By Grant Abston

After his graduation from Abraham Lincoln High School in Denver in 1969, Ernesto Torres developed a hobby -- racing cars.

Torres, who registered for the draft after graduation, had trouble finding steady work after getting his diploma. Although he worked part time at the Columbine Country Club in high school, the draft affected his job search.

"I had trouble finding jobs because the first thing they asked was your draft number," Torres said, referring to his number -- 137 -- which he said was considered low. "A lot of people wouldn't hire you because they were afraid you'd get drafted. It was a hard time finding a decent job."

However, it was racing cars that pushed Torres to accept and even embrace his future in the military.

"I was always messing around with cars and racing," Torres said. "When I got drafted, I was on the verge of losing my driver's license. I thought, 'Well if I didn't go what am I going to do? Because I won't have a license anymore.' "

He discussed his military options with his uncle, Bill Medina, and came to terms with the likelihood that he would be drafted to fight in the Vietnam War. Torres reported to a military station when his draft number was called, but he opted to enlist in the Army to gain benefits he would otherwise not have received as a draftee. As an enlisted man, he thought he would have more opportunities for advanced training.

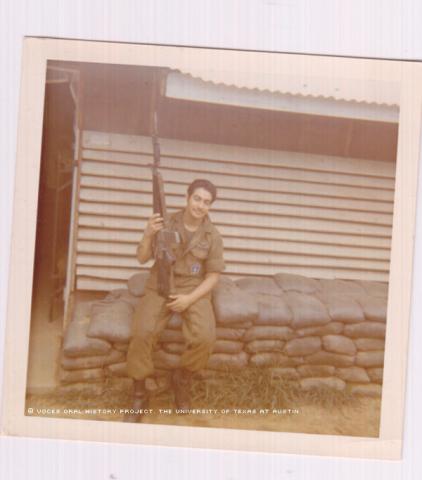

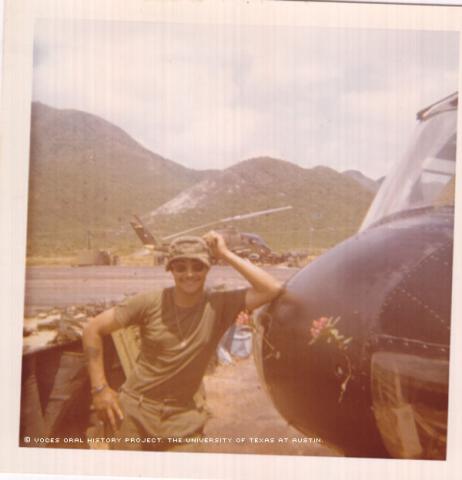

Torres was inducted into the Army on June 5, 1970. He spent eight weeks at Fort Leonard Wood, Mo., before going to Fort Rucker, Ala., to complete special helicopter training. After watching a movie at basic training on helicopter gunners, he put that title down as his fourth option in the Army. He had listed turbine engine maintenance, avionics-radio, and air frame (aircraft mechanic) as his top three options.

However, because of a shortage of helicopter door gunners, Torres was selected to become a gunner and spent three weeks training for the job of basic helicopter maintenance. He had scored well in an aptitude test.

"When I got to Door Gunner School, I knew they didn't need those in Germany and in the states," Torres said. "I knew I was going to Vietnam. I was excited about it, but at the same time hoping I would make it back in one piece. I thought that this was my opportunity to show what type of person I was."

He wanted to prove who he was to his family and to himself.

Torres arrived in Vietnam in December 1970 and spent the next 12 months in an assault helicopter, completing missions throughout Vietnam and on the borders of Laos and Cambodia. He was assigned to the 61st Aviation Company (Assault Support Helicopter), 1st Aviation Brigade. He participated in about 50 combat missions during his 12-month tour of duty, but his first mission remained one of his most vivid memories.

"We were searching for a fixed-wing aircraft that disappeared," Torres said. "The pilot said, 'Hey, if you see something, let me know.'

"So I said I saw something, and the pilot made a 90-degree turn," he said. In training, Torres had been accustomed to smooth gradual changes in direction. But this abrupt movement left him all but hanging out of the chopper.

"Well, they didn't do that in training," he said. "So the first time scared the [crap] out of me!"

While Torres viewed his military duties as necessary work to achieve the United States' overall goal in North and South Vietnam, it was TV news and various newspaper articles about the war that opened his eyes. Torres could not believe how strongly people back home opposed the war.

"My experience did not change my feelings [about the war]," Torres said. "I think it did make me more aware of how much public resentment there was toward the war. I remember when I was in Vietnam, we could see the demonstrations. And that's when I realized how unpopular the war was, but it didn't change my feelings."

He returned to the U.S. in December 1971, arriving at Fort Lewis, Wash. Torres remembered a certain incident soon after he emerged from the plane.

"At the airport, while I was washing my hands, an older gentlemen came up to me and started poking me in the chest and asked, 'Did you get these for killing babies?' " Torres said the man was pointing to his ribbons. "It shocked me. I just walked away; said nothing."

As Torres realized how deeply his own friends opposed the war, he hid the fact that he had served proudly.

"They would ask, 'Well why were you there?' " Torres said. "I didn't mention I was a Vietnam [veteran] because I wasn't interested in creating conflict. Unless somebody asked, I didn't openly come out and say I was a Vietnam [veteran]. I was real surprised the public was that strong against the war."

He said he didn't quite understand the politics of it all, or the history of the war.

"I wasn't sure of the validity [of the war] -- just know that my number was called. It was time to serve my country," Torres said.

Torres was honorably discharged from the military in February 1972 as a Specialist E-4. His decorations included the National Defense Service Medal, the Vietnam Service Medal, the Vietnam Campaign Medal and the Air Medal with a V Device.

Upon his return, he started working for IBM, first in typewriter repair for the office products division, then as a customer service engineer, and later in processing equipment and data processing. He retired as an IT support specialist after 30 years.

He was married and divorce, and had two daughters.

Although he faced scrutiny as a Vietnam veteran upon his arrival to the United States after the war, Torres knew things had changed. He was proud as the public sentiment toward veterans of that war improved during the following decades.

"It's a lot more accepted now and people are willing to talk about it. You feel like people appreciate it," Torres said. "I'm proud to say I served my country."

Mr. Torres was interviewed by Ricardo LaFore in Denver on Aug. 9, 2010.