By Anjali Desai

Cayetano Casados had a floating, front row seat for the historic Normandy Invasion of World War II.

"We were the first ship to be fired on and the first ship to fire in the invasion," said Casados of the campaign that led to the allied victory over Germany.

"We had some very close calls. Sometimes there would be shrapnel all over you. But I was very fortunate, I only lost one man," he said.

Early in 1944, Casados’ crew left from Boston and landed in Northern Ireland. They didn’t know when the invasion would take place until Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower boarded the USS Quincy, Casados says. According to the Naval Historical Center Web site, during June of 1944, the USS Quincy provided gunfire support for the Normandy invasion and bombarded German positions around Cherbourg, France.

The crew had trained for two months with other ships in the fleet.

On June 5, 1944, ground warfare efforts to free Europe were to begin. The weather was so terrible and water conditions so dangerous that the invasion was delayed. After a 24-hour wait, the fleet returned to the Normandy coast, preparing for D Day.

"There were so many ships around us in the English Channel. We knew we were headed for something [big]," Casados recalled.

The Quincy anchored at about 2 a.m. on June 6 and sailors manned their stations.

"I was anxious to see what we were going to do," he said.

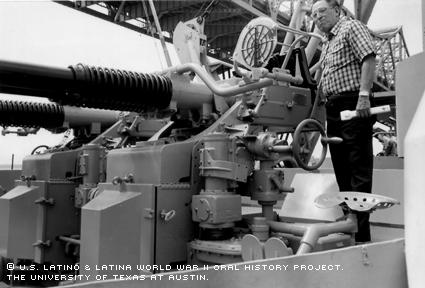

Finally, Casados, a gun-crew captain, was told a German spotter plane was flying over them. That's when the shooting began.

The sole victim in that initial battle was the oldest member of the gun crew. Because he was 31, he was nicknamed "Pop." Casados was 20 at the time.

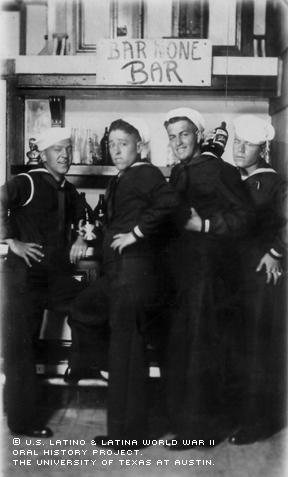

Casados remembers many of his younger comrades from big cities had been given choices after getting in trouble, so they ended up in the Navy as an alternative to punishment.

While Casados was the only Latino in his crew, he says he never suffered any serious discrimination. Yet he was puzzled that other sailors would ask him what he was doing fighting the war, since Mexico wasn’t involved.

"I felt sorry for these college-educated guys. At that time, I could name every capital and every state and yet one guy with two years of college experience from Duke didn't even know where New Mexico was," he said.

They would also joke that he talked funny. In turn, Casados teased them about their Bostonian accents.

"We always laughed it off," he said.

Casados was born on Aug. 7, 1923, in Cerrillos, N.M. His family lived in Cerrillos and Madrid, small towns about three miles apart. As a youth, Casados spoke Spanish and later learned English in school.

"I'm from the greatest generation," he said. "I went through the Great Depression and World War II, from which I came back, thank God."

Casados' father worked at a paying job only one day a week. It was adequate for covering the rent in Madrid, but not enough to raise a family of seven. So the family also raised chickens, rabbits and pigs for food.

"I remember killing a pig every so often. [Life] was hard. We survived," he said.

The second oldest in his family, Casados remembers that to make ends meet he and his brothers worked for three consecutive summers mining gold in the hills of Dolores, near Cerrillos. He dropped out of school after the 11th grade to go to work full time.

In Cerrillos, Casados was putting up Christmas lights throughout the city on Dec. 7, 1941, when he learned the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor.

"When I heard the news I knew right away I'd be called for war because I was already 18," he recalled.

He was immediately called to Santa Fe and was one of five from a group of 40 chosen to join the U.S. Navy. His father had served in the infantry during World War I and encouraged his son to serve in the military.

After boot camp in San Diego, Casados attended gunnery school and graduated as a gunner's mate, a third-class petty officer.

Latinos were 25 percent of his training company. Casados was the only one assigned to Boston, where he attended firefighting school and took English courses.

On Dec. 15, 1943, he boarded the Quincy, a new, 13,600-ton heavy cruiser considered the fastest and having the most modern weaponry at the time. It would be his only ship assignment.

Casados didn’t make his first visit back home until he’d served 21 months of duty.

"My parents had no idea where I was, they had no letters," he said.

When he reached home on 15 days of liberty, his mother started crying.

"The community treated me like a hero. Everyone offered to buy me a beer. Relatives were very happy to see me," he said.

After Normandy, Casados' ship operated near the south of France. Later, the Quincy participated in the battle to take Okinawa. The Quincy also operated near Kyushu, Honshu and Hokkaido. Casados also participated in the dematerialization of Izu Island and the Japanese mainland.

He says he was told his ship was only 50 miles from Hiroshima and Nagasaki when the United States dropped the atomic bombs.

Casados finished his duty on January 9, 1946, after 25 months in the Navy. He received medals for the European and Adriatic Theaters, each with two stars; a World War II Victory Medal and a Good Conduct Medal. Eight years ago, he received the Normandy Invasion Medal from France.

After the war, Casados worked as a general manager at Empire Builders for 32 years.

Today he lives with his wife in Santa Fe. They have one daughter, Paulina, and a son, Fernando.

Casados says Latinos have changed.

"When we were growing up, we were timid," he explained.

He remembers sitting by his baseball coach, hoping and waiting for the coach to put him in. In contrast, his son would practically beg the coach to play.

"[Latinos] are more outgoing. It is a different generation," Casados said.

For more than 25 years, Casados played an active role in the St. Vincent de Paul Society.

"I wanted to help the poor people because I know what it is." he said.

And he advises the youth of today to take advantage of education and attend school.

"It's the only salvation," Casados said.

Mr. Casados was interviewed in Santa Fé, New Mexico, on November 3, 2002, by Normal L. Martinez.