By Fernando Dovalina

Even though he stands only five feet five, Ed Peniche must be one of the tallest men in the world. Every time this son of Mexico has been challenged in life, he has measured up – and then some.

He measured up as a soldier fighting for his adopted country, the United States, in World War II, although he wasn’t yet a citizen. He was wounded in action, and he saved the lives of fellow soldiers by endangering his own. His heroism earned him a handful of medals, including the Purple Heart and two Bronze Stars.

He says that, though he highly values the medals extolling his valor, his most prized possession is a simple citation from Central Virginia Community College, which mentions his 22 years of service to the college as a professor and calls him an inspiration and an influence to several generations of students. Finally, it bestows on him the title of professor emeritus.

"Once you have the education," he said, "that opens the doors everywhere."

He pointed to his war decorations and said, "I received those in the midst of destruction and hate and despair."

Then he grabbed the framed resolution of appreciation and said, "This one I achieved by sticking to goals I established."

Peniche was one of eight children of parents who grew up during the Mexican Revolution. Neither of them went much further than the seventh grade. But they were self-taught: His father was an avid reader and wrote poetry. His mother insisted her children get an education.

Peniche remembered his father reading to his children, as well as making them pore through Mexican newspapers, especially the Sunday editions, with their editorials and articles that dealt with the arts and literature. In school, he was exposed to English, and in the parish church's Saturday catechism classes, to Latin.

Progreso, on the Gulf of Mexico coast, is about 25 miles north of Merida, Yucatan's capital, a larger, more cosmopolitan city, which offered the Peniches multiple reasons to visit, such as stores, parks and the zoo.

On Dec. 7, 1942, at the age of 17, Peniche arrived in the U.S. to get an education and live in Paducah, Ky., with his father's sister, Aunt Pilar, and her husband, Eduardo Menendez. It was clear, however, that he was going to have to start almost from scratch in Paducah, as the schools didn’t recognize any of his credits from Mexico. He attended both junior high and high school at the same time, beginning in January of 1943.

In April, Peniche received a letter from the draft board, notifying him that even though he wasn’t a citizen, he was subject to the draft and had to register by his 18th birthday. And in May, Uncle Sam notified him that he’d be inducted. He decided to volunteer for the Army Air Corps instead.

"I wanted to be a fighter pilot. They had a program for high school students ... you could go either Navy or Air Force pilot program, so I went to take that program. I passed everything ... but I didn't finish the written portion. I was not that fluent in English."

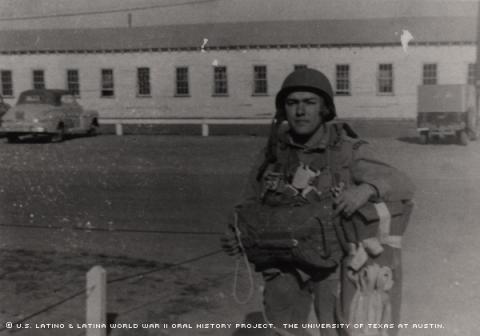

In September of 1943, he became a U.S. soldier, receiving basic training in the field artillery, then getting advanced training to be a part of a Forward Observer Team. He also trained in hand-to-hand combat.

To Peniche, that meant eventual assignment to Europe.

He was right. In early May, he arrived in Bristol, England, and almost immediately was given a chance to apply for airborne training. It was an easy decision, he said. By the time the Army took out an allotment for his mother, money for GI insurance, the old soldiers home and laundry, he had $16 a month.

"So they say ... 'You jump out of airplanes, and you get $50 a month jump pay.' Well, $50 a month jump pay and you wear a suit like that. I go for it," he said, laughing at the recollection.

He was initially assigned to the 101st Division Artillery, a part of the combat support elements (and replacements), to be deployed with the follow-up seaborne echelon and to provide security and logistical support to Division Artillery units.

On June 6, 1944, D-Day, the Allied invasion of Normandy was launched.

"We departed on the 5th, in the afternoon. And there were lots of ships," he said. "And the next day, around 10 o'clock, we heard announcements that under the command of Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Allied forces were landing on the coast of France. Now, at that time, we ... knew we were going to go to France."

But the men didn't know which beach. Then the unit received its maps and final briefing.

"It was ... a little bit misty ... the ship was crowded and some people were getting seasick. I wasn't," he recalled.

Peniche, in fact, said he was excited. He and the other men were combat support troops, not assault troops, and they were headed for Utah Beach, bringing heavy equipment, artillery, supplies, ammunition, tractors and trucks for the troops in battle.

But the naval task force had gone in the wrong direction and suddenly, he said, "Omaha Beach was in front of us, about 15 miles."

The correction took another two days, so, on June 9, "D plus three at 7 p.m., we landed in France at Utah Beach."

And that's when he saw the first dead troops, first Germans, "but then I also, I saw an American soldier, young soldier, big, big guy, probably over 6 foot, had a neck wound, and he had bled to death."

"That was very scary," he said. "I saw dead Germans, 11 of them. I saw cows, bloated, horses, a lot of this stuff. You knew you were in combat."

Peniche came under artillery fire in the vicinity of Carentan.

"In all sincerity, you don't have time to fear. You assume ... that you will not be hit. But somebody else will. But it's terrifying ... cause you know it's a false self-assurance."

But, he said, when a shell goes by, "you feel the heat or you smell the thing ... But you are in denial, and you are hugging the ground. You're doing everything you were trained to do."

Peniche started his airborne glider and jump training once he returned to England in the middle of July 1944. He’d been assigned to Charlie Battery, 81st Antitank Antiaircraft Airborne Battalion, a special unit to support infantry regiments.

On Sept. 15, orders were issued for the mission Operation Market Garden, which began on Sept. 17, and "turned out to be the largest airborne operation. They lifted altogether 35,000 men."

Eighty-seven gliders from his battalion left, and "47 made it to the landing zone," Peniche said. The ones that didn’t were shot down or lost in the English Channel or Belgium.

Peniche's glider left on the 19th and landed "in the middle of the German army," he said.

"As we were getting the gun out and waiting for the Jeep, we came under enemy fire ... Holland is a very flat country. So whenever you are on a road in Holland, you are a target."

The glider had landed at the Drop Zone/Landing Zone near Zon.

"We were sent to protect the bridges. Our mission was to keep the highway ... open, so that the British armor would flow into northern Holland."

The First British Airborne Division, however, had landed "in the middle of where two Panzer divisions were re-outfitting." The British were defeated.

"But we, the 101st and 82d, we accomplished our mission,” Peniche said.

"There's a saying," he added, "'There is nothing taller than a short paratrooper.' I feel 10 feet tall. You know why? Because I had confidence, and I felt welcome."

At the time, Peniche says, he was "five feet five, 132 pounds. I would jump number 4 and number 18 would beat me to the ground."

But what counts, he said, is "Do you measure up? Can you measure up? Can you give all you have? Can you stand tall? ... Can you go all the way? All these are icons, you might say, icon words. But you live up to it because you reach down deep ... We were not Supermen. Of course, we were not. I saw the troopers dead. That's not Supermen. I know, I know that times, I remember, the crying, in pain. So it's not Supermen. Humans – willing to go that extra mile – that's what it was."

On Dec. 16, 1944, the German army attacked the Allies "with a quarter of a million men, 1,200 tanks, about 3,000 guns," Peniche said. "And the Allied front lines started crumbling."

Adolf Hitler, believing that a crushing blow to the Allied armies on the western front would free his armies to fight the Russians on the east, had bet everything on this attack.

The Battle of the Bulge was on.

Bastogne, in the Luxembourg province in southeast Belgium, was an important highway and railroad junction; control of Bastogne was essential to both sides. On Dec. 17, in the evening, the 101st Airborne Division, a strategic reserve that had been refitting at Reims, in northeast France, was called into combat at Bastogne, about 100 miles away. The Germans' Fifth Panzer Army was only 15 miles from the town the morning of Dec. 18.

But the Americans had driven all night, reaching Bastogne just ahead of the Germans. Against tremendous odds, the men of the 101st stood firm. Their military achievement came to be known as the Defense of Bastogne.

"Here we are, surrounded by eight German divisions," Peniche said. "And they demand that we surrender."

Gen. A.C. McAuliffe, commanding the 101st, responded with a one-word answer that became famous and re-energized Americans on the war front and the home front: "NUTS!"

Peniche theorized that McAuliffe knew "he had the men to back him up."

The Germans intentionally took advantage of the weather to protect their offensive. Mist and rain made it difficult for the Allies to attack from the air. But the weather took its toll on both sides as temperatures fell.

"I am from the Yucatan. To be ten below zero, my biggest fear was that I was not going to wake up. The enemy fire -- the enemy fire would not let up. But the cold was torturing you day and night. And I, I was panic-stricken ... If I fall asleep, I'll never wake up."

Foxholes didn’t provide much protection.

"It was snowing. We had, in some places, two feet of snow. And then, when you are in the foxhole and the heat, your body heat, melts all that snow. So in the bottom of the foxhole, you have a puddle of water," water that threatened their lives.

The men would place hay at the bottom of the foxhole to give their feet some protection from the melting snow, but frostbite claimed many soldiers.

"I saw some German prisoners. They were purple, their faces, their arms. And Americans that died of frostbite."

On Dec. 26, Gen. George Patton's 3d Army relieved Bastogne, but the worst wasn’t over for the 101st. On Jan. 3, 1945, it had its heaviest engagement yet, just north of Bastogne in Longchamp, Belgium.

"The Germans attacked our front. They had 32 tanks, two regiments ... our battalion was in the center."

The Ninth Panzer Division "pulverized the front lines. It was the most -- the heaviest artillery barrage and airbursts," Peniche recalled.

"The attack lasted about three hours. We destroyed three tanks. Another squad ... destroyed seven tanks. That was a major contribution that we made to break the backbone of the attack."

Peniche, his squad leader and a close friend would be wounded, Peniche's shrapnel wound to his knee joint requiring the work of a specialist. Later, he was cited for "heroic achievement in action," awarded the Bronze Star with V device for "valor."

In July of 1999, the people of Longchamp erected and unveiled a monument to the men who defended the town. Peniche and his family attended, and were awed to find out the rock on which the monument stands was named in his honor. It’s called the Stele Peniche.

"Garner told me in a letter, 'I'll never forget when you exposed yourself to save me ... You showed me what a great Mexican-American you are.' He spelled it out like that. And O'Toole wrote me a letter saying, 'I always told my children that there was this little Mexican boy you could count on when you needed him the most.' "

Peniche spent two and a half months in the hospital. After that, he rejoined his unit in Germany. The war in Europe ended in May of 1945, and Peniche expected to be sent to the Pacific, where the war against Japan raged on.

"But then, Truman, who knew what he was doing, didn't hesitate in dropping the atomic bomb and sav[ing] about half a million Americans from their deaths."

He's quick to add that his position wasn’t anti-Japanese. He’d never used racist terminology, such as "Japs, Krauts," he said.

After the war, Peniche returned to Mexico and helped the country organize its Airborne units. He resigned his commission as a lieutenant in the Mexican army and returned to the U.S. in early 1952 to re-enter the U.S. Army.

Peniche was sent to Fort Riley, Kan., for a basic training refresher course and, to Fort Benning, Ga., for a refresher course in Airborne training. To improve his English so he could finally get a high school diploma, he began corresponding with students at his former high school in Paducah.

One of them was special. Her name was Dean.

"I thought she was -- she just was a wonderful and gentle girl."

In May of 1953, Peniche graduated with Dean and her twin brother. Soon thereafter, he was offered a job to instruct the Taiwanese in the use of American weapons. That meant a two-year stint abroad. He decided to formalize his relationship with Dean.

"So I went to Paducah and I asked her parents," he said. "I asked for her hand in marriage. Very formally. And of course we spent three hours ... in her living room. You know, she [was] 18."

Peniche was 27.

"The parents had several concerns. I was older. I was a soldier. What did I have to offer? I was Catholic, Mexican, you know. They didn't say Mexican, but it was in their minds ... I don't blame them. I mean, an 18-year-old girl." Despite initial misgivings, the Baggetts approved the union. And on Oct. 6, 1953, Ed Peniche and Deanie Baggett married in her house, and soon thereafter left for Taiwan, where they spent two years. In Taiwan, he learned Portuguese from a priest. On their return, Peniche attended the University of Georgia. The Army selected him for an assignment in Vietnam and trained him in the Vietnamese language. He arrived in Vietnam in January of 1959. Deanie joined him in May. They were there until July of 1962.

Because of his language skills, Peniche landed a job with the InterAmerican Defense College in Washington, D.C. While there, he enrolled at Georgetown University, later switching to George Washington University because it was less expensive. It took him 11 years, but he earned his undergraduate degree in 1966. Then, in1969, he earned a degree in history from the University of Nebraska in Omaha. A month after leaving the service a second time, in 1970, he enrolled in graduate school at Murray State University. Eighteen months later, he defended a master's thesis on Mayan culture and civilization -- the civilization of his Yucatan homeland and Mayan ancestors -- and received his master's degree.

"That allowed me to become a college professor."

But even that wasn’t easy. He applied to 127 colleges, receiving 122 rejections and five maybes.

"And then I went to Central Virginia Community College and when they interviewed me for Spanish, the president told me 'I cannot give you credit for what you taught in the military.' "But the college gave him a one-year offer, after which Peniche would get a second look from the administration. He stayed 22 years.

As of 2005, Peniche was semi-retired and continued volunteer tutorial work for ESL and U.S. history. He was also in the process of writing his memoir, in which he would highlight the values of higher education. He also lectured in the Houston metropolitan area about once every other month. In his lifetime, he learned and utilized five languages in the military: Spanish, English, French, Portuguese and Vietnamese.

He and Deanie had three sons. One of them died at 19, a tragedy that Peniche admits almost destroyed him.

Peniche also admits to having no patience for people who claim to be patriotic by waving the American flag in front of them as proof.

"You know, many people identify themselves with, they use the flag for many things. But I don't accept that from those that are phonies, because when it came to defending the flag, I was in front of it, defending it," he said.

"That's when you defend the flag. You don't defend it from behind. You get in front of it to really defend it. And that's what I did."

Mr. Peniche was interviewed in Kingswood, Texas, on May 17, 2000, by Fernando Dovalina.