By Araceli Jaime and Jasmin Sun

G. Roland Vela was an 11-year-old delivering newspapers when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941.

Suddenly, everyone wanted to learn more about the bombing, and they swarmed Vela as he rode along his regular route.

“I sold all the papers I had[,] leaving me with none for my route customers,” he wrote later. “I was in serious trouble! But! Normally I sold 2 or 3 papers at 3 cents each; today people were paying a nickel -- I collected a pocketful of nickels.”

Raised in San Antonio, Vela said his only exposure to war before that day came from movies, newspapers and newsreels, which focused on wars overseas, including the Japanese attack on the Chinese city of Nanking and the bombing of London.

“[N]ow WWII was here. It was no longer in the background and far away … it was here, there, and everywhere. From one day to the next we went from being detached, semi-interested observers to being committed, dedicated and devoted participants in the war,” he recalled. “I thought I wanted to get into the war. Everybody I knew did.”

But Vela was too young to enlist, so he continued delivering papers and going to school until 1944, when he told his parents he wanted to join the Navy. At 15, he had joined the Texas State Guard but he wanted the real thing.

His parents signed release papers allowing Vela to enlist in the Navy at the age of 17, in June of 1945. By then, however, the war was over in Europe and appeared to be winding down in Japan.

“I remembered lamenting, ‘The war is going to end, and I won’t be able to get in!’ ” Vela said.

He got in, but instead of getting assigned to a ship, the Navy stationed him at the U.S. Naval Ammunition and Submarine Net Depot in Seal Beach, Calif., where he volunteered to work on the USS Makinsaw, a tug boat. After 13 months of peacetime service in the Navy, Seaman First Class Vela was discharged in July 1946, He was 18.

******Vela remembers growing up with an uncomplicated view of life.

The older of two children, he was born Sept. 18, 1927, in Eagle Pass, Texas. His parents, Marcial Vela Bermea and María de Guadalupe Múzquiz de la Garza Vela, taught him and his brother, Cesar, to value what they had, work for what they didn’t have and not to envy those who had more than they.

They lived in downtown San Antonio in a predominantly Mexican American neighborhood. Marcial worked as a clerk and a window trimmer for a clothing store, while Maria stayed home.

“She said she had her hands full with two boys, and I believe her,” said Vela with a laugh.

While Vela’s father and mother were fairly well read and fluent in Spanish, Vela and Cesar learned both Spanish and English. At home they spoke Spanish, but everywhere else they spoke English.

“If you spoke in Spanish, they would call you down on it,” recalled Vela of his time in elementary school.

Although discrimination toward Mexican Americans was common, Vela said he personally encountered it only rarely. “If you spoke Spanish, you would be punished,” he said.

Other than that, however, he recalled people getting along at the half-Latino, half-Anglo public schools he attended over the years. Even during his later years as a professor, and then as a dean of science and technology at the University of North Texas, he said he did not encounter obvious discrimination.

“Perhaps I was discriminated against,” wrote Vela. “I’m sure it was probably behind my back, but I could not see it [and] … no one ever told me about it,” he said.

A fear of prejudice, however, affected Vela and his wife when deciding whether to teach Spanish to their own children. “[It’s] a point that I’ve always been embarrassed about -- that we didn’t teach them to be bilingual and bi-cultural, and it would have been so easy for us to do it, but we didn’t,” he said. “We didn’t want them to start out with a handicap as we had.”

******After his honorable discharge from the Navy, Vela returned to San Antonio to finish his high school education, but he was quickly kicked out for his behavior.

“I got thrown out with a bunch of other guys who had also been in the service; we spent more time chasing the girls than learning. … We all smoked, we all cursed and we all told dirty stories,” he said. “We were generally a disturbing influence on the campus.”

Since he had already received his GED when he was in the Navy, Vela went to San Antonio Junior College and lived with his parents.

“[The director of admissions] told me, ‘We have to accept you … because you’re a returning veteran, and it’s the law,” he recalled. “But we don’t have to keep you, so we’re going to put you on scholastic probation. You’re probably going to be out by the end of the semester anyway.

...’ ”Vela was determined to prove the college wrong. “I wanted to study science,” he said. “I was always a heavy reader, and my favorite reading was science.”

After a year of all A’s and B’s, Vela asked the director of admissions how he could be removed from scholastic probation. The director reviewed Vela’s academic record and informed Vela that not only was he no longer on scholastic probation, he was now on the honor roll.

“After finding out that I was on the honor roll, I didn’t have to worry about getting kicked out of school anymore,” Vela said. “So I immediately went to chasing girls and drinking beer with everyone else instead of living like a monk.” He added later, “I also returned to the games of my life, chess and baseball.”

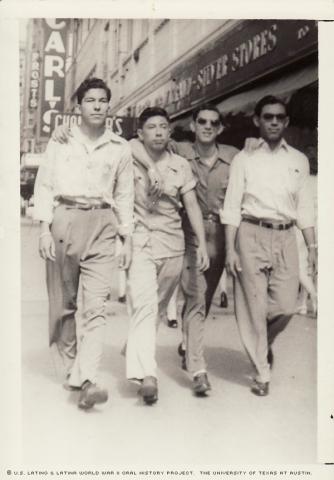

He didn’t get too carried away, however. Vela earned an associate’s degree and then transferred to the University of Texas at Austin in 1948.

“My parents gave me $70[,] which in that distant time was sufficient for transportation to Austin (bus $1.86), payment for a room at Little Campus Dormitory ($13 per month), and tuition and fees for 18 semester hours of junior level courses (approx. $35). This left me $20 for meals (breakfast, $0.25; lunch, $0.50; and supper with iced tea and dessert $0.69) and sundries to last until I received my first check from the G.I. Bill," Vela wrote.

After his junior year at the university, Vela said he had to choose a major so he could graduate. A close friend made the decision for him in an unexpected way. His friend and roommate asked Vela to take a course in bacteriology -- the study of bacteria and what they do -- so the two of them could share the cost of the textbook. Vela agreed, and then wound up liking the course so much he made bacteriology his major.

Vela described himself as a “self-motivated” man, a “go-getter.” During college, he held multiple jobs to support himself, like working as a caddy on a golf course, an auto mechanic and night orderly at Seton Hospital. He won a scholarship to get his bacteriology-major, chemistry-minor master’s degree in 1951.

“I earned my master’s in a year,” Vela said. “I worked from seven in the morning to midnight every day.”

He was about to begin his doctorate when he met a smart, attractive 17-year-old named Emma Lamar Codina Longoria, a nursing student at the Seton School of Nursing.

Because the nursing school did not allow their students to get married, Vela said, they had to wait until Longoria graduated to get married. Vela lived and worked in San Antonio as chemist in order to save some money.

They married in 1953. A year later, they had their first child, a son they named Gerard Roland. They would ultimately have three more children: Anna Maria, Yolanda Marta and Jaime Joel, born in 1956, 1958 and 1961, respectively.

In January of 1963, Vela received his doctorate in microbiology and biochemistry. After a short period of time in the civil service, he went on to teach graduate and undergraduate courses in microbiology at the University of North Texas in Denton, where he became a full professor in four years. In 1975, he was elected to the American Academy of Microbiology, and in 1985 he became Associate Dean of Science and Technology in the College of Arts and Sciences.

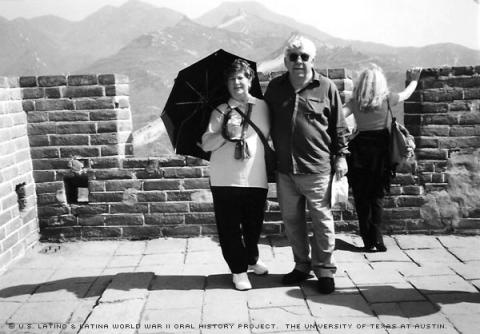

During his 35-year professorship at the University of North Texas, he directed the research of 20 doctoral and 44 master’s students. He also published 75 research papers, a textbook and an accompanying lab manual, all while serving on various committees for scientific institutions, as well as presenting and discussing his research with graduate students and faculties around the globe.

Vela also stayed busy outside of academia, getting elected to the Denton City Council and the Texas Municipal Power Agency Board of Directors.

“I’ve always thought that education was a means of getting whatever you want[ed],” Vela said. …“I’ve never thought that I was particularly smart or anything like that -- just a hard worker.”

Among other accolades over the years, Latino Magazine named Vela one of the top 100 Texas Latinos in the publication’s millennium issue.

“I was able to accomplish what I wanted,” said Vela, who retired in 2000 but continues to write and manage a personal business.

In 2003, Vela published “The Men Named Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna,” a biography of the Mexican leader. In 2006, he published another biography, “Bernardo de Galvez: Spanish Hero of the American Revolution.” He’s currently at work on a book charting the history of the Muzquiz family in Spain, Mexico and Texas.

Dr. Vela was interviewed in Austin, Texas, on Sept. 15, 2007, by Raquel C. Garza.