By Mary Mejia

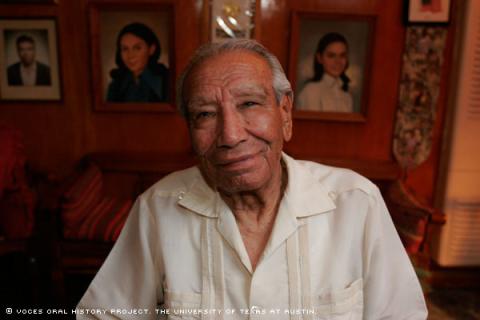

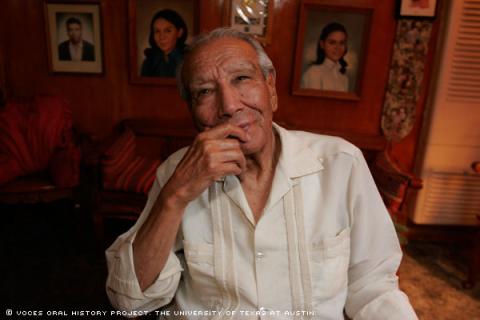

Felipe T. Roybal decided in June 1940 to help out his family financially and unwittingly began a military career that spanned more than 30 years.

Roybal's parents, Vicente and Isidra Roybal, were among the founding families of Las Cruces, New Mexico, the town where he was born. Before the Great Depression, his father and uncle owned a grocery store that brought in enough revenue to allow Roybal's mother to stay at home and raise Roybal, his two brothers and a sister.

"We played around. Baseball, softball, whatever," he said.

But once the U.S. economy was devastated by the Depression, everything changed, and 17-year-old Roybal saw the Army as his only employment option. He was a graduate of Las Cruces High School.

Roybal enlisted by lying to a recruiter in adding a year to his real age and saying he was 18.

"They didn't question you. All the recruiters wanted to get in their quota," Roybal said.

His inaugural journey away from home was to Fort MacArthur, in San Pedro, Calif., where he put on a military uniform for the first time. He was soon trained to use rifles and other weapons.

Looking back on his service, Roybal said he was never discriminated against, even though he was the only Mexican-American in his unit. He did recall, however, seeing young men from South Texas fighting with minorities in the barracks.

"There was always a fight," said Roybal, adding that people in Los Angeles would host boxing matches on Main Street during weekends and would call Fort MacArthur for volunteers.

At least four or five soldiers, including himself, were willing to fight for an extra $5 to $10, said Roybal, adding that it wasn't as crazy as it sounds, considering soldiers were getting paid $21 per month. That was decent money at the time, but Roybal only kept $6 of his paycheck, sending the rest back home to his family.

Roybal said he broke his nose, jammed his head and lost some hearing during the course of his brief Los Angeles boxing career, which came to an end when he was sent to Alaska. On Dec. 7, 1941, Roybal recalled his first sergeant running into the showers yelling, "Go back to your barracks, put your cold-weather suits on and go to your alternate positions! Take your weapons! Pearl Harbor has been bombed!"

Nobody in his unit had heard of Pearl Harbor, so they initially thought it was a joke, Roybal said.

Roybal volunteered to join the 82nd Airborne so he could get out of Alaska. He was sent to Fort Benning, Ga., for general Airborne training, and then to Fort Bragg, N.C., for additional training for the 82nd Airborne Division, The first two weeks were basic training, he said, and on the third week, jump training took place. He started learning how to pack and use his parachute and began jumping from a 34-foot tower, landing in sand or dust.

"You have to look into the horizon. Don't look down," said Roybal of how to properly land.

After the tower, he recalled completing two river jumps and two forest jumps during the day, then one at night.

"It was tough. Physical training from 5 a.m. to 5 p.m.," Roybal said.

When he completed the training, Roybal was sent to Europe and was soon landing in German villages.

"Men landed in villages and so forth. And we couldn't find them, so we started looking for them until we started finding 20 men here, 20 men there and 30 men there," Roybal said, slouching down in his chair and putting his hand over his head, disturbed by his memories of Germany.

He and his unit would pass by prison camps and convoys near Neuburg, Germany, but Roybal said nobody was allowed inside.

"It was awful. I saw them [corpses] hanging by the trees. There were skeletons," he said as he described why the stench of dead bodies and disease floated through the air near the camps.

"We were young. We didn't want to see those things," he said.

They would travel at night and sleep when and wherever they got exhausted. Sometimes they would wake up in a cemetery.

"There were people dead all around us. [The coffins] half open, half closed," Roybal said.

Roybal was discharged in 1945. Among the awards he received were Parachute Wings, the Combat Infantry Badge, the European Command Badge, Merit Award and a Purple Heart. He returned to Las Cruces and on June 15, 1948, married Bertha Morales, whom he had known since childhood. He recalled how she used to throw his textbooks out the classroom window to tease him and flirt.

He also began attending classes at Texas Western College in El Paso, Texas. It is now the University of Texas at El Paso.

He had a hard time finding a job in 1948, so he re-enlisted in the Army. He was one of five soldiers from his company who were sent to Maryland for intelligence training.

"It goes on your record, and when they need somebody, they look at your records. ' Oh, well this man has been in intelligence, they need so many men up there.' And so, poom, they send you there," he said.

Roybal was sent to fight in the Korean War with the 2nd Infantry Division in 1950 for 17 months. For several months, he was held as a prisoner of war by Chinese troops, but managed to escape. He said he couldn't talk to his family, but at least he could financially support them; they received his paycheck every month.

When Roybal returned to the States from South Korea, he was sent to Honduras. He took his family with him. He said that his career had benefitted from his intelligence training, but that it put him and his family at risk. For example, he recalled having two maids escort his daughters to and from the bus stop before and after school for their safety.

"It was very dangerous," Roybal said.

One problem was that Salvadoran Indians had occupied five miles of Honduras' border with El Salvador and declared war. American families were almost sent home, his daughter Patricia Roybal-Caballero recalled.

"We learned drills at school -- if they shot or bombed -- learned how to hide under our desks. They stopped our school bus," said Roybal-Caballero, who recalled the conflict being short, lasting a summer.

In 1954, the entire Roybal family went to Europe. Patricia finished school, taught in French, and the family traveled together every time Roybal took leave.

"They [the military] used to tell us, 'Go take a leave. Go to different countries. Enjoy yourself while you can.' So that's what we did," Roybal said.

In 1969, Roybal found himself posted to South Vietnam, a less pleasant situation.

"I was in the Special Forces," Roybal said, referring to the unit known as the Green Berets.

His memories about Vietnam seemed disappointing to him.

"We had a lot of trouble with our own soldiers in Vietnam. I stayed a week in Da Nang. It was filthy, drunks. Dope floating there like nothing. Colonels all doped up," Roybal said.

When a soldier in Quang Tri shot and killed a first sergeant, Roybal said he was unwillingly promoted to that rank. He had no choice, he said; those were the orders. His job was to protect Marines from getting shot when exiting from helicopters.

Roybal chuckled when recalling how, during his service in Southeast Asia, Patricia was attending the University of Colorado and protesting the Vietnam War.

He shrugged as he mentioned the worst welcome-back greeting he ever experienced: 200 to 300 students and civilians protesting when his plane landed at the airport in Seattle. When he and other soldiers filed out, the protesters called them killers and threw tomatoes and eggs at them.

"We had to back up and reload the plane. The plane had to go around, and we had to come in through the warehouse entrances ... From there on, I lost hope," he said looking down.

Roybal ended his military career in 1975, at the rank of first sergeant. He received his associate's degree from El Paso Community College soon after retiring. Then he returned to Texas Western College and started to study business administration before changing to liberal arts.

"It became too hard for me," he said with a laugh, "too much economics."

Although Roybal completed three years of college, he said he got sick while obtaining his degree and was unable to graduate.

His advice to future generations: "Go to school. Get educated. Lay off of alcohol."

Mr. Roybal was interviewed by Raquel C. Garza in El Paso, Texas, on May 9, 2008.