By Marjon Rostami

One day Cruz Rodriguez was picking corn and tomatoes on a farm outside of Chicago; the next day, the undocumented Mexican immigrant was preparing to go to war.

"They [the U.S. Army] didn't care if you were legal or not," Rodriguez said during his interview. "They just needed soldiers. They took Mexicans off the field and they [were sent] ... to war."

Many of the Mexican immigrants drafted to fight in the war were willing to do so, Rodriguez said. They just hoped that when they came back from the war, the U.S. government would grant them citizenship.

Rodriguez was born on May 3, 1914, in San Francisco del Rincon, Guanajuato, Mexico. His parents, Elias Rodriguez Bustos and Catalina Rodriguez Rodriguez, came from Mexico, first to Texas and then to Michigan. Cruz was seven years old when his parents brought him to the United States.

In Michigan, he and his brother Francisco, who they called Frank, worked in the sugar beet fields together.

"We picked corn, tomato, worked in sugar [beet] fields. Everything in fields," Rodriguez said.

By the time he was old enough for high school, he quit formal education and joined the migrant stream through the Midwestern states.

"In those years, people didn't care if you had a good education or not," Rodriguez said. "We Mexicans, they give us a shovel and a pick and we go work."

In 1930, his family moved to Chicago, where his father worked for the United Steel Corp. and Rodriguez began spending many hours daily in a different type of field - a baseball diamond. He played with the Mayas, the only Latino team at the time. The team consisted primarily of 17-year-old Mexican immigrant youths, he added.

"We just played with the Mayas. The other teams were no good," he said.

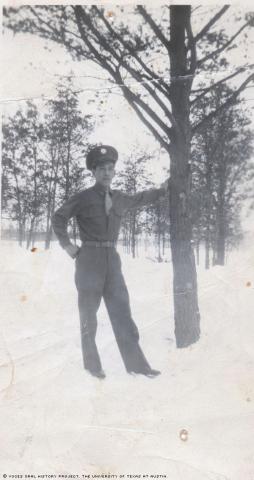

About a decade later, Rodriguez entered the military. He was told to report to Camp Grant, just south of Rockford, Ill., on Oct. 15, 1942.

Rodriguez said he actually enlisted in the Army, but as was the case with many Hispanics, he was listed as having been drafted. He hoped that, through his military service, he would gain U.S. citizenship.

After he got his uniform in Illinois, he went to Arkansas for basic training at a camp about 50 miles from Little Rock, and then to Wisconsin for jungle-survival training.

"We were ready to be shipped overseas when they cancelled it because at that time there were a bunch of Mexican kids, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22-years-old, and most of them didn't know how to speak English at all, and most of them were not American citizens or legal," Rodriguez said. "They took them off the fields to come with us."

As he recalled, no one asked for their citizenship papers as 60 Mexican immigrants, now U.S. soldiers, embarked for Burma. Their mission, he said, was to push back the Japanese and open supply routes.

Rodriguez shipped out with 30 other immigrants on a voyage that took 40 days because the vessel was forced to travel in a zigzag pattern to avoid Japanese submarines.

"It was OK," Rodriguez said. "Everybody was friendly to each other on the ship."

After the ship reached the coast of India, the men were immediately directed onto a train for another four days of travel.

"There was only one [rail] line. Jungle on this side and jungle on that side," he said. "There was nothing but jungle."

He arrived in Burma on Dec. 26, 1943. Once off the train, the men penetrated the jungle in Burma and waited for more orders.

"We were there, camping. We never camped close to a city or close to a village. Nothing but jungle," Rodriguez said.

Standing only 5 foot, 3 inches tall and weighing only 130 pounds, his weapon of choice was a Browning Automatic Rifle, or BAR, which was used as a light machine-gun. He wore a camping pack, canteen, the standard issue M1 rifle, ammunition across his chest and two grenades on each side of his waist.

On Aug. 8, 1945, less than a month before the surrender of Japan, Rodriguez was wounded in the right shoulder.

Once he got to the hospital, he recalled having encountered discrimination.

"They took me in, and they put me on the floor, on bamboo. Everyone else [who was non Hispanic White] was in cotton beds, but I was on bamboo," Rodriguez said. "I thought: 'If I survive and come back, there will not be so much discrimination anymore. I served my country now.' "

He said he was sent to the India medical section, while White wounded soldiers were taken to the regular U.S. military side.

Rodriguez left Burma in Nov. 10, 1945 and arrived in the United States on Dec. 1, 1945. He received an honorable discharge on Dec. 7, 1945, at the rank of private first class, and was awarded a Purple Heart; an Asiatic-Pacific Theater ribbon with two bronze battle stars; a Distinguished Unit badge; four overseas service bars, and an American Campaign Medal.

He recalled having faced more discrimination after returning from the war, when he began working as a laborer for Wisconsin Steel.

"I went to work, and people said, 'Hey, Pancho.' I said, 'My name is not Pancho. You know what my name is.' And they stopped calling Pancho so much.

"I risked my life for this county, and I come back, and it is the same damn thing," he said.

Rodriguez, who eventually became a U.S. citizen, married Catalina Nieto, a native of San Luis Potosi, Mexico, in 1937 in Chicago. They had two sons and two daughters. The couple divorced in September 1968. He later had three sons from a second marriage.

Rodriguez died on March 29, 2013, in Chicago.

Mr. Rodriguez was interviewed by William Luna in Chicago on Sept. 21, 2005.