By Michelle Witters

San Antonio native Francisco Vega survived D-Day on Omaha Beach unscathed. That’s not to say he didn’t suffer acute pain later during the war, however.

When Sergeant Major Vega went to see the medic in Bad Kissingen, Germany, about a toothache, he was advised to live with the pain because there wasn’t any Novocain to aid in the surgical removal of his teeth. Vega recalls insisting on having them out, however, so the medic’s assistant tied Vega’s hands and feet to a folding seat, which Vega remembers looking like an electric chair. He recalls soldiers being summoned to help hold him down while the medic sliced open his gums.

It turned out Vega’s two lower wisdom teeth were impacted, so the medic forced them out with a tool Vega says looked like a screwdriver.

“[A]s he cut[,] there were a lot of ‘cracking’ sounds and the same sounds when he lifted the tooth. He then put [on my gums] quite a bit of the sulfa powder, gave me a bottle of scotch and suggested I start drinking it and to get in bed. I remember that while he was working in cutting and lifting out the teeth, under the trying conditions, he said, ‘My name is Sullivan and I am Jewish.’ He may have said this to lessen the stress under which he was working,” recalled Vega in writing after his interview.

Vega’s five-campaign career in the European Theatre began with the landing on Omaha Beach in Normandy on June 6, 1944.

“Many men didn’t make it to the beach. They would [fall] off the nets and be smashed between the ships” and the landing craft, he said.

“When I finally made it the beach, I was lying in the sand and the body of another soldier bumped alongside me and said, ‘ese [that] guy.’ I was surprised to hear Spanish and as I turned around to see this soldier next to me, I heard a dull, metal sound and there was a hole in his helmet. He was still and I never saw his face,” Vega wrote. “We referred to Omaha Beach as ‘Bloody Omaha’ … to me[,] it was as close to being in the killing floor of a slaughter house here in the states.”

Approximately 2,000 Americans died on Omaha Beach.

Rationing often made the war worse than it already was for the soldiers, as they ate very little and were often without basic medications.

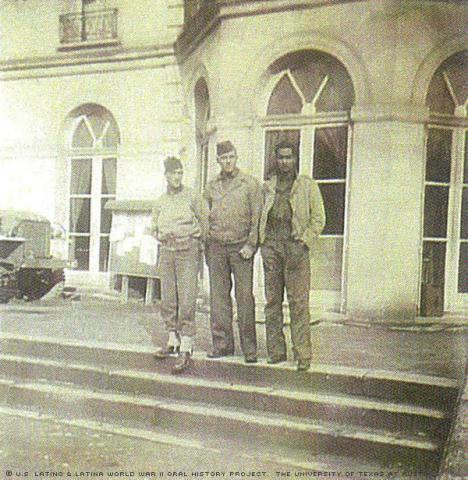

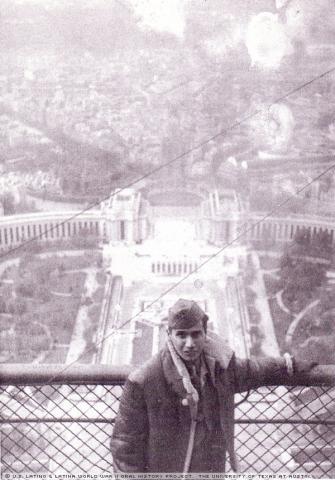

Vega was a private with the 392d Signal Company, later redesignated the 1709th Service Battalion, when he landed on Omaha Beach; 14 months later, he says he’d reached the rank of Sergeant Major. He fought his way from Omaha Beach to Cherbourg, France, his unit marching around Paris to Chantilly.

During the Battle of the Bulge, also known as the Battle of Ardennes, he drove a mechanics jeep into the German offensive, “to get one of our soldiers out who was alone and operating a mobile communications unit,” he wrote. “We drove two days and found him[,] but the firing was too close, so we attached magnesium bombs to the truck and the equipment that melted almost everything. We destroyed the mobile unit and got the soldier out and returned to Chantilly.”

When he was discharged Dec. 9, 1945, at the rank of Staff Sergeant, he was awarded several citations, including the American Defense Service Medal, American Campaign Medal, WWII Victory Medal and a French Presidential Military Decoration. The military also awarded Vega five Bronze Campaign Stars and several other honors for his wartime service.

*******

Four years earlier, a more innocent Vega was seeking out every military branch in San Antonio, Texas. Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor had taken place the day before, and with three years of ROTC experience, Vega wanted to serve his country.

“We are not taking Mexicans at this time,” was the response he recalls receiving each time.

Ten months later, however, the San Antonio Light ran an article wanting people with ROTC knowledge to help train troops.

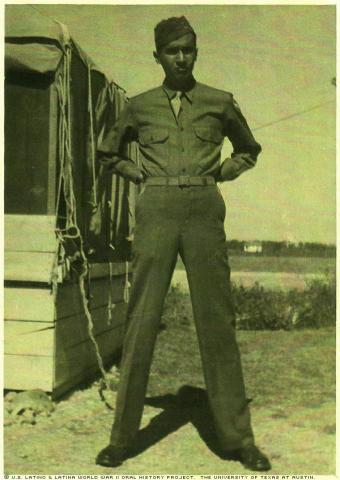

“On October 22, 1942, I was sworn into the service at Fort Sam Houston, Texas (infantry). I was then sent to Dodd Air Field (Army Air Corps) in Fort Sam Houston. I was transferred to the Air Corps at Kelly Air Base as a Drill Instructor (‘DI’),” Vega wrote.

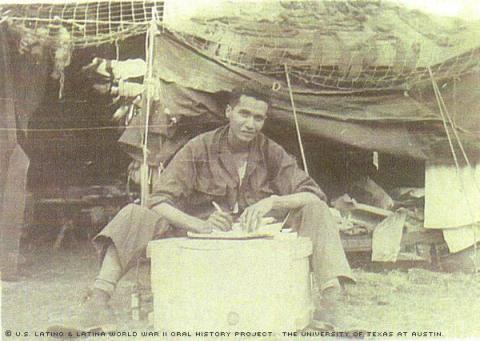

But marching wasn’t the only thing Vega was good at: He’d won two state typing championships during high school, and service administrators utilized Vega’s ability to type 117 words per minute.

While working weekends at the Kelly Field headquarters in San Antonio, Texas, Vega saw an order for the Judge Advocate General School, or JAG, in Baton Rouge, La. His request to attend was approved. After completing training in Baton Rouge in 1943, Private First Class Vega went on to Altus, Okla., where he says he received two promotions to the rank of Sergeant. He then went to engineering school at Oklahoma A & M, now Oklahoma State University at Stillwater, as part of the Army Specialized Training Program, but says he had to give up his promotions in order to qualify.

Next, he attended Bradley University in Peoria, Ill., where, in order to receive a four-year degree in 18 months, he was put into another engineering program courtesy of the Army Specialized Training Program. He believes he was the only Mexican American studying there at that time.

“There were 200 soldiers that started and within 60 days there were 100 left. In the next 30 days only 50 of us were left … chemistry was my downfall and I washed out.”

Vega was then shipped to Jefferson Barracks in Missouri, which he described as the “worst place I have ever been, before service and after service.”

“My rank was that of a Private and I was assigned to KP (Kitchen Police) to prepare the meals. We were awakened about 4:30 a.m.[,] taken to the kitchen and started peeling potatoes, mopping the floor, cleaning the tables, and anything else we were asked to do,” Vega wrote. “We cleaned everything after the breakfast meal, again after the noon meal, and another crew came in to clean after the dinner meal. We went back to the barracks again at 4:30 a.m. … every day.”

He didn’t stay there long, however, as he accidently burned down a dental clinic while on fire duty and was instructed to pack his bags.

Vega was sent off to Seymour Johnson Field in Goldsboro, N.C., where he worked for a couple of weeks before getting reassigned to Camp Miles Standish, near Taunton, Mass.

Vega was shipped to Liverpool, England, in the spring of 1944, where his typing skills opened the door to another opportunity.

“I was working on the teletype when I received the message that the 392nd Signal Company had arrived in England from North Africa. I requested and was granted the opportunity to transfer to this outfit,” he wrote.

After the war, Vega married Phyllis Lackland, who he met in 1943 while attending Bradley University. They raised three girls and are still married.

“After the war I used the GI Bill and went to college here, at Aquinas College and the University of Michigan. I graduated from Aquinas College in September, 1950. I managed five theaters here in Grand Rapids and taught Spanish in a local high school during my time in college,” Vega wrote. “I answered a box advertisement in October, 1950, to sell cemetery lots. By January 1951, I set a national sales record. … I progressed to half owner of a cemetery, [and] builder and owner of another cemetery…

Vega said he isn’t pro-military today, but thinks when “you live in a country with a representative government, you have to sometimes defend a philosophy. [You have to say], ‘That’s enough!’ and then fight for it,” he said.

“I am not a militarist,” he wrote, “but within borders are represented different philosophies, traditions, customs, beliefs, and when these are threatened and we want to keep them, we need to defend them.”

Mr. Vega was interviewed in Grand Rapids, Michigan, on July 2, 2007, by Juan Martinez.