By David Zavala

Negotiating a minefield on a snowy day in World War II Germany, 1945, Felix Treviño encountered a young German soldier who looked no older than a teenager; he was leaning against a tree, one leg gone from the thigh down, the wound still bleeding.

With bullets still being fired in the area, Treviño’s compassion moved him to help the German. He reached to his side and pulled out the morphine shot issued to soldiers for pain in case of being wounded, and offered it to the German, who shook his head in refusal. Treviño then lit up a cigarette and offered it to him, but the German spit in his face. The youth knew nothing about Treviño or who he was, but he did know he was an American, the enemy.

Back in his hometown of San Antonio, Texas, Treviño wasn’t always perceived as an American. As a result, he experienced discrimination, which was common among Mexican Americans at the time. What makes Treviño story different, however, is that the closed doors of discrimination led to him opening other doors of opportunity in business and politics.

Treviño graduated from Lanier High School in San Antonio and served as an apprentice to a printer. A trained typesetter, he answered an ad in the paper placed by a local printing company. When Treviño showed up, a man told him the company didn't hire Mexicans, and shut the door.

Treviño angrily went home and thought about returning later to punch out the man that had shut the door on him. His father, Juan, arrived home from working at his market and noticed his son was upset. He calmed Treviño down and talked him out of beating the man up, suggesting instead that he start his own printing business, which he would try to help Treviño finance. The two went to look for printing equipment at a shop. When they couldn't afford the $400 required for the business equipment, the shop's owner kindly made him a special loan offer of $10 a month to purchase the machinery; delivery was the following day.

Treviño opened Treviño Printing Co. in 1938 and enjoyed some success. He married Alicia Pina in 1941 and started a family. His daughter, Margarita, was born in 1941, and Felix Jr. in 1943. While his printing business was successful, providing for a family proved difficult when the war started. National paper rationing proved detrimental to Treviño’s business: The company didn’t do well financially because of the limit on production. He decided to take a job with the Kelly Air Force Base printing department, to make ends meet.

After working for a while, Treviño became upset when he felt he was continually being passed over for raises because he was Mexican American. He gave his boss an ultimatum; if he wasn’t given a raise by next payday, he was quitting. The boss told Treviño quitting was a bad idea. Unbeknownst to Treviño, his boss had been signing his draft exemption papers for months.

The next payday came, and no raise. Treviño stayed true to his word and quit.

"Sure enough, the next day I got a [draft] letter," he said.

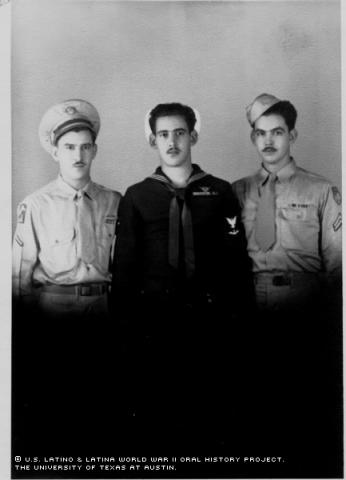

Treviño already had three brothers serving in the war.

"My father advised me that I was no obliged to go since my brothers were already serving," recalled Treviño, to which he responded, "Do you think I can be in the same room with my brothers when they return, knowing that I did not go?" His father advised him to do what he thought was right.

On Aug. 14, 1944, Treviño was shipped off to Camp Fannin in Tyler, Texas, leaving his wife and two children in San Antonio. After a few weeks of training, he was shipped to an already established Normandy beachhead. He served in the U.S. Army's Company E, 274th Infantry Regiment, 70th Infantry Division Squad, which fought in Marseille, France, from Dec. 10 to Dec. 15, 1944. Among battles fought, Treviño took part in the capture of the German cities of Forbach (Feb. 18, 1945), Stiring, Wendel (March 6 1945) and Saarbruecken (March 19, 1945), as well as the crossing of the Saar River.

Treviño served in Europe until the Nazi forces were defeated. He was on a boat to Japan when he heard the news the war was over. He was honorably discharged on Feb. 28, 1946, at the rank of Private First Class, having earned the European Theatre of Operations medal.

Treviño was invigorated upon his return. He received a degree from Southwest Texas University and reopened Treviño Printing Co. Alicia gave birth to their third child, Imelda, in 1948.

He became active in the community.

"I had always seen many people being mistreated, and my idea was that I wanted to help those people," he said.

Some of his community activities included teaching citizenship classes, teaching English to Mexican immigrants, starting a Federal Credit Union for parishioners of the poorest church in San Antonio and later contributing to the organization of the Continental Federal Bank at IH-10 and Hildebrand in San Antonio.

In the mid-1960s, San Antonio civic leaders approached the then 45-year-old Treviño and proposed he run for city council. He accepted the bid and won the election. He served on the San Antonio City Council for four years, two of which he served as Mayor pro-tem, before resigning to once again focus on his business. Treviño is known for improvements and progress made to San Antonio's once-neglected West Side.

Treviño has also served as president of the Pan American Optimist Club, president of the board of directors of the Tejano Music Awards and vice-president of the National Municipal League of Cities.

Mr. Treviño was interviewed in San Antonio, Texas, on October 13, 2001, by David Zavala.