By Henry Mendoza

That his Purple Heart came in the mail long after he was home probably says the most about Eloy Baca's tenure as a soldier in the United States Army and, for that matter, the way most Latino veterans approached World War II -- it was something that had to be done so they gave it their best in a simple, straightforward manner.

For Baca, like his fellow veterans, that was quite a lot.

Sitting on his couch in Rio Rancho, N.M., Baca recalls stories and moments from WWII as if he were re-living a movie. He talks about being amid the smell of death, watching a friend's limb fly by like the whistling noise of a bomb overhead and clearing bodies from a bloody beach in a calm matter-of-fact way.

Baca recalls leaving his native Mosquero, N.M., to enlist with a cousin and a buddy in Las Vegas, N.M.

"I decided, 'let's see what's going on.'

"They were an influence to me because they were the ones who suggested I go with them and they were older than myself," Baca said.

All he’d known in his 18 years of life was ranching and riding horses in the tiny town of Mosquero, about 100 miles from the Texas Panhandle in northeastern New Mexico.

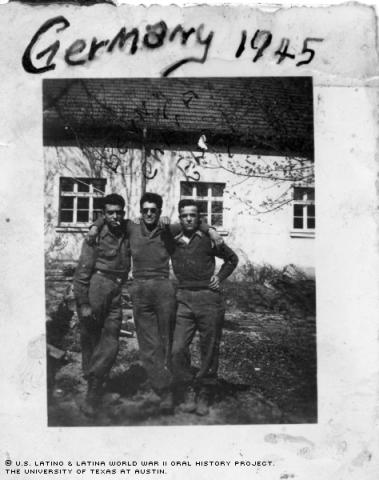

"We did a lot of training (in the Army) . . . my training was demolition work, mines and booby traps," he said. The Army then taught him about building bridges so he would know how to destroy them. Baca served in Africa, Sicily, Italy, France and Germany with Company C of the 120th Engineer Combat Battalion, supporting the 45th Infantry Division.

"We landed in Oran, North Africa, on June 22, 1943. We just assembled there, we didn't do any training. From there, we made the invasion of Sicily on July 10, 1943. From there, all the way up to Germany," he said.

"We made an assault landing in Sicily," Baca recalled. "I remember the water was so rough. I think they were 20-foot waves. It was really bad, really bad."

"They bombarded that beach for about an hour before we landed. I remember they threw those nets over the troop ships . . . but you had to be very careful, unless you get smashed," he said.

"We hit the beach there . . . because they had barbed wire entanglements all over the beach. In fact, we'd go ahead of the Infantry. We were the first troops that hit the beach to blow the wire, you know," he said. "So when you hit that beach, you didn't know what was ahead of you. Our job was to blow that barbed wire. It was very scary."

Baca said what seemed like days passed as the assault landing continued, but it was really one long day later when an officer came up to him.

"He told us, 'You and you and you, you come back with us on the truck.' And what we had to do is pick up dead GIs from the battlefield and bring them back. And I did that for about a week," he said. "You know, in July in Sicily, it's hot hot. The bodies decompose very easily. And I'm telling you, it was so rough there. It's the worst smell you can smell. I couldn't eat for about a week."

Baca paused and reflected for a moment, thinking about how some memories disappear, others remain vivid and some are repressed and emerge once the conversation begins.

"I remember we were running and I'd seen guys running and they stumbled. It looked like they were stumbling, but they didn't stumble, they were shot, you see," said Baca turning away, his voice cracking with emotion.

"But you know, when you're a unit, like you feel kind of safe, you're a unit. There's a lot of people with you. It's not really that bad. You think having all these people with you you're much safer," Baca said. "It's like a family."

He participated in the initial amphibious assault in Italy, at Salerno, on Sept. 20, 1943, and against Anzio on Jan. 22, 1944. That battle memory reminds him of Anzio and heavy German artillery.

"You could hear it fire and then you could hear it like a freight train coming," he said. "If you hear that artillery piece, it probably went through. The one that's going to hit you you're not going to hear it," he said.

Baca recalled landing in France at Ste. Maxime on August 15, 1944; he then fought north to join the troops from Normandy.

"That's when we went to this town in France called Epinal, France, from the 22nd through the 25th of September in 1944. And they sent three of us to the mountains to erect some roadblocks ... blow some heavy timber on the mountain roads so the German tanks couldn't go through. That's when I got hurt.

"What you do is go up the mountain and blow so many trees on the road so the enemy can't come though in trucks or tanks. We were putting this TNT necklace around the tree and put a fuse on it ... my buddies were down below," he said.

"And I was doing that and I slipped on the snow. And the detonator went off on my back, pretty close. I was given first aid by an infantry medic. I was hurt real bad, a few cuts, but mostly blast."

After a few weeks of rehabilitation, Baca returned to his unit, achy but nonetheless ready for battle. He was injured again, however, during an advance against German forces across the Danube River on April 26, 1945.

"I remember my boat went over and I had to discard my rifle and get out. I remember helmets floating by. And I got hit by mortar shells on both legs and here on the head," he said, pointing to a battle scar. "That's when I got wounded the second time."

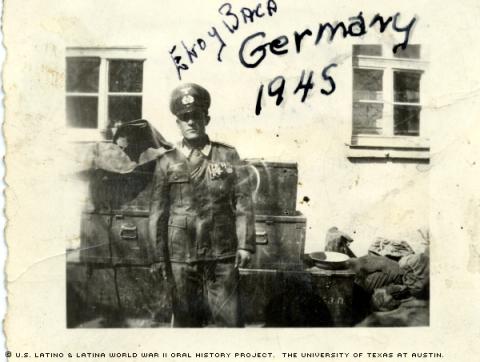

"I [always] thought maybe I was going to make it," said Baca, who was discharged July 15, 1945. He earned a Purple Heart, the AEME Campaign Medal with four amphibious landing arrowhead devices and several bronze campaign stars, and the WW II Victory Medal

Every once in a while, he’ll wear his WWII cap with the Purple Heart on it and he’ll be stopped by a young Chicano who will say to him, "Thank you for what you did. I'm proud of you," said Baca with a smile.

"We were good soldiers," he said.

Like many veterans, Baca used his Army experience to get an education, working on a business degree at Abilene Business College, knowledge he’d use later at his liquor store. Baca married Flora Montaño on Jan. 1, 1948. The couple had seven children: Herman, Rita, Dolores, Thomas, Kathy, Nicholas, and Paul.

Mr. Baca was interviewed in Rio Rancho, New Mexico, on January 24, 2002, by Brian Lucero.