the trip. Jim, whose last name Medrano could not recall, immediately provided him the money to return home.

The following day, the flight he had originally been scheduled to fly on crashed into a mountainside, killing everyone onboard. He was forever grateful to Jim, who he never saw or heard from again.

"I've never placed that much importance on money after that," he said. "I do believe in helping people if they are in need."

He said that through training he had received adequate medical knowledge about how to respond in battle, but he felt that he was not prepared mentally for what he would endure. After his first experience in combat, he said that he no longer valued his own life. .

"A Navy corpsman with the Marine Corps has to be just as strong, if not stronger than the Marines," he said. "They came to us with their problems."

In Vietnam he was assigned to the 2nd Battalion, 4th Marine Regiment, 3rd Marine Division.

On patrols and operations, the corpsman's job required him to monitor the condition of the troops during their five-minute breaks. Also, as a member of a Medical Civil Action Program (Medcap) team, he visited Vietnamese communities, providing vaccines, helping wounded and giving gifts to the children.

"I couldn't understand what we were doing there," he said. "The thought that came to me was that we were imposing something upon them that didn't make a difference to them. I had my doubts about what we were doing in Vietnam."

But the most difficult part of his job was seeing the horrors of war.

"Treating the dead and wounded. Holding a dying Marine in my arms in an attempt to comfort him. Hearing the cries of wounded Marines that I was unable to attend to because I was told by a Marine officer, 'I've already lost four corpsmen -- don't go out there," Medrano said.

He also recalled the devastating effects of war on civilians, especially children.

He received his honorable discharge in August 1966, after 13 months of military service. His highest rank was Hospitalman E-5. Among the medals and awards he earned for his service were the National Defense Service Medal; Navy Good Conduct Medal; Vietnam Service Medal with three bronze stars; Naval Unit Commendation, and the Republic of Vietnam Meritorious Unit Citation.

Medrano quickly found work at a printing company and later joined the U.S. Postal Service in 1967.

He believed the war changed him. He said that his mental distress resulted in alcohol use and combat nightmares haunted his sleep. He had auditory hallucinations -- the sounds of mortars, machineguns and other weapons firing -- that kept him from sleeping. In order to subdue post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, he sought medical help in 1975. But his PTSD was not diagnosed until 1988. Still he was able to look back on his wartime experience as also having impressed him in some positive ways.

"The Vietnamese were beautiful people, they had beautiful customs and traditions," he said. "At some point, had it not been for the war, I wouldn't have found that out."

Mr. Medrano was interviewed by Ali Vise in Castroville, Texas, on Nov. 6, 2010.