By Kimberly Tilley

On the walls of a small, comfortable East Austin residence, family photographs fill the house. A framed photo of a beaming couple sits on the mantle, and an adjacent bedroom contains a small altar with a photo, surrounded by a crucifix and several candles, of a young man with long black hair and soulful eyes. On the handcrafted bookcase, more photographs of happy faces adorn the shelves.

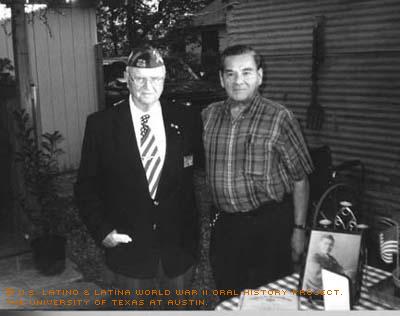

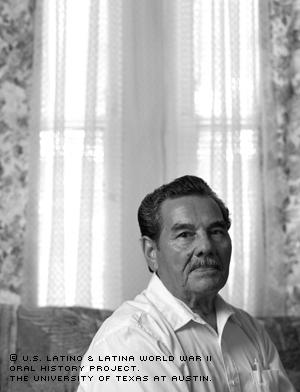

Seventy-six-year-old Eliceo Lopez says his faith in God and love for his family have been constants in a life filled with everything from farming in Central Texas to surviving two bouts of malaria in the South Pacific during WWII.

Lopez stands 5-feet 7-inches tall, and has expressive brown eyes that crinkle around the corners when he smiles. He smiles often. Sometimes, however, especially when talking about his youth and his war experiences, his eyes cloud over and twitch ever so slightly.

Lopez grew up on a farm in Ganado, Texas, about 15 miles outside of Victoria. The middle child in a family of 13, he was raised by the strict, but loving, hand of his father Esteban Lopez and the watchful eye of his mother Otilia Galbert Lopez, both Mexican American immigrants. Despite its size, Lopez said his family always had plenty to eat.

"We raised our own cattle, we raised a lot of vegetables," he recalled. "Sometimes I think that a lot of people would be better off in the country now, than in town, 'cause every time we turn around, you have to take your hand out of your pocket to pay for something," he added.

Most of the Lopez children's time was divided between helping with the 100-acre farm and attending White Hall School, a building that served the first through 12th grades. Whenever they had free time, the children would go to the movies, listen to western music or organize a Sunday baseball game.

Overall, Lopez remembered a quiet farming life in Ganado, growing cotton, corn, vegetables and feed for 10 head of cattle, 16 horses, hogs and chickens. He also recalled, however, a divide between the Anglo and Mexican American communities.

"We had a few problems, especially in school," Lopez said. "Not the teachers," but rather kids going home in bunches and starting trouble.

"There was quite a few of us, and quite a few of them," he recalled.

Sometimes, fights would break out between the two groups. Lopez would return home with a black eye, only to be disciplined with a stern lecture and a good spanking from his father.

"I think my daddy taught me a lot of things," said Lopez of the advice his father would give him: “Stay out of trouble and don't do nothing wrong, or I'll spank you."

"He was a good man."

The pivotal moment in Lopez's young life came when his father died of a brain tumor in 1941, at which point Lopez was forced to leave the 10th grade and help his older brother run the family farm.

"I was only 15 when he passed away," Lopez recalled. "He always wanted me to finish school. And I quit on him because I had to."

Lopez helped run the farm for three years after his father's death; however, he was drafted in 1943 into the United States Army and forced to leave his family.

"When they draft you, you don't go 'cause you want to. … You go because they take you. And so there went the farm," said Lopez, referring to the fact that the family had no option but to lease the land after he was drafted.

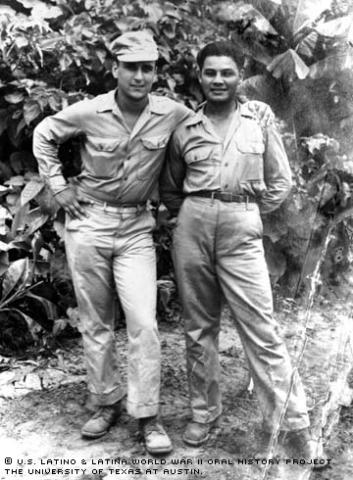

On Sept. 13, 1943, Lopez was inducted into the Army and sent for basic training to Camp Fannin in Tyler, Texas. A short six months later, he was on board a ship loaded with 4,000 other GIs, headed to Guadalcanal to fight in the South Pacific jungle.

"I never heard of Guadalcanal, I never heard of New Caledonia," Lopez said. "I never heard of none of those places."

Lopez was a mortar-crewman member of the Company I, 305th Infantry. They landed first at Guadalcanal, shortly after the initial invasion in late 1943. From there, they headed to various other battlefronts in the South Pacific, encountering the heaviest resistance in Cube City and Bougainville.

"I slept about halfway scared all the time," he said. "I was always, always homesick. It's a real experience and I was just lucky to make it home."

After the war was over, Lopez was one of the few members of his division to be sent to Japan. He was transferred to a unit called the Wildcat Division to serve in the military police. Many of the men had accumulated enough points for time served to be sent back home, but Lopez found himself in Tokyo among the ruins left behind by U.S. bombers.

"You could just see nothing but concrete and steel rods sticking out of the ground, he said. "There wasn't much left of Tokyo."

From Tokyo, Lopez went to northern Japan, where the cold temperature was in sharp contrast to the humid heat of the South Pacific jungle. Although the war was over, the danger wasn’t; the GIs had to go everywhere in groups.

"Lots of guys got ambushed and killed, even after the war," he said.

Lopez also remembered being apprehensive about the food served in restaurants, partly because he was afraid someone might poison him and partly because he couldn't maneuver the chopsticks.

"They give you those little sticks to eat with. I almost starved. … I could never get it right. Those things, they'd slip one way and another,” he recalled. “I said, ‘Oh, forget it. Give me a fork!’"

When the order finally came to go home, Lopez was overjoyed.

"I wanted to come home, study and eat them good tortillas again," he said. "I only weighed 162 pounds when I got out of the service … and within about six months, I went up to 180 pounds. Eating good, eating good!"

While Lopez was overseas, his family had relocated to Austin. Upon his return, he started vocational school under the GI Bill, studying for 18 months to be a radio technician. He had the opportunity to study television, but by that time, he’d already met his wife Vera, whose maiden name was also Lopez.

"I guess you might say it was love at first sight," he said. "When we married in '47, she was 17. Everybody thought I'd robbed the cradle!"

"We've been married now going on 53 years."

The couple had three children: two daughters, Rosa and Linda, and a son, Robert, who died from lung cancer.

Looking back, Lopez credited the influence of his father and family, coupled with a strong faith and equally strong work ethic, with making him the man he is today.

To the young people of today, he offered his own words of wisdom.

"Don't say things that might offend someone," he said, adding, "Don't abuse your body, don't abuse anybody."

Perhaps the most important piece of advice Lopez had to offer was, "Life is good, you just gotta learn how to live it."

Mr. Lopez was interviewed in Austin, Texas, on February 26, 2001, by Kimberly Tilley.