By Kenneth Cantu

Back when Rosie the Riveter was proclaiming to women all across the U.S., “We Can Do It!” Carmen (Salaiz) Esqueda Abalos proved it.

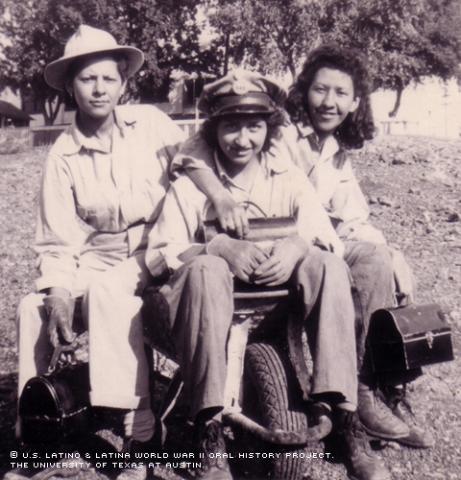

Her husband, Mike, having enlisted in the Navy, Abalos joined the war effort by working in the Kennecott mine in Santa Rita, N.M., taking a job that once belonged to a man.

“They were doing a job over there, and so they had to have a replacement over here,” said Abalos, who at the time was only 21 years old and had a young baby named Mike Jr. “[We were] just looking forward to them coming home.”

Abalos helped out in the carpentry shop by sorting nails, moving lumber and cleaning walls, prepping them for the painters.

“We used to do various things. … I didn’t have to work on the railroad, [but] a lot of ladies did,” she said, emphasizing how lucky she was.

Abalos had been working various jobs almost all her life. In the fields, “it didn’t matter who worked, women or men, as long as the work got done,” she said.

When she was five months old, she says her father abandoned her family. Her mother remarried and her step-father adopted her. She would change her name from her father’s surname, Salaiz, to her stepfather’s, Esqueda.

The Esqueda family moved to Colorado for a time, where Abalos helped her stepfather work the fields by stacking hay. He also worked recruiting migrant laborers for farmers. Toiling from sunrise to sundown, they only got Sundays off to rest, Abalos recalls.

The clan eventually moved back to New Mexico, where an unemployed Abalos was able to spend more time enjoying her youth. She liked going to dances with friends, jitterbugging and polkaing the night away. In fact, it was at a dance where she met her future husband, Mike Abalos.

“My husband’s brother introduced me to Mike,” said Carmen, who’d come to the event with a boyfriend.

That didn’t stop her, however, from hanging out with Mike at the following dance, held at the local casino. She recalls Mike asking her if she’d like to have a coke with him.

“So I went, and I didn’t even give a thought to the other one that I had gone [to the dance] with,” she said.

When they returned, “the boyfriend was so mad he was just boiling,” recalled Abalos with a chuckle.

The couple dated while Abalos worked as a housekeeper, which she did until they got married in August of 1941. Mike Jr was born shortly afterward, and three months after that, his father decided to enter the Navy. The couple would eventually have four more children: Rodolfo, Richard, Pat and Arlena.

Working at Kennecott, Abalos and the other women had to adapt to the new environment, and some men, she recalls, didn’t help the transition.

“At first, we were kinda weary of the men that were left there. They sorta looked down at us.”

Not only did she have to put up with sexist attitudes, she had to endure other social prejudices. Anglos and Mexican Americans were separated not only in the mine – there, Anglos had their own entrances to the factory, their own lines to receive paychecks – but also in town, where the neighborhoods were divided by railroad tracks, Abalos said.

Prejudice would continue to be an obstacle even after the war years. For example, one time Abalos had to confront the school about persistent problems her daughter was having with some Anglo children. Abalos was furious.

“You are no better than I am,” she recalled telling the teacher, who responded with sympathy and frustration, Abalos added.

Through the tough times of a country at war, Abalos worked hard. She also struggled with being a minority and a working woman. These battles have shaped her life, beliefs and the values she has passed down to her 5 children, 19 grandchildren and 23 great-grandchildren, she says.

Because of her husband’s experiences during the war, she became involved with the Veterans of Foreign Wars and the Disabled American Veterans, holding various positions of power and respect within both organizations.

“We are still right behind them … working to support our veterans,” Abalos said.

Mrs. Abalos was interviewed in Hurley, New Mexico, on July 15, 2004, by Brenda Sendejo.