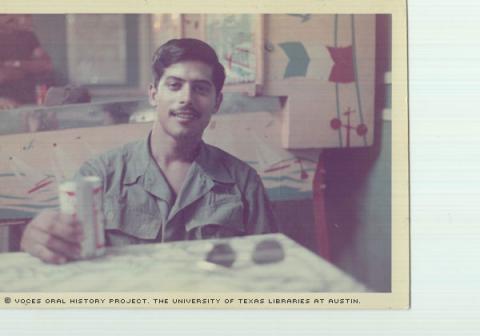

![Vietnam Vet, Eduardo Garza, was interviewed in San Antonio, Texas, on April 20, 2011. [Voces Oral History Project/Michelle J Lojewski]](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/IMG-899-05-600.jpg?itok=bRYNBIQV)

By Emily Macrander

"I'm a new man."

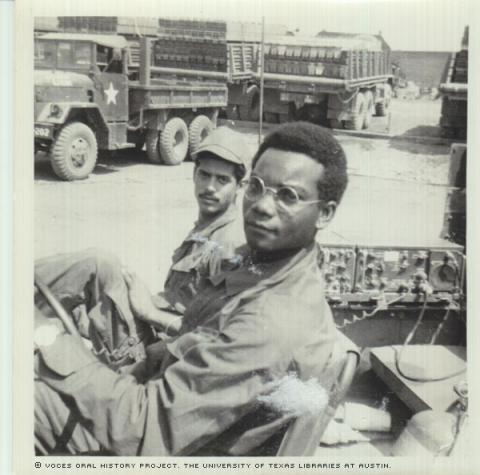

Eduardo Cavazos Garza was speaking to himself, or out loud. He wasn't sure and didn't really care. He was on a boat, floating down another South Vietnam river. It was the summer of 1969. He was in his early 20s. His life's possessions were in his army issue duffle. He was a combat engineer, trained to operate explosives, help out infantrymen and kill.

Garza was a small-town Texan. He grew up with a strong sense of home and family, shelter and belonging. His experiences growing up in El Indio, 145 miles southwest of San Antonio, and his time in Vietnam shaped his life as a warrior, activist and father. No matter what he was going through, he had faith that he could prevail and become a "new man."

In Vietnam, the land around him was beautiful and warm. The people were farmers. They worked the land, and they ate what they grew. It reminded him of his family and home.

"They had rice fields; we had cotton fields, and we had tomato fields and lettuce," Garza said.

"I realized once I was there that this was a people struggling to survive under domination from another people, who were their own people," Garza said. "'Why am I here? Why am I, as an American, not treated fairly by my own troops because of being Mexican?' My attitude was, I just want to do my time and get home. "

Garza wanted to help the children who went to his camp begging for something to eat, although he knew that some were Viet Cong spies. He said that he didn't want to attack an enemy he didn't understand. He didn't feel like he was right to be there. He said he felt like he was in their space fighting their war. But he understood that he had a commitment to the U.S. Army and he had a job, a job that he was technically good at.

Garza encountered many men willing to take a bullet or a broken bone to avoid combat in Vietnam.

"I was sitting on the bleachers on my first night in country waiting to be deployed to a unit and a young black man came up to me and asked me to break his leg," Garza said. "He says, 'Hey man jump on my leg, break my leg. I know that, if I get sent out there, I'm going to die.'

"I said 'I'm sorry. Get someone else.' "

Garza expected that he would die in Vietnam. Before his eyes, he saw soldiers change.

"Those who had suffered losses to the Viet Cong took on a hard, vicious feeling towards the Vietnamese people, whether they were [from the] south or north," Garza said. "I never went there. Even when I lost personal friends to combat, I understood that I was in a combat zone and that people die."

Garza remembered one particular mission that went badly; 13 men died, and several were wounded. They were friends who he drank with and relaxed with. He said he could remember their tattoos -- the ones their mothers didn't know about.

He smoked dope in Vietnam. He said that it helped him focus and calmed his nerves. He recalled that $10 bought a kilo of marijuana. Garza knew that some enlisted men were into harder drugs, but he avoided them.

"There were some people who hid it and some people who didn't," Garza said. "I remember we were on a river leaving a fire base, and these guys were shooting up heroin, yucky stuff. They said, 'Hey want some of that?' And I said, 'Nooo. No thank you.' I had to laugh because it looked sick. They were injecting this mud, coffee-looking stuff into their veins. I wasn't there. I wasn't into that sort of stuff."

He wrote home when he could. Regularly, Garza received letters from his sisters and mother. Occasionally he got care packages. He said tortillas didn't travel well to the jungle. Between the weeks in transit and the dusty heat, they were pretty crumbly by the time they got to him. There was also a young woman from Corpus Christi, Diane McBroom, with whom he corresponded. After the war, they were married. He said the letters connected him to the world outside the war zone.

In South Vietnam, Garza had a girlfriend. She was an indigenous woman of the Montagnard people, who were trained by U.S. Green Berets to help the South Vietnamese fight the North Vietnamese.

They started talking at his base camp. Then he began visiting her in her village. Garza traveled there with a soldier who was dating her cousin. Sometimes he spent time alone with her in her hut. He knew his time in country was growing short, and this was not a serious relationship. He said he missed seeing White girls, Latinas, and Black girls. The Rest and Recuperation vacation he took to Australia was fun. But it wasn't the U.S. It wasn't Texas.

Garza said the longer a guy spent in Vietnam, the more likely he was to question the purpose of returning to The World, a slang term used for the U.S.

"Why go back to The World, if this is all I know, military maneuver?" Garza said. "There was a phase where it wasn't important to be here or there. There was really no ambition. Maybe there are some better whores in that village. Maybe they've got some strawberry wine, some beer, some marijuana. We didn't care after a while. We just wanted to stay as safe as possible."

On boat rides, between missions, he would lay back and look at the overhanging tree limbs. He said they made him think, 'This isn't so bad.' Iguanas hung from the branches, their eyes darting every which way. Garza knew he was good at his job. He knew he had the option of extending his tour for another year. While floating down the river, he dreamed of a time when war was only a game.

It was the summer of 1960 in El Indio, and a group of 10-year-old boys played in a ditch near their homes.

"I'm a new man!" a young Eduardo Garza announced as he jumped up, a new, non-fatally injured cowboy. Just moments before, he was make-believe shot, by a boy pretending to be an Indian.

The boys were playing in the ditch along Cuevas Creek. They were far from the busy roads and stoplights of Corpus Christi. So here, by their town's main road, the boys played at war.

Things were not looking so good for the cowboys. Their dugout caves had been located, the boys were growing tired, and their only hope was that the sound of a dinner bell would lead to early peace negotiations.

El Indio had a fluctuating population. During the school year, 180 people lived in town; 80 during the summer, when many migrant farmworkers left their homes to harvest crops.

The town, which depended largely on agriculture for its economy, had a small grocery store, which also served as the local bar. There also was a cafe across the street, run by Mary Belle Smith.

"We grew watermelons, and we would give them away," Garza said. "We had so many tomatoes. And my mother canned. She canned tomatoes and corn -- canned all these different things."

The house Garza grew up in was surrounded by three acres of land on which the family grew whatever was in season. Each family member helped out. "Whenever it would be time to eat meat, I would be the one who would be sent out to slaughter rabbits, chickens, ducks, doves, turkeys," Garza said. "I also had to feed those creatures. I had a goat that I had to milk twice a day. Her udders would get so huge, she would be complaining. I'd milk the goat," he said, imitating the goat milking sounds while showing how he milked her.

Garza's father was a teacher. He taught seventh and eighth grade math, science and history. He was one of the first educators in Texas to be certified to teach special education. He also drove the school bus to the campus 19 miles northwest of El Indio.

"His job was to drive the bus from El Indio to pick up all of the students and take them to Eagle Pass schools and return them at the end of the day to El Indio," Garza said. "For that we got free housing."

The elder Garza worked hard for his place in the school system. In the 1960s, there were not many Mexican-Americans or men working in education. He constantly worked hard to go above and beyond the other professionals he worked with. So when evaluation time came around he got high marks, he kept his job and eventually got promoted to higher positions in the school district.

His mother was a craftswoman. She was known for her fine ceramics, and she crocheted for what seemed like all the time. Both parents were native Texans; he was a descendent of Apache Indians, and and her family was from the Yaqui tribe.

In El Indio, the Garza youngsters generally fit in. Although segregation was more prevalent in larger areas, Garza grew up knowing that he looked different from the majority in his town and was sometimes called names he didn't like.

"We didn't know much about segregation," Garza said. "There was some, because the dominant culture was White. There was still some racism, what you'd call racism," discrimination based on ethnicity.

"My best friend was this White kid, Roger, and we'd start an argument, and it would go straight to race. You know, he'd say 'You dirty Mexican.' And I'd say, 'Oh, you White trash.' That kind of thing was very 'lived.' "

Garza recalled those memories from different periods of his life during his interview in San Antonio during the summer of 2011.

"I'm a new man!" he said in telling the story of how he grew up in El Indio. He pretended to fall down dead, then smiled, "Just like that." He said that when he was in Vietnam he would pretend that if he got shot he could regenerate like he did in the games he played growing up.

Garza chose to not extend his tour in Vietnam after the year he spent over there. He was ready to go home, see what The World had to offer him, to be "a new man."

When her returned home from the jungle, Garza decided to marry the girlfriend he had corresponded with while he was oversees. He said that the marriage was based more on friendship than love. His new wife was a history major, and she wanted to see the world. His final deployment was to West Germany, so they both went.

In West Germany, the pair ate, drank and partied. They traveled to as many countries as they could. Once his deployment was over, the couple returned home. Garza used the GI Bill to go to college. They lived in Corpus Christi. Their marriage became troubled. Less than a year after being stateside, they split up. His wife went to Dallas, and he went to stay with his parents, who had moved to San Antonio. She was pregnant with Garza's first child, Thea Vanessa

Garza was very poor then and the relationship ended somewhat suddenly. He did what he could to see his young daughter, hitchhiking to see her in Dallas as often as he could.

His parents were surprised to see how much the years abroad had changed their son. He was angry, edgy and had trouble settling down. He said he had been "pissed off" that he had been sent to Vietnam and because of the things he had to do there. He bounced from career to career, had trouble with authority, and worked constantly to make ends meet, he said.

He didn't know at the time, but he was dealing with post-traumatic stress disorder, which was diagnosed by the Veterans' Administration 15 years after he returned from Vietnam.

He moved around Texas a lot when he returned home. During his time in Kingsville, Garza became involved in the Chicano rights movement. He became interested in studying and improving the inequities in the education of Mexican-Americans. He also became active in the Chicano political movement and joined La Raza Unida Party, which aspired to be an alternative to the Democratic and Republican parties. All the while, he used art to express his political beliefs. He played the drums and flute at rallies and performed in street theater displays.

In his second and third marriages, Garza had four more children, Lucina Sanchez Garza, Adriana Maru Sanchez Garza, Saul Adan Sanchez Garza and Sofia Luisa Greimel Garza. He was very close with the children from his second and third marriages and aimed to be the type of father that his father was: Someone who was not afraid to say, "I love you. I am proud of you."

He worked for the Veteran Administration hospital for 23 years and then retired. His first job with the VA was to be an escort. He ran errands for the doctors and nurses and wheeled dead bodies to the morgue. Garza used the time with the dead veterans to bless their bodies. Late at night, the walk down the hallway to the morgue was dark and quiet, with nothing but the sound of the gurney wheels.

Later in life, Garza joined Celebration Circle, a nondenominational worship group. He continued to work toward peace within and in The World. On some nights, he couldn't sleep because of the nightmares from Vietnam. He stayed awake meditating, watching the dreams go by, and waiting for them to be over.

Garza was always drawn to create art: paintings, poems, and theater works. He was a part-time film actor and was involved in the San Antonio Arts scene. In 2006, Garza started the Jazz Poets Society in San Antonio. Every week, the group held writing sessions, followed by band-accompanied reading sessions. At the time of his interview, he was still leading the Jazz Poets Society and was a prolific writer and musician.

He said that he no longer wanted to be "a new man." He was at peace working on the man he was on that particular day, at that moment in the universe. He offered one bit of advice, "Take time to know what you want.

"What is it you want?"

Mr. Garza was interviewed by Emily Macrander in San Antonio on April 20, 2011.