By Manesh Upadhyaya

Watching war movies about battle ships as a child in Beeville, Texas, created a yearning in Elias Chapa to enlist in the Navy.

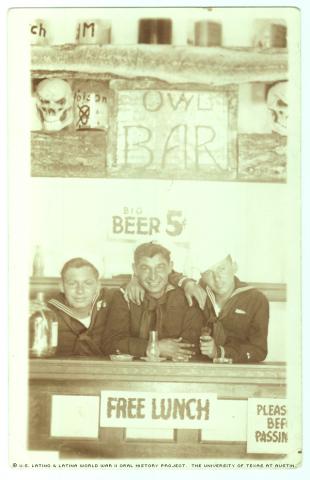

At the age of 17, Chapa still wasn’t old enough to sign up for the Navy. Having three older brothers already in the military, however, it wasn’t hard for him to see what he wanted to do after high school. He waited a year for his 18th birthday, and then enlisted in the Navy on Feb. 5, 1943. Along with close Beeville friend Ray Salazar, Chapa began his career in the United States Navy.

Chapa traveled from Beeville, located 180 miles south of Austin, Texas, to San Diego, Calif., for 13 weeks of basic training. He also spent some time in San Diego attending Group III Mechanist Mate School.

After graduating, he went aboard the USS Rathburne, a four-stacker, four-boiler room ship, which was never used in World War I but took part in World War II. The Rathburne was an older destroyer that also served as a reconnaissance vessel on the Pacific Front.

Two of the boiler rooms were removed to house “Frog Men.” These men specialized in swimming and demolitions.

“They would blow up coral reefs and do whatever they had to do to make it easier for the invasion to come in,” Chapa said.

The ship went from island to island all over the Northwest and South Pacific, including the Solomon Islands, Palau and Okinawa.

The U.S. was sending its task force north to penetrate the Japanese defense in the Central Philippines to achieve access to Tokyo. The last mission the ship took part in was traveling to the Philippines with “a main task force of about 800 ships,” Chapa said. This fleet followed a typhoon for three days and three nights, so the Japanese had no idea where it was. The rough seas caused a boat to capsize because “it couldn’t handle the 40-degree roll or pitch,” Chapa said.

By the time the storm cleared, all of the ships were off the coast of the Philippines in a confrontation with the Japanese. The Japanese Imperial Navy sent out cruisers and destroyers. The Rathburne’s duty was to protect the bigger ships from torpedoes.

Chapa remembers one particular ship hit by an enemy torpedo:

“The Honolulu was listing at about 48 or 49 degrees and we towed it out of the main battle to safety and went back into battle.”

Japanese aircraft filled the sky, trying to get their Kamikaze planes as close as they could to American boats.

“The General Quarters sounded, which meant battle time,” Chapa said.

Being a fireman, he left the fire-room station and ascended to the 20-mm gun. A gunner, loader and sight-setter all had to man the weapon. Chapa was the sight-setter.

As a sight-setter, his duty required the aid of a gyro compass.

“I had to judge the distance the airplane was coming in. The height, the elevation, the deflection was automatic, hence the name the gyro compass,” Chapa said.

The loader’s last name was Lopez. According to Chapa, the loader had the worst job.

Each magazine contained 120 rounds leading to a barrel Lopez had to change. He had to take the barrel off, as well as put another magazine on in the middle of battle.

“They were luck[y] that time they didn’t get hit,” Chapa recalled.

Chapa says his team downed four Japanese planes that day. After battle, the sailors picked up dead pilots and brought them on board to check their pockets for belongings. According to Chapa, the Japanese believed that when they died, they’d go to heaven, so they brought keepsakes with them.

“They had letters to their parents, playing cards, condoms and little mementos and pictures,” he said.

After acquiring the objects and information needed from the fallen pilots, the Navy would “wrap them up, put a weight on them and drop them off in the ocean,” Chapa said.

When asked what was done with the dead men’s possessions and information, Chapa replied, “They were given to Washington or something,” and that he “did not know exactly how that ended.”

Recalling what feeling scared was like during battle, Chapa said, “It’s so sudden, you don’t have time to be scared. The only reason I knew I was scared was because my knees were bumping.

“Next day is just another day, waiting for another airplane to come by.”

Life on a Navy ship wasn’t always about shooting planes and attacking ships. Among other diversions, Chapa played bingo. He was the person who called the bingo numbers and got paid “10 cents for about four hours.” Chapa said bingo “helped him with stress.”

After being honorably discharged from the Navy as a fireman first class on, according to his discharge papers, Feb. 21, 1946, or, according to Chapa, Feb.26, 1946, he worked as a mechanic at his older brother Nick Chapa’s garage. Five years later, he owned his own restaurant and gasoline station, Cozy Lounge.

Chapa now resides in his Beeville home with his wife, Teresa O. Chapa. At age 84, he’s the youngest and last living of his 10 other siblings. He had six brothers, three of whom were enlisted in the military, and four sisters.

Elias Chapa was interviewed in Beeville, Texas, on March 21, 2009, by Denise Morales.