By Joshua Carniewski

Felipe Rangel was in the Korean War, was wounded, and lived to tell the tale. His memory isn't the best, but it's not because of the battle wounds.

Rangel was born in 1931 in Topeka, Kansas, and his childhood was like those of many others in the 1930's. He had seven brothers and six sisters, and he loved riding his bicycle and playing with his friends and brothers on the neighborhood street corners.

The part of his childhood that wasn't normal was that he was run over, twice. It happened once by a milk wagon and once by a car. "I tried to get on the wagon, and I missed a step and fell underneath," Rangel said. "The other time I was on an errand, and I tried to cross the street to watch a baseball game and a car got me. That's how I got run over that time."

In fact, he probably came as close to death then as he was when he was wounded in the war. "They didn't think after the accident that I was even going to make it," he said. "Due to the fact that I got run over, I had a lot of head damage."

The head injuries he suffered during these two accidents affected his memory. He dropped out of schools after the eighth grade. "School was a little hard for me because of the accident I had," Rangel said.

Rangel went to work for the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway with his father and four of his brothers. His family was no stranger to war. Four of his brothers served in World War II, and two of them were killed in the war.

Rangel was not old enough to serve during WW II, but when Korea began in 1950, he knew he was going to be drafted. He tried to get out of going to war by asking for a deferment.

"I tried to get a deferment because of the two brothers we lost during WWII, but when my youngest brother got a deferment I knew I had no choice but to go," Rangel said.

Rangel said he did not speak about war with anyone in his family. He admitted that he did not keep up with the news and was not a political type of person. Those factors made matters much harder when he got drafted, he noted. "Sooner or later the draft was going to get you," said Rangel.

Rangel, 21 at the time he was drafted, left for training in San Diego in May of 1952. "Training was the hardest thing I had ever done," Rangel said.

Rangel was originally in the 26th draft, but because of an injury he had at Camp Pendleton, he was held back with the 27th draft.

Once he was in Korea, Rangel recalled days "in the back," meaning when he was not on the front lines, as being sort of relaxed. He was given one hot meal a day, swapped stories with his living mates, and wrote letters when he could.

The front lines were a totally different story. "You didn't get much of anything while you were up there," he said.

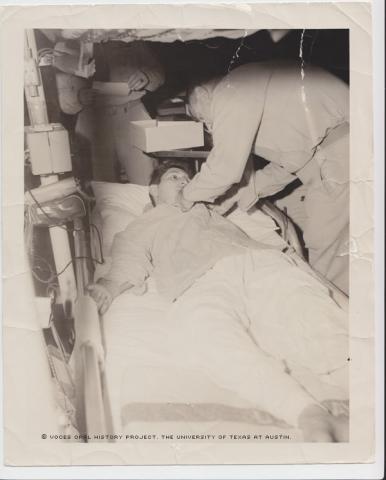

Rangel, who was a rifleman, recalled in vivid detail the night in 1953 when he was wounded. He was manning a machine gun because the man operating it before him got killed, and that's when an explosion blew him backwards and was hit with many shards of debris. His legs were most affected, along with a bad wound above his right eye. He managed to walk a little ways but then collapsed and became unconscious.

"I was taken by helicopter to a medical ship," Rangel said. "The medical care was great." He was on the ship long enough to get the necessary medical care, moved to another ship, and taken home.

He admitted that the combat was scary.

Rangel was awarded a Purple Heart, as well as the Korean Service Medal, the United Nations Service Medal and the National Defense Service Medal. "The medals remind me of the memories and the good friends I made, and that I was lucky to have survived," Range said. He held the rank of Private First Class when he was discharged.

Rangel was married his wife, Mary, in 1954 and they had had five children. After the war he worked at different jobs before taking a job at the veterans' hospital, which he held for 29 years. After retirement he continued to live with his wife in Topeka.

Rangel said he thought the war was good for Latinos and for himself, but while he was there, race it did not play a large role. It was the fight for the U.S.A. that was the focus. "You were just another body in battle. Race didn't matter," Rangel said. "I knew I had to go defend my country."

Mr. Rangel was interviewed by Joseph Schuetz on June 16, 2010, in Topeka, Kansas.