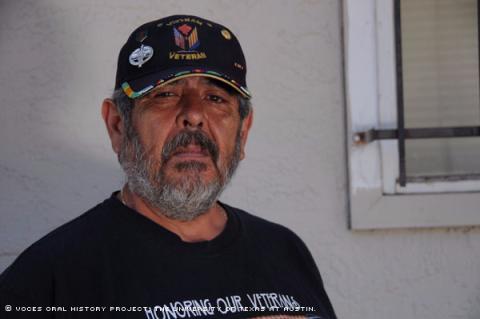

By Jonathan Woo

War can affect people in ways that no one can anticipate. Daniel Archuleta, a Vietnam War medic and Bronze Star recipient, might understand what Russian novelist Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn meant when he wrote: "Even if we are spared destruction by war, our lives will have to change if we want to save life from self-destruction."

At a point when racial and civil rights tensions were on the brink of boiling over, Archuleta struggled to find direction and guidance throughout middle and high school in a Denver community where racism and discrimination were commonplace. At Annunciation, a Roman Catholic high school in Denver, his weight and subsequent struggle with prescription amphetamines were problems targeted by the school's nuns and the priests, who saw potential in the boy and provided a foundation to build his self-confidence.

Gaining self-confidence would be a recurring theme as he developed leadership skills in the war that would challenge so many of his beliefs.

Inspired in part by his uncle, a medic who was killed in the Korean War, Archuleta joined the Army. Although his uncle died when Archuleta was only three years old, he still had a powerful impact on the young relative.

"I grew up with his memory. I have a little green jacket with his Army patches," he said. "I wore it when I was little, and my son wore it when he was small."

After high school graduation, Archuleta enlisted in the military on July 30, 1967, just weeks after his 18th birthday. He hoped to become an X-ray technician with a posting in Germany.

His father was less than pleased by his enlistment.

"My dad was furious," Archuleta remembered. "He was livid over this whole thing. He didn't want me to have anything to do with Vietnam. He wanted me to go to college and be a doctor. He had plans for me."

Archuleta was sent to basic training at Fort Campbell, Kentucky.

Despite Archuleta's Latino ancestry, he often was teased by some of his Latino companions at Fort Campbell for his "pristine White" upbringing and lack of Spanish skills. But he also believed that they had his back. One acquaintance that ultimately helped toughen him up was his Puerto Rican drill sergeant, who for three weeks would go fist-to-fist with Archuleta.

"He was sincere about the fact that he knew I was going to war, and he wasn't gonna let me be a smart-ass punk who didn't know what I was doing," Archuleta said of his drill sergeant. "He'd take me outside, and he'd beat my ass, and he'd put me to bed. He was teaching me things that I needed to learn."

Archuleta said the drill sergeant's rough treatment helped him learn how to kill and prepared him for war.

Although he would later transfer to Company D in the 1st Medical Battalion, Archuleta was set to mobilize as a medic in the 2nd Medical Battalion, 18th Infantry, 1st Infantry Division, in January 1968. It was the year of the Tet Offensive, the assassinations of Sen. Robert F. Kennedy and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr, race riots in big cities and fierce anti-war protests from East Los Angeles to Chicago and beyond.

In early February, Archuleta's unit arrived at the large base camp in Di An, South Vietnam, shortly after the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army launched the Tet Offensive, a game-changing cluster of surprise attacks against South Vietnamese and U.S. forces. It wasn't long before one of Archuleta's best friends was rushed to the field hospital. The friend had lost both legs. "He reached out and grabbed me, and he told me: 'Get your ass out there, and get even for me,' " the former medic said. This was Archuleta's rude awakening.

He transferred to the infantry and fought for his survival from that day on. Ultimately, he said, he got even not only for his friend but also for his uncle.

"You go over there a naive, innocent human being," Archuleta said. "You have no concept of what's expected of you, or what is going on in and around you at that time. And you have to rely on your wits and your individuality. And all the training in the world doesn't help. The one thing that I had in me, and I'll always believe this, is hate. I had a lot of anger, a lot of hate."

When the news of the 1968 assassination of the Rev. King arrived in Vietnam, Archuleta said that it further perpetuated the racial discord among U.S. troops.

"Right after MLK was killed," Archuleta recalled, "it turned into a goddamn race war. It really frustrated me, and it was disheartening and heartbreaking."

He recounted soldiers attacking each other, sometimes with grenades and other times by shooting them while in the field. He said it happened more than once, and there was no mistaking why it happened. He called it the ugliest part of war.

"Everybody operated individually [in Vietnam]. You got your orders," Archuleta said, "but you also had an agenda of things you wanted to accomplish. And, if it meant taking people out, you took them out. Once you were in Vietnam for a month, there was no more right or wrong. It was survival. It was animal against animal. Bare, brass tactics. There were no rules; there was nobody following any rules. There was just people with guns, being angry and taking care of business."

Some minority troops, such as Archuleta, were now fighting a war on two fronts. Many minorities "caught hell from all the White boys [who] felt they were definitely superior," creating divisions within units. Those private ruptures made for frightening circumstances during battles.

As a medic, between the divisive behaviors, his duty to care for his fellow soldiers gave him balance and an understanding of how significant life was.

Archuleta described his role as a medic not just as a medical caregiver, but also as a mother and a father. He was a leader in his unit and an anchor point. As he gained experience in the field, that role endured, but it also transformed him.

"I knew what the war was about, and I knew how to do my thing," Archuleta explained. "I took control. ... I was a mean son of a bitch, and I hurt innocent people, too. If villagers got in our way, we hurt them. People crossed us, we hurt them."

Upon Archuleta's return home, he realized that his worldview had changed.

"Nothing I believed in was ever going to be the same again," Archuleta said. "I lost my faith in God, my faith in country and my faith in human beings."

He was discharged on July 30, 1970, with the rank of specialist. In addition to the Bronze Star, he received the National Defense Service Medal, the Vietnam Service Medal, the Vietnam Campaign Medal, Combat Medical Badge, Army Commendation Medal and a Sharpshooter Badge.

He married Hortensia Rodriguez in 1971, and they had a son, Shawn Joseph Archuleta. The couple were divorced in 1992. Archuleta married Julie Coronado, an IRS specialist, on June 27, 2007.

He became active in Vietnam Veterans Against the War, the American Red Cross and the Paramedic Association of Colorado.

Archuleta suffered hearing loss because of his service and was subsequently diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder.

It greatly upset him that, when he went in 1998 to the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington, D.C., he could not find the name of his best friend, Hugh O'Brien Jr., who was killed in a mortar attack.

Looking back, Archuleta believed that, despite the trials of combat, his care for human life and his role as a medic may have helped him keep his sanity.

"If you love life," he said, "then you need to love people. And when they take that away from you, you have to get it back, or you end up with nothing."

Mr. Archuleta was interviewed by Henry Velez in Denver on Aug. 9, 2010.