By Joan Vinson

Politics in small-town Texas were very different when Frances Luna was young. Back in the days of the poll tax, politicians would offer to cover the fee to encourage local residents to vote for them.

Luna said that when she was 15 years old, Johnny Phillips, a county commissioner in Fort Bend County, paid the poll tax for her father, Elias Rodriguez. But it took more than that to earn the support of the Mexican-born cotton farmer.

"But there again Daddy was very wise," Luna said. "There were some people that he didn't care for. He didn't just vote because that guy paid his poll tax. He happened to be a good guy, so he voted for him. But he was very careful who he voted for."

Growing up in an era when Mexican Americans had to fight for their participation in politics, Luna went on to become a local activist.

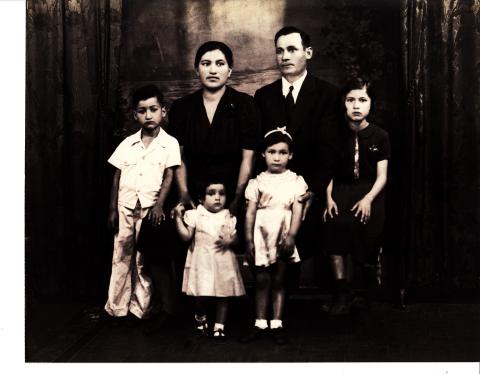

Frances Rodriguez Luna was born on April 10, 1937, in Booth, Texas, about 30 miles southwest of Houston. Her father, Elias Rodriguez, was a Mexican-born farmer and her mother, Frances Rodriguez, worked at a laundry cleaning business.

Luna's father was a hard worker who required the same work ethic from his children. After Luna and her siblings got home from school, they worked the fields. Luna said her parents expected their children to graduate from high school, a feat that all but one of the children accomplished.

In Booth, she attended a one-room school. She said the grades were divided up in rows of chairs; the first grade in one row, the second grade in another, and so on. The family moved to another Texan town, Hungerford, before moving to Rosenberg, when Frances was a freshman.

Frances Rodriguez was bright - an avid reader, priding herself on a straight-A report card. Luna said one of her younger sisters was put in a bilingual class simply because her last name was Rodriguez. The class moved at a slower pace than a regular classroom, which would have hindered her sister from learning at her fullest potential. Luna's parents went to the school to speak with the teacher, who eventually placed her sister in her rightful location.

In high school, Luna found an obstacle to her aspirations for perfect grades.

"My Spanish teacher had something against the little Hispanic kids. You sensed it," Luna said. "My goal was to make a straight-A report card, but I never did because I always made a B in Spanish."

The Spanish teacher told her she wouldn't grant her an A because she had "an advantage over the other kids" because she already knew Spanish.

When she graduated from Lamar Consolidated High School in 1955, she enrolled in Rosenberg Business College, where she earned her certificate. Luna then began working for the federal government with the Veterans Administration (now the Department of Veterans Affairs) in Houston.

On Aug. 6, 1961, she married Alfonso Luna, who worked at Dresser Industries coordinating intercompany sales. The couple had two children.

Luna did not forget some of the conditions of her youth in Rosenberg. One local drug store, at the time called Pickard & Huggins, forced Hispanics to eat their purchased food outside. At the Cole Theatre, Hispanics were to sit on the second floor of the building, and African Americans on the third. The city swimming pool, at Travis Park, didn't allow people of color to swim until a priest from a local church took the matter to City Council.

One particular instance stood out in Luna's memory. Macario Garcia, a Medal of Honor recipient, was denied service at the Oasis Cafe in Richmond, on Sept. 10, 1945, because he was Mexican. Garcia, wearing his Army uniform, objected and his friends came to his defense, arguing that he had sacrificed for his country. The dispute ended with Garcia's arrest on charges of aggravated assault. The incident made national headlines and galvanized Mexican Americans, who raised money for his defense. Garcia, a friend of Luna's father and later her colleague at the Veterans Administration, served as best man at her wedding.

Although Luna said her first voting experience was uneventful ("I just went in and voted"), that wasn't the case for many Mexican Americans living in Rosenberg in the '60s and '70s. In one instance in 1975, Mexican Americans were turned away at a school board election. This incident attracted the attention of Barbara Jordan, the area's congressional representative, who was also the first African American woman elected to Congress from Texas.

When the Southwest Voter Registration Education Project, an organization created to educate the Latino population about the election process, came to town, Luna became an active volunteer. Willie Velasquez, founder of the project, inspired Luna to take political power into her own hands. She said Velasquez traveled to Rosenberg from San Antonio to hold a voter registration drive and taught members of the community how to increase Hispanic involvement in politics.

"[Willie Velasquez] taught us to stick to the issues ... that are important to the people," Luna said. "You are here to help. You're not here to make a name for yourself or get recognition ... that's the biggest lesson I learned."

Velasquez trained Rosenberg locals to register voters in a professional manner. Luna heard later from a friend that when Velasquez and his trainers appeared in Rosenberg all at once, some people in town thought a Mexican revolution was underway.

"I guess we were seen at coffee or a restaurant or something," Luna said. "And I thought, 'How interesting that they think we are bringing people in from the outside to cause trouble.'

"No, we were bringing people in from the outside, from San Antonio, because that's where Willie Velasquez was, to educate and help, not to cause a riot," she said.

Luna said people found hope in some of the local political leaders. Lupe Uresti, a local woman, ran for City Council in 1976; she lost that election but won in 1978. Five terms later, in 1992, Uresti was elected as the town's first Hispanic mayor, which brought the community together. Luna participated in Uresti's candidacy for mayor by walking door to door, distributing leaflets and working a telephone bank.

"[Uresti's win] brought black, white, Hispanics, so many people out," Luna said. "That created an awakening that many people needed. If you work together, you can accomplish a lot."

Luna took Velasquez's teachings to heart and continued her volunteer work in politics. She joined the Spanish Language Advisory Board, created by the county's Elections Board Office to educate Spanish-speaking people in the Rosenberg area about the election process. The board was created in response to gerrymandering and at-large voting districts that suppressed minority votes.

As soon as Luna retired in 1994, she started working as an elections judge.

"I'm addicted to it almost," Luna said. "They teach you how to set up booths, just everything. It's a very enjoyable position."

Luna still lives in Rosenberg and works as an elections judge. She said staying politically conscious is crucial for understanding the ways of the world.

"If we're not careful, history repeats itself," Luna said.

Mrs. Luna was interviewed by Joan Vinson in Richmond, Texas, on March 23, 2014.