By Yolande Yip

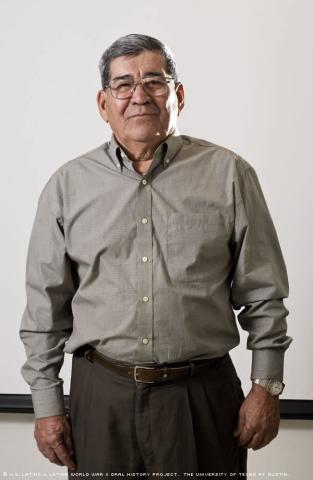

A self-described “simple country boy” who served in World War II’s European Theater alongside other men from humble backgrounds, Concepción Garcia Morón said a lack of self-awareness led to a friendly-fire death one February within his company.

“It was our buddies shelling us because . . . like I said, line infantry doesn’t know anything . . . you hold that ground regardless,” said Morón, of the Luxembourg-area incident. “You don’t know where you’re at. Just, ‘Be ready in five minutes. Be ready in 10 minutes.’”

“We were just plow guys,” he said. “We didn’t know anything about politics. We were just weak minds and strong backs.”

Morón was the youngest of four children born to José Morón, a farmer and sharecropper, and Petra Garcia Morón. Petra died in 1939, when Concepción, or “Chon” was 13.

Morón and his three siblings grew up in Beeville, Texas, about 50 miles northwest of Corpus Christi. In addition to working with his father on the farm, Morón attended Our Lady of Victory Elementary School, and then transferred to Westside Elementary School. He ultimately quit the classroom.

“I was not learning, so I went to work,” he wrote after his interview.

It was Dec. 7, 1941, and Morón and his family, having just returned from Mass, were shooting marbles and listening to polka music on the radio at his uncle’s house. “All of a sudden – Pow!” Morón recalled.

“‘We interrupt this program’ – it was in English – and it [the radio broadcaster] announced that the Japanese just attacked Pearl Harbor.”

For the next three years, Morón did what many Americans on the home front did: collect scraps of aluminum foil and tin cans for the war effort.

Then Uncle Sam drafted Morón, at 18, and he was inducted into the Army in February of 1944. He reported to Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio; completed Basic Training at Fort Hood, near Killeen, Texas; moved to Camp McCoy, between Sparta and Tomah, Wis.; got assigned to Company L of the 304th Infantry Regiment; then reported to Camp Miles Standish in Massachusetts.

Morón ultimately boarded the USS Brazil and landed in Normandy, France. Although he took part in the Ardennes, Rhineland and Central Europe campaigns, he prefers not to discuss them.

“I’m not good at reliving things. It brings bad memories,” Morón said.

According to his military records, Morón earned several awards, including the World War II Victory Ribbon, Good Conduct Medal, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Ribbon and three Bronze Service Stars. He was also awarded a Bronze Star for continuing to lead his squad through enemy fire until it encountered heavy machine-gun fire. Morón then crept to a point from where he fired upon the attackers, forcing them to surrender.

Morón said 2nd Lt. Sylvester Patton promised him the Silver Star for his actions that day. In an affidavit Morón signed May 31, 2005, he recalled Patton’s promise. “All this was said by mouth,” the affidavit reads.

The document says he was a scout on patrol, “trying to make contact with the Russians,” and that he picked up two machine-gun nests and signaled to his squad to “hit the ground.”

“For that reason, we did not fall in their trap,” he writes. Rather than cause great damage, the Germans were only able to hit a rifle stock.

Later, while on a three-day pass to London, Morón was instructed to put on his return uniform for a medal ceremony, in which he got a Bronze Star. He never received a Silver Star.

Morón said he let the matter go until after he retired. He appealed to the Army, and a May 19, 2005, letter from the chief of the Army’s Case Management Division told him he first had to exhaust all remedies. The official, Gerard W. Schwartz, instructed Morón to prepare more forms, and to get his Congressman to submit them.

“Although nobody seem to care but me,” wrote Morón after his interview, he has not given up hope on getting the coveted honor.

“I didn’t go [to war] for decorations. [I] just happened to be there when things happened,” he said.

When the war ended, Morón stayed in the Army until he was honorably discharged March 18, 1946, at the rank of Private 1st Class. He returned to Beeville and spent some time picking cotton and working as a farm laborer.

But the military had changed him, made him aware of his rights, and he became dissatisfied with the constant discrimination he encountered while seeking further employment.

“That employment office . . . the guy who was in charge of veterans … I was mad because he said, ‘Let’s get the white boys over here. And you two [the only Mexican-Americans] over here.’”

“And he would send me to the yard, mowing the yard,” Morón recalled.

“I said, ‘Is that the reason you moved us over here, behind these guys?’”

Eventually, Morón was able to secure a position as a diesel serviceman for Reynolds Metals, a job that could support a family.

Morón said he learned a great deal in the military, though his lessons weren’t restricted to military matters. In France, for instance, he saw an apple for the first time.

“There were a lot of apples [in France]. The guys from up north, they knew because they’ve got apples over there,” Morón said. “What we’ve got over here [in Beeville] – watermelons and persimmons – I was used to that.”

On Sept. 13, 1949, Morón married Margarita Weisheimer Cano, with whom he had seven children.

Having witnessed the dangers of ignorance by blindly following orders during his military experience, Morón, who never completed his formal education past elementary school, said he was committed to getting his children through school, and that all but one completed a college degree.

“To me, school is everything for the new voice, for the new generation. God only knows how far I would have went if I’d had school,” Morón said.

Mr. Morón was interviewed in Beeville, Texas, on Jan. 10, 2009, by David Silva.