By Avery Bradshaw, Cal State Fullerton

When Fernando Del Rio left Los Angeles in September 1950 and joined a Navy air squadron, it was the first time he had ever been away from home. Turning on the radio, he was surprised to hear Japanese music.

"We knew we were off the coast of Japan," Del Rio said.

Del Rio explained that in high school, he had watched his two elder brothers, Jose and Octavio, return home after serving in World War II. He remembers an overall patriotic feeling in America at the time. He was among the many who enlisted after WWII.

"It was what you did. I remember the patriotism," he said.

The youngest of four children, Del Rio spent his childhood in south Los Angeles. He was the son of Jose Del Rio, a mechanic with Ford Motor Co., and Juanita Palacio, a homemaker. Both of his parents were born in Mexico.

He attended Alexander Hamilton High School, which he described as a very good school. At that time, it was mostly white.

"I grew up in a white part of Los Angeles. Once I graduated, the neighborhood quickly turned black and Hispanic. But growing up, I was surrounded by white people."

Del Rio said he did not experience much discrimination in his white neighborhood. With his light complexion and Protestant traditions, he fit in easily.

"I was only subjected to racism once in my childhood that I remember. I was trying to join a boys church group, and they told me that they did not want any blacks or Chicanos joining them. That was pretty hurtful."

Del Rio was not involved in much at school until his senior year, when he developed his love of writing. He joined the senior writing club and also became absorbed in other things such as football, track and band.

"Back then there was not as much to do. We went to the library, the movies on the weekend, and the beach," he said.

Del Rio graduated from high school in January of 1950. The previous summer, he had attended Navy boot camp but returned to school to get his diploma.

When Del Rio graduated, the Navy did not need anyone. Del Rio decided to work at Hughes Aircraft Co. as a mechanic for nine months. After North Korea invaded South Korea, he was called to Seattle for training in September 1950.

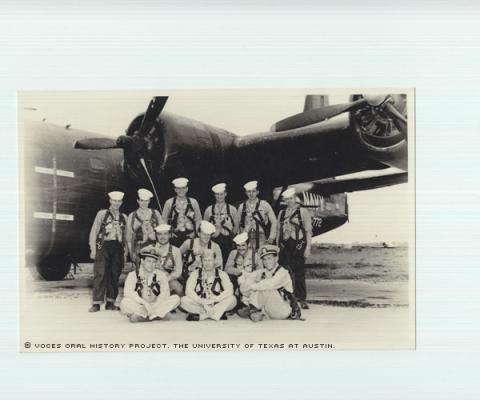

During his first assignment in Japan, Del Rio spent 11 hours a day on a plane with three other men. They looked below for unknown or suspicious boats and submarines and dropped sensors that would help identify what type of vessel it was. He completed 17 combat missions but never once fired a weapon.

After his first assignment, Del Rio returned to Seattle to continue his mechanical career. He wanted to enlist again despite the warnings of others.

"There is a saying in the Navy: 'The worst land duty is better than the best sea duty.' And unfortunately, they were exactly right."

On his second assignment, Del Rio was stationed on the USS Princeton, where he fueled and defueled planes. He arose earlier than everyone and went to sleep long after others. He described how supplies ran low on the ships and how the drinking and showering water would sometimes contain salt.

By the time Del Rio's second assignment ended and he returned home in 1953, he said enthusiasm for heroes and patriots no longer existed.

"When WWII ended, people were screaming and shouting for veterans. If you were a vet for Korea, there was not the same applause. That heroism did not exist in Korea. I did not even tell anyone I was a Korean veteran. I wanted to leave all that behind me and get my degree. That was all that mattered to me."

He took advantage of the GI Bill and fulfilled his lifelong dream of going to a university. He attended UCLA from 1953 to 1957. He graduated with a degree in international relations and went on to graduate school in the American Institute for Foreign Trade (now Thunderbird School of Global Management), in Arizona.

In the following years, Del Rio had a career in communication. He was a reporter and presenter with KCAL-TV, was the director of communication for the Southern California Association of Governments, and eventually opened his own public relations firm, called DOME Enterprises.

Del Rio developed a love of travel and attributed that to his mother, who never got to leave Los Angeles but "traveled" through her British novels.

"The most traumatic part was leaving home, but now that is all I do," he said.

Mr. Del Rio was interviewed by George Sanchez-Tello in Los Angeles on June 9, 2010.

Disclaimer: The Voces Oral History Project attempts to secure review of all written stories from interview subjects or family members. However, we were unable to secure that review for this story. We will accept corrections from the interview subject or designated family members - contact voces@utexas.edu.