By Israel Saenz

Davie Elizardo never asked for much. For a woman who grew up without an education, doing field labor throughout the day and watching one of her brothers go off to fight in the Pacific, the wellbeing of her family is all she needs.

"I just want that my grandchildren find good work and not have to struggle," Elizardo said. "They have very good opportunities."

To struggle and work hard to get by was so much a way of life for Elizardo, she hardly noticed it.

The daughter of Refugio and Constancia Elizardo, Elizardo was born Dec. 29, 1919, in the small town of San Diego, Texas.

Her father's parents migrated from Matamoros, Mexico, in search of work. Elizardo recalls her father and uncles working on a ranch called Rancho Lagunas when she was younger. She was in her early teens when she began to help out with the field work.

"They didn't pay us much," said Elizardo, remembering the workers were paid about $5 for a week of labor.

Responsibility for those around her became a major theme in Elizardo's life, as she’d end up the oldest of 12 siblings. She also recalls tending to the land and taking care of animals -- goats, pigs and sheep – of which she grew fond.

Life wasn't only work for Elizardo. She also enjoyed horseback riding and going to town to watch movies. She gave up the horses, however, after a bad experience when she was 18

An uncle had warned her about riding a particular horse, which he said was only comfortable with riders he already knew.

Young Elizardo thought she knew better; however, after mounting the horse, it ran off in a frenzy, with her clinging on. Elizardo finally threw her legs to one side of the equine and dropped off.

After that, she only rode mules.

Elizardo would also go with companions to town to watch movies: The star actors of the era, in the Mexican films, were Pedro Infante and Jorge Negrete.

To pass the time, Elizardo also enjoyed sewing.

"I would sit on the bed, sew by hand and make my own dresses," Elizardo recalled.

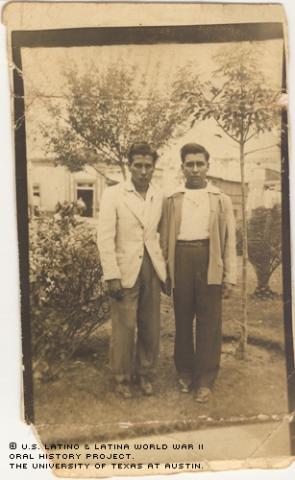

But in 1941, a pall settled over her family and community when the United States was pulled into World War II. Her younger brother, Cipriano, was drafted into the Army. On a few occasions he wrote letters home, describing different aspects of life in combat, such as what it was like being in the trenches. Elizardo and the rest of her family could do nothing but worry and pray, she says.

"Our mother had a radio," said Elizardo, "and she would get up very early, to hear what was happening."

Her little brother would soon make news stateside, as Elizardo recalls a local newspaper article detailing how Cipriano, wounded after a piece of shrapnel hit his jaw, nevertheless moved several fellow soldiers to safety.

Elizardo herself also saw a little local glory, when the Corpus Christi Caller-Times did a story on her situation of being a woman raising as many as 20 sheep at a time, as well as doing other chores.

Elizardo felt she could do particular jobs better than many of the men who were there.

"There were men [still in civilian life]," recalled Elizardo, "but they didn't have much sense for taking care of things."

After Cipriano returned, Elizardo noticed the war had changed him.

"His mind was different when he came back," said Elizardo of her brother, who now lives in Michigan. "He was very kind before."

Eventually, she and the family members who were still there would begin working on a ranch called Rancho Colorado, near Alfred, which was about 50 miles west of Corpus Christi. Close to Alfred was the Orange Grove Naval Auxiliary Landing Field. Elizardo remembers the noise of aircraft disturbing what would otherwise be a peaceful, serene setting. The owner of the ranch tried to sue, but dropped the case when he became ill. He hired a health-care worker, named Alvin Lemond, to take care of him.

Elizardo believes Alvin was in his 60s at the time. About 20 years her senior, he served in World War I. Still, he and Elizardo developed a relationship, and their daughter, Diana, was born in 1961, when Elizardo was 42 years old.

Elizardo valued her independence and didn’t marry Alvin, nor accept much assistance from him. She instead turned to her family, who came through. In particular, Rosa, a younger sister, helped raise Elizardo’s daughter.

"Rosa was like another mother for Diana," Elizardo said.

Now 82, and still never having attended one day of school, Elizardo has a daughter and two grandchildren who have earned bachelor’s degrees. She says she once felt bad about never getting an education, but is glad her daughter and grandchildren have.

Changes for Latinos took place after WWII, and there is nothing wrong with being highly optimistic and wanting everything good for them that they can earn, she says.

"We had more opportunities [after WWII] for education," said Elizardo, "and today we can have even more."

Mrs. Elizardo was interviewed in Alice, Texas, on November 29, 2003, by Israel Saenz.