By Nikki Muñoz

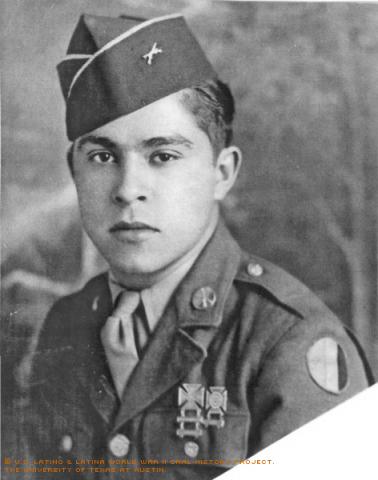

Before he reached the age of 22, Ernesto Pedregón Martinez had already worked as a painter of bullfighting posters, helped liberate a Nazi concentration camp and returned home to start a new life, which would eventually lead to his becoming a nationally known artist.

Martinez was born in El Paso, Texas, in 1926 to a hardworking tailor and a mother who was a homemaker. Martinez proved to be a survivor: All six babies his mother bore died at birth before he was born.

Martinez grew up in El Paso and lived very close to the border of Mexico. Some of his earliest childhood memories are of accounts of bootleggers smuggling alcohol across the river during Prohibition, and of him and his neighbors sitting around a radio listening to boxing matches. Martinez said radios were scarce, so a local furniture store that owned one would bring it into the middle of the street and let everyone hear the Joe Louis fights.

In 1940, Martinez began Cathedral High School, which was a Catholic school. He was able to attend the private school because he was an altar boy at the church and his father was allowed to pay a discounted tuition of between $2 and $4 a month.

During high school, Martinez's interests included dancing, sports and ROTC, but his true love was painting and drawing. He became interested in bullfights and attended many in Juarez, Mexico. At 17, he began creating posters to promote the bullfights.

Martinez graduated from high school in 1944 and was eager to join the military.

"My biggest worry in high school was the war would be over by the time I got there," he said. "They call it the innocence of youth because you don't realize what you're asking for. ... It's no picnic."

Because many of his friends were older and had become paratroopers, Martinez also wanted to be a paratrooper. However, because of a broken collarbone from a few years back, he didn’t make it. Three months after graduating, in September of 1944, Martinez enlisted in the U.S. Army. His basic training was in Missouri, and he ultimately ended up on the European front.

He entered combat in January of 1945. The first time he and his fellow soldiers heard gunfire as they approached the front lines, they didn't recognize it.

"We were so innocent at the time, we thought it was a rainstorm." Martinez said.

Outside a church in Belgium, he remembers seeing bodies being laid in the snow with only a blanket covering them. Martinez said he and the other soldiers wondered if no room was left inside, forcing people to be put outside.

"It did not register that they were already dead," he said.

Martinez and the 104th Infantry Division, a highly decorated unit known as "the Timberwolves," needed to cross the Rhine River, but most of the bridges across it had already been destroyed by the Germans. The Rhine, which was a formidable obstacle, was already being invaded by the Germans. Martinez remembers Gen. George S. Patton's 3rd Army luckily finding an intact bridge. The Germans had failed to destroy it, and, despite their efforts, it survived until a bridgehead could be established. Martinez's division crossed the Rhine at Bad Honnef on March 21-22, 1945. They advanced across the Ruhr Basin and met the Soviet Army at Pretzsch on April 26, 1945.

While in Germany, the group came across a compound with barbed wire surrounding it. Figuring it was a prison, they began tearing their way in and found many barracks. Inside, they discovered thousands of people who looked like skeletons. The infantry had come across the Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp in Nordhausen.

"It was an awful sight. Some of them must have weighed 80 pounds," Martinez said. "People cried and hugged us.

He added, "There were piles of dead bodies inside the barracks."

Martinez had been in the Army for less than a year when he learned that the war was over and Germany had surrendered.

"I did not believe the war was over until I saw American jeeps drive by without machine guns," he said.

Martinez returned to New York on July 3, 1945, then went on to Camp San Luis Obispo, Calif., for two months to prepare for the invasion of Japan. Soon after, the atomic bomb was dropped, and the invasion was canceled.

Martinez left the service with the rank of corporal. He earned a combat infantry badge, a Bronze Star, a World War II victory medal, good conduct medals and a European ribbon with two battle stars for fighting in major campaigns -- Rhineland and Central Europe army of occupation.

Martinez went back to El Paso and attended International Business College, where he met Mary Trejo, who would become his wife. The couple had five children.

For a time, Martinez was employed at Fort Bliss, working on tabulating machines and big cameras that followed missiles. He also worked as an illustrator/artist for magazines.

When he was 48, MEChA (Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán), a group involved in Chicano issues, gave him the opportunity to put on his first art exhibit. The turnout was remarkable, and his career as an artist was launched. Martinez went from selling paintings for $10 to $300.

During the Chicano Movement, his name and art began getting recognition. He did work for many activists in the movement, including Cesar Chavez, an activist for the rights of migrant workers. He also did work for Corky Gonzales and Reies Tijerina, who were both active in the movement, as well as developed friendships with them.

Martinez believes his big break came when he was invited to be a guest on "Siempre En Domingo," a show in Mexico City that is broadcast all over the United States and Mexico. He also painted a mural called "Meso America" at Bowie High School in El Paso, which gained recognition from the mayor and the media.

More recently, Martinez has given many talks and has lectured at the Holocaust Museum. He said he believes it’s important to speak out about his experiences. Other accomplishments include being named a Texas State Artist, making him the first El Paso native to receive that honor. On Oct. 26, 2001, Martinez was inducted into the El Paso Artists' Hall of Fame. Throughout everything, he has stayed strong and dedicated to helping his community through his story and art.

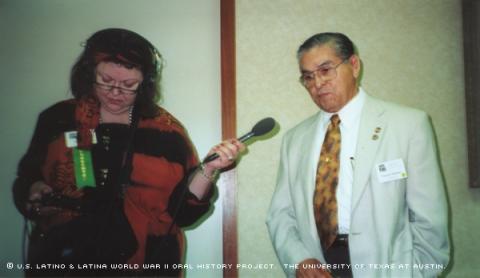

Martinez was interviewed in El Paso, Texas, on June 28, 2001, by Jeffrey Lee Johnson.