By Andrea Couch

Growing up in Santa Fe, N.M., in the '30s and '40s, Gilberto Delgado saw sign language for the first time: It was how one of his friends communicated with her deaf grandmother.

Later, that childhood exposure would lead him to take a role in education for the deaf, aiding him in earning his doctoral degree from Catholic University of America. Delgado also helped develop devices for the deaf, including closed-captioning for television and TTYs (text telephones) for phone communication.

"I was a part of a lot of those things," he said. "It was a very exciting time."

In his interview, Delgado took pains to steer attention from his own accomplishments. But his record speaks loudly:

• He has edited four books on deafness, including some that center on deaf Latinos.

• He edited one book on translating American Sign Language from English to Spanish.

• He helped some Latin American countries, including Costa Rica, Colombia, Mexico and Puerto Rico, develop their own sign languages.

• He was the first Hispanic superintendent in the country at a state school for the deaf.

• He was recruited and worked with the U.S. Department of Education in Washington, D.C. on close-captioning and telephone communications specially designed for the deaf.

All the while, Delgado was one of few Latinos in deaf education.

"We don't get a lot of Hispanics in the field. Why, I'm not sure," he said.

Born Sept. 3, 1928, in Santa Fe to Hilario Delgado and Ursula Apodaca Delgado -- a postmaster and a homemaker, respectively -- Delgado was only 14 when the United States entered World War II.

Delgado attended St. Michael's High School, an all-boys school, for 12 years, graduating in 1946. During the war, school went on as usual, but fewer students were enrolled because many of them left to fight. As part of the war effort, Delgado planted a Victory Garden and collected recyclables and rationed material.

"At school we had drives to collect metal and things the war effort needed," he said.

He also began working eight-hour shifts at the local post office while in high school.

"A lot of us did it because there was a shortage [of workers,]" Delgado said.

In his senior year, he visited a Navy recruiting office, had a physical and took an entrance exam. He scored well on the exam and the recruiter suggested Delgado go to the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, but he decided not to apply. He wanted to go to college instead of becoming a career military officer. Attending the Academy would commit Delgado to nine more years of duty.

"When you're 17, nine years seems like a century," Delgado said. "I just wanted to do my duty and get on with the career I was beginning with college."

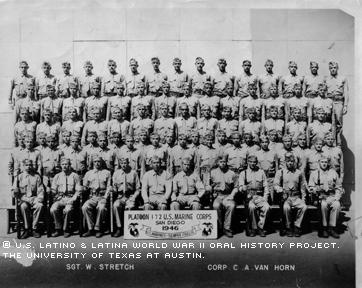

Delgado enlisted in the Marine Corps on August 27, 1946, a year after the war ended. His platoon at the 11-week training camp in San Diego included many Latinos from California's San Joaquin Valley and El Paso, Texas. The Hispanics frequently encountered prejudiced officers there. Drill sergeants often singled out Latino marines during training and called them derogatory names, such as "Pancho."

"They were convinced that we were all dumb, that we could never learn the drills and that we were going to be a failure as a platoon," Delgado said. "So we were extra careful and we never stepped out of line."

In written comments to the Project, Delgado added after his interview, "we took time to help each other and we were just as good as the rest."

Some of the Hispanic marines in the platoon -- some as young as 15 years old -- had trouble adapting to the pressure of basic training.

"They had a very tough time of it because they weren't physically or psychologically ready for it," Delgado said. "It took its toll on a lot of recruits because some weren't ready for getting yelled at or treated that way physically."

After completing basic training, Delgado's platoon was stationed in Okinawa, helping calm the unrest still troubling that area. The troop's assignment in the area was to help train local police to provide security for the islands. He spent more than 18 months in Saipan.

Delgado returned to Santa Fe in 1948 and signed up to remain in the reserves for three years. For his service during post-WWII, he was awarded the WWII Asian-Pacific Campaign Medal, the WWII Victory Medal and the Good Conduct Medal. He resumed his job at the post office and attended the College of Santa Fe; however, despite the familiarity of his surroundings, he had difficulty adjusting to life after the service.

"You don't quite fit into the routine that you left," Delgado said. "You're changed, more mature and you have a different perspective."

Delgado received his bachelor's from the College of Santa Fe, a master's degree from Gallaudet University in Washington, D.C., and his Ph.D. from Catholic University of America in 1969.

He and his family moved to Riverside, Calif., in 1954, where he taught at the California School for the Deaf for four years. He then transferred to a school in Berkley, Calif., where he served as principal for six years.

Delgado moved back to Santa Fe in 1988 and worked as superintendent of the New Mexico School for the Deaf for six years. He retired in 1994, but continues to serve on boards, including the Board of Trustees at the College of Santa Fe and the Board of Regents at the N.M. School for the Deaf.

Delgado married Cecilia Ortiz Delgado in 1949 and had six children. Right after they got married, the couple rented a small apartment, which had been used as part of a Japanese internment camp during the war. Because of the shortage of housing in Santa Fe, the camp was remodeled into affordable apartments for veterans.

"A lot of people in Santa Fe started out at the vet housing," Delgado said.

Cecilia died of cancer in 2001, and Delgado’s six children have moved away from New Mexico. His son, John, lives in California, where he works as an electronics engineer, and his five daughters; Jacqueline, Elizabeth, Elena, Carmen and Celeste; live in Maryland and are homemakers. Delgado has 21 grandchildren.

Mr. Delgado was interviewed in Santa Fé, New Mexico, on November 3, 2002, by Andres Romero.