By Lindsay Graham

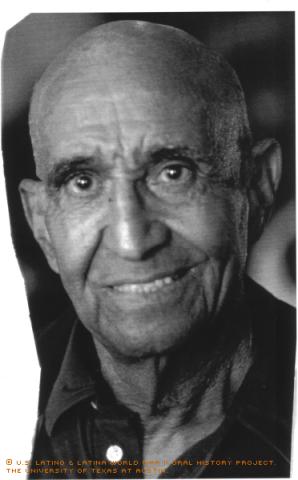

Raised in Ybor City, a Cuban neighborhood inside Tampa, Fla., Evelio Grillo attended black segregated schools and grew up with black role models.

"Black Cubans were closer to black Americans and white Cubans were closer to white Americans," Grillo said. "We became culturally African American."

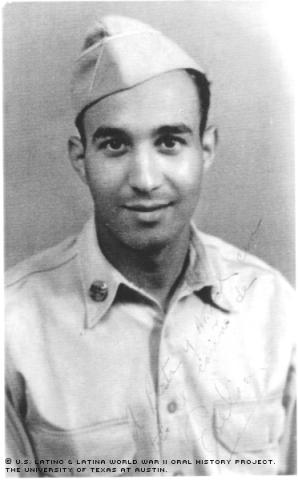

He went on to attend Dunbar High, an all-black high school in Washington, D.C., and attended Xavier University, a college for black students in New Orleans, La. He then was drafted into the Army to serve in a "colored" unit in the China-Burma-India Theater.

Those three years in the military reinforced Grillo's perception of himself as an African American. The experience also nurtured his desire to serve as an activist later in life, volunteering with many organizations including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the Negro Political Action Association and the Mexican-American Political Association.

"I was indoctrinated just by being part of the society, to be black American," he said. "So, I have a hybrid identity that can't be torn apart."

Grillo wrote about some of his experiences in a book published by Arte Publico Press: "Black Cuban, Black American."

As part of the 823rd Engineer Aviation Battalion (Colored), Grillo and the other black troops were subjected to inferior conditions. White troops on board the U.S.S Santa Paula, which was transporting them to India, used fresh water, while African Americans used salt water. White troops had access to the deck during their off time, while black troops were forced to stay in the crowded bow. Meals were segregated.

During the voyage, the black men wrote and signed a petition to the commanding officer of the battalion, complaining and asking for better conditions. The commanding officer responded that no discrimination had taken place. Still, Grillo wrote in his book, there was a sense of accomplishment to have stood up and protested.

Later, in India, the poor treatment continued: The "colored" troops slept in tents on the bare ground, which became muddy during the monsoon season, while white officers slept on raised bamboo pallets, Grillo said.

It wasn't until after World War II that the military was desegregated. During the war, black troops were often reserved for tasks such as building roads.

"We were just like slaves and slave masters," said Grillo, noting the officers in charge of black troops were white.

Grillo's basic training was conducted at Fort George G. Meade in Maryland in June of 1941 and at MacDill Field in Florida. Grillo's battalion then set sail for India, arriving in July of 1942, where they maintained air bases until February of 1943, when they were given the task that would occupy them for the next two years -- building the Ledo Road.

Stretching from India into Burma, the Ledo Road joined the Burma Road at Myitkyina, Burma.

It proved to be a daunting undertaking.

"By the time we had achieved our objective, the war was over," Grillo said.

Building the road wasn’t the only thing that occupied Grillo's time, however. It was while he was in India that he began a mission that would help him find his calling in life.

"The time came when I was appointed the recreation and morale sergeant," he said. "I was assigned a Jeep and was told 'Here, do what you want and tell me where to sign.'"

Grillo's new duty engulfed much of his free time, an advantage considering how little action the men saw.

"We were bombed twice by Japanese planes," he said. "The planes would fight in the air, and one of them would get hit and would go down in flames, but that was like a movie. It didn't ever affect me so that I had bomb fragments to worry about."

Without the worry of battle, Grillo concentrated on devising new programs, such as a volunteer jazz band. Grillo used his new, on-loan Jeep to drive to base headquarters and pick up drums, a saxophone, a trumpet, guitars and a trombone.

He also published, for two years, The Hairy Ears Herald, a daily newspaper named for the nickname they gave engineers.

"We just wanted to know how many more Germans we had to shoot," said Grillo with a laugh. He added that the information in The Hairy Ears Herald's stories came via radio broadcasts: a group of men would take notes from the broadcasts and then write up the news. The Herald was mimeographed and widely distributed.

Although Grillo spent much of his time in India publishing the newspaper, as well as building a baseball diamond and a movie theater, he says he never recognized it as something he wanted to do with his life.

It was his decision to build a basketball court that helped convince the sergeant of what his life's work should be.

As the units within Grillo's vicinity formed a basketball league with eight teams, the basketball court prospered. Before the war, many of the players had enjoyed college careers in the sport.

Although hundreds and sometimes even thousands of spectators would come to watch the games, it was another aspect of the league matches that Grillo admired: For the first time, white and black troops were integrated in one program in India.

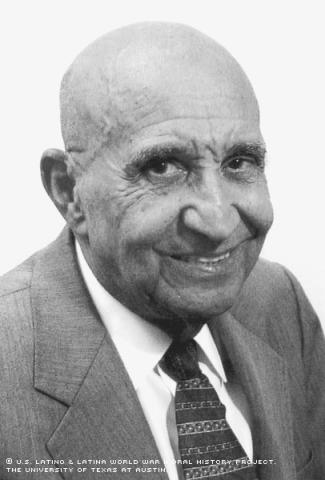

"I saw myself as a possible bridge between English-speaking and Spanish-speaking people, but especially between English- and Spanish-speaking blacks," he said.

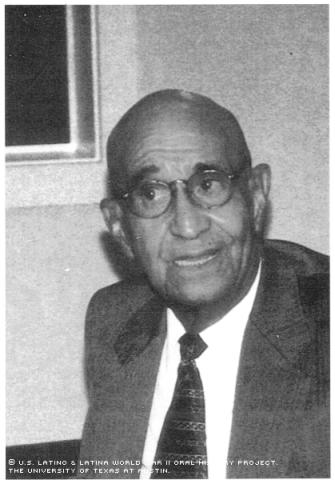

Grillo returned stateside in January of 1945, and was discharged from the Army in September; he’d attained the rank of Staff Sergeant. Grillo then moved to Oakland, Calif., where he served as the director of Alexander Community Center, a center for blacks and Mexicans.

For two years, he promoted interaction among blacks and Mexicans, bringing together school principals, social workers, probation and parole officers, nurses, police officers and other professionals to discuss their concerns, plans and objectives. Grillo also attended weekly seminars led by Gertrude Wilson, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley School of Social Welfare.

After his service at the center, Grillo entered the university on a fellowship and graduated with a Master of Social Welfare degree in 1953.

Following his graduation and a stint as a social-group worker and teacher at Contra Costa County Juvenile Hall, Grillo returned to Oakland to work as a community relations consultant. He was eventually hired as the first black employee of the city manager's office. He also worked for the Carter Administration from early 1977 until late 1979 as an executive assistant for Policy Development in the Department of Health, Education and Welfare.

While in these positions, Grillo had the opportunity to help integrate citizens that came from different backgrounds, heritages and ethnicities, and help end the segregation he’d seen since childhood.

Working in Oakland gave Grillo the opportunity to help other people see themselves as more than simply black or white, American or a hybrid, he says. It gave him the opportunity to help people see themselves as members of both communities, as he sees himself.

Mr. Grillo was interviewed in Oakland, California, on January 26, 2003, by Mario Barrera.