By Jose Araiza

While many were in shock after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, Domínick Tripodi unhesitatingly volunteered to fight terrorism abroad. The U.S. Army applauded his initiative and loyalty but denied his petition. Although a seasoned war veteran, Tripodi is 76 years old.

Tripodi's sense of patriotism began at 17 when he lied about his age to fight for his country. This patriotism continues to help him come to terms with the psychological effects of war and the subsequent challenges he currently faces.

His parents, Petro and Nancy Tripodi, emigrated from Italy and settled in a Latino East Los Angeles community known as Happy Valley, where they raised seven girls and six boys. The family was poor, so his family raised livestock to eat.

"I was in sixth grade when I got my first pair of shoes," Tripodi said. "Before then, we used to just walk around in our bare feet."

Tripodi's parents taught him to speak Italian, but he preferred to speak the Spanish of his neighborhood. From as far as he could remember, Tripodi had a fondness for the Mexican culture, a penchant that often overshadowed his own Italian heritage.

"When I would go to school, the Mexican kids would want me to trade my lunch sandwich for their tacos," Tripodi said. "I always did because I loved the tacos, and they loved my sandwiches."

On Dec. 7, 1941, when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and pulled the United States into World War II, Tripodi was 14 years old. At 16, he was ready for combat, and all that stood in his way of enlisting was his mother's signature.

"I took a petition to my mother, but she wouldn't sign it," Tripodi said. "My mother didn't think I was ready to fight in a war."

A year later, Tripodi lied about his age and enlisted. His parents knew nothing about his choice, so he decided to tell them the day he was shipped out. He was inducted on Oct. 23, 1943, at the age of 17.

Tripodi was first sent to train at Camp Roberts, Calif., for 18 weeks. On weekends, he’d hitch a ride on a local funeral home's hearse to visit his parents, paying $10 for the trip.

"I would come home on weekends, and they would still try to talk me out of the Army," Tripodi said. "But it was too late because I was already in."

In April of 1944, he headed overseas to fight for his country.

He first was shipped to Dover, England, but Tripodi wouldn’t see battle for nearly a month. He suffered from tonsillitis, so he was sent to a Scotland hospital for 18 days to recover.

Tripodi’s opportunity to see combat came when he volunteered for demolition duty, a decision that would alter his life forever, he says. The main objective of his unit, the 20th Engineer Combat Battalion, was to destroy any mines, unexploded bombs and obstacles in the way of infantry troops. His team had its orders: Land at Normandy beach and clear the way for ground troops.

"When we landed, we never did it (clear the beaches). It was all kinds of confusion, because the tide went out," Tripodi said. "The soldiers would jump out the landing craft and everyone was going straight to the bottom of the beach because they had full backpacks."

Tripodi took off his backpack and ran for the shore, negotiating corpses and fallen comrades along the way.

"You hear people screaming and hollering. You had to jump to avoid the dead bodies." He recalled. "They tell you keep moving, because you are a target out there."

Private First Class Tripodi made it to land, and for the next three weeks, he cleared mines and unexploded ordnance.

"If the Germans blew up a bridge, we used to have to build the bridges overnight with whatever means possible," Tripodi said. "Rubber, wood, metal, you name it."

Tripodi completed campaigns in France and Luxembourg. Belgium would be the last place in which he would see combat, where he helped liberate a village from German control. His team was bombarded by German artillery but kept advancing until it reached a stream.

"About 1:30 in the morning, the Germans started to shell the place. They captured us dressed in American uniforms," he said, recalling his days as a prisoner of war.

Tripodi was wounded by shrapnel and suffered a fractured shoulder, but he hid his wounds to avoid being killed. The Germans marched their captives into a house where the American captives were interviewed. He was kept in a barn with livestock and fed little. Later, the prisoners were transported by train until they reached a permanent prison in a town near the Baltic Sea.

Tripodi and 16 other captives were housed in a 16-by-16 cage with a stove and bucket for using the restroom. He was to be held captive from December of 1944 to May of 1945.

"We were only given small amounts of potatoes to eat," Tripodi said. "You could feel the lice biting your skin at night. It was such a horrible experience."

The Germans then shifted from the American front to the Russian front, leaving Tripodi and the prisoners stranded. In the Germans' absence, British troops came through the area and took an 89-pound Tripodi back to the American front. At long last, he was free.

After receiving medical attention, he was sent home, discharged on Nov. 23, 1945.

After leaving the Army, Tripodi settled in East Los Angeles and worked for a local dairy where he would meet his future wife, Evangelina, with whom he had two children.

"She was the slickest thing on two feet, and I knew I would marry her," Tripodi said.

But even back home, he’d continue to suffer from his war injuries. By 23, Tripodi would lose all of his teeth because of the extreme conditions he suffered as a prisoner of war.

Still, Tripodi enjoys sharing his story, and his patriotism has yet to fade.

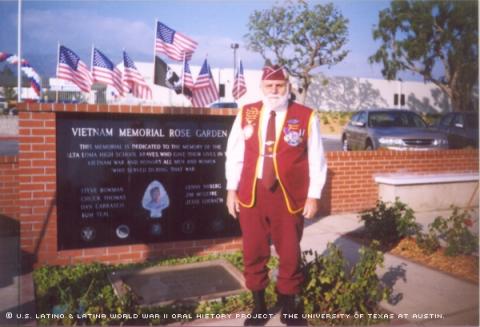

"I fly four flags: the American flag, the purple heart flag, the POW and the disabled American flag," Tripodi said. "A lot of people ask why I fly the flags for, and I say because they are my flags. I fought for them."

Mr. Tripodi was interviewed in Los Angeles, California, on March 23, 2002, by Luz Villarreal.