By Sparkie Anderson

George Castruita has lived a full life. He served in the Pacific in World War II, traveled abroad, witnessed apartheid in South Africa, was chased down by "Paisanos" and had a young woman turn cold when she discovered he was Mexican American.

Castruita was also a firefighter for Los Angeles County for 18 years, before retiring in 1966. He has been married since 1948 to Priscilla Martinez, and is the father of three children and grandfather of eight.

Castruita was born in 1925 to Modesto and Amada Orozco Castruita, Mexican immigrants living in East Los Angeles. Like many other Mexican immigrants of the period, Castruita's parents left their homeland to flee the Mexican Revolution. Two of Castruita's uncles fought for Francisco "Pancho" Villa.

Castruita describes his childhood as a happy one. Modesto was a tailor who owned a tailor shop. The couple had three sons and one daughter. Castruita was the youngest of the four.

"We had the advantage of being raised in a community that was very multiracial," he said. "We mixed very well and I think it was very advantageous for us to be raised in that fashion."

Castruita says he grew up without feeling discrimination; at his schools, athletic teams were racially mixed. And he also didn't harbor prejudice against other groups.

Although Castruita reflects fondly on his racially diverse upbringing, he does have some memories of discrimination and violence that occurred in nearby downtown Los Angeles. Known as the "Zoot Suit Riots," Castruita recalls the incidents in which sailors and GI's beat up Latino youths.

He remembers the police refusing to help those who’d been beaten and hurt because they were Hispanic.

"The police got involved and they wouldn't do anything at the time," Castruita said.

"The so-called Mexican kids uptown ... they were abused something terrible because they were brown-skinned. In some instances they [the military] would take off their clothes and whip them and beat them up."

Castruita saw some irony in the beatings that occurred mere minutes away from the area in which he grew up.

"The sorry thing is the majority of those fellows who got beat up later went into the military to defend the rights and liberties of the country," he said. "Amen."

Castruita himself was going through basic training in San Diego when the riots were still occurring.

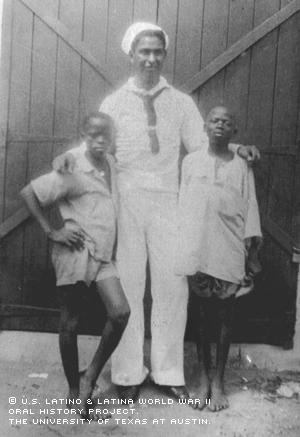

Not long after he graduated from Roosevelt High School in 1943, he followed in those men's footsteps when he joined the military that same year at age 18. He signed up for the Navy, serving two years and 10 months as a radio operator. His older brother, Oscar, served in the Army Air Force in the South Pacific for three years.

Castruita’s had a bumpy entrance into the military. During boot camp in San Diego, he was restricted to military grounds. Homesick and desperate to return to his well-known haven of East Los Angeles, young Castruita disobeyed the orders and hitchhiked home. When he was about four blocks from home, he saw, "what appeared to be a 1934 Ford two-door Sedan packed with Paisanos [young Latino males] and they looked at me in the sailor's uniform and said, 'There goes one,'" Castruita recalled

The Mexican men then chased Castruita all over the community in which he grew up, through back alleys, streets and other places he knew by heart. Although the Paisanos never caught him, the memory has stuck with Castruita all these years.

He also recalls meeting a young white woman in Dallas, Texas, who was friendly to him, thinking he was an Italian from New York. But when she found out he was Mexican American, she turned "ice cold," Castruita said.

"I never gave that much concern. I had always figured that I come from proud hard-working parents and if they do not care to know me, then they are losing out because I am a good guy," he said. "It is a funny thing, because she gave me the address of another girl that became my pen-pal."

Daily life in the military was routine: eight-hour shifts aboard an armed merchant vessel, on which he cleaned restrooms and guns, as well as did the work necessary for radio operation. He remembers a ship that was inclusive, with little mind given to racial differences.

He also remembers when his ship sailed into Cape Town, South Africa.

"I saw these people of color gathered at a railroad depot, and I said to myself, ‘This is not too bad," Castruita recalled. "But what I did not know was that they were leaving town. The people there had to leave town in their own country at sundown and would return at sunup."

When he understood the scene was apartheid, he says he felt disheartened.

When he needed comfort, Castruita, a devout Catholic, says he looked to his faith.

"When you are out at sea, especially if you are in a war zone, you are in God's hands. In some time and some date, you may have been there in harm’s way continuously, but it didn't affect me, nor did it affect too many of my comrades," he said.

The two ships Castruita sailed aboard, the S.S. Morgan Robertson and the S.S. Norma Clark, carried troops, Seabees (construction sailors), Marines, munitions and other cargo. He recalls one particular incident that brought the crew close to a battle at sea.

While sailing to a destination in the South Pacific, Castruita remembers a G.Q. (general quarters) alarm going off. The watch spotted a surfaced submarine a short distance behind the ship.

The submarine never engaged the ship in combat, however, and Castruita says that to this day, they never knew if it was a friendly or enemy sub. He believes if it was an enemy sub, they probably didn’t want to cope with the ship’s bigger guns.

After the war, Castruita was discharged in April of 1946. Despite some post-war nightmares, he says he had many great experiences during his time in the military. He recalls it as being, "a great time" of his youth and says he will continue to reflect fondly upon his years in the service.

"I hope that the telling of my story will be of benefit to future generations," Castruita said.

Mr. Castruita was interviewed in Los Angeles, California, on May 1, 2003, by Steven Rosales.