By Jennifer Gallo

Gonzalo Garza's commitment to the Marines Corps began with the recruiting pamphlet. Of the five principles dubbed as "pillars" for that institution, Garza was particularly serious about using education as a guide after completing his service.

Born in New Braunfels, Texas, in 1927, Garza had only a ninth-grade education when he went to war, having dropped out to help support his family. He was one of 10 children born to his Mexican immigrant parents: An older brother and sister were born in Mexico, while the rest of the children, another five boys and two girls, were born in Texas.

During the 1930s, Garza’s parents, Carlos Garza and Victoria Gonzalez Garza, picked crops. He recalled how growers had but one question for applicants: “Cuantas manos tiene usted?” (How many hands do you have?) because the number of hands would [determine] the number of crops that you could pick," Garza explained.

Like many families during the Great Depression, the Garzas experienced dire times. Garza recalls how a relative came to the family's aid in 1933 during one particularly dark period.

"We were really almost starving because there was very little work for my father and food became scarce," he wrote after his interview. "My uncle, Martin Villareal, was better off, although he had a large family. Finding out our situation, he gave us half a wagon of corn. My mother made corn tortillas that we ate with some shortening and salt for a while."

Formal education for him began in 1937 in a one-room school in Schumansville, referred to as the "Mexican school," which catered to children of migrant workers. Because of limited interaction with Anglos, Garza began school "... not knowing one word of English."

Three years later, his family moved to Corpus Christi, Texas, where Garza attended Northside Junior High School until 1944, when he dropped out after ninth grade.

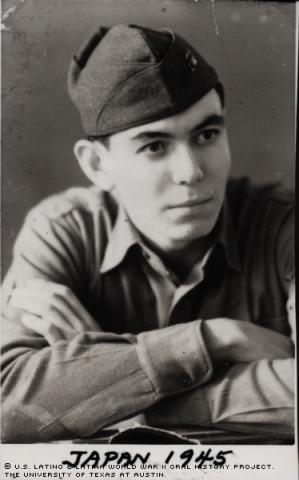

At 17, Garza joined the Marines and departed for basic training in San Diego, Calif. In May of 1944, he was assigned to Company E of the 7th Marine Regiment, 2d Marine Division, which landed on the islands of Saipan and Tinian. As they hit the shore, they were met with Japanese gunfire.

Garza was no stranger to the line of fire, including once when he was involved in a diversionary mission designed to draw fire from the Japanese. After 15 months in Saipan, his company was en route to Okinawa for a "fake landing." The disembarkation was a ruse designed to engage the Japanese into battle on one side of the island while the main body of troops hit full-tilt on the neglected side, which was left vulnerable.

While in Saipan, Garza attended a Japanese language school. The need for interpreters prompted the Marines to find men adept at learning other languages, taking Garza's bilingualism into account. He became quite conversant in Japanese during this time, but says he has since forgotten some 90 percent of what he learned.

On a return to the then-secured Saipan after Okinawa, Garza's mission was to help search for remaining Japanese soldiers.

"My job was to ... go out and search all the caves around the beaches because most of the Japanese soldiers that had remained and not surrendered, or had not been killed, were hiding in the caves of Saipan." Garza said.

Having reached the rank of Corporal, Garza was sent back to the United States in the waning days of the war, and immediately set out to resume his education.

"I promised myself, if I ever get back, I would graduate from high school, number one goal, and think about furthering my education and going on to college," he said.

He kept that pledge, earning his General Equivalency Diploma (GED) and enrolling at Del Mar Junior College in Corpus Christi. He thought of pursuing law, but realized it would take too much time. Instead, he decided to become a teacher. With the help of the GI Bill, he enrolled in the venerable San Antonio-based St. Mary's University in 1949, receiving $90 per month to subsidize his tuition and living expenses.

"The GI Bill has been, I would say, a savior for not only the Hispanic military persons, but anybody who served in the military had the right to claim that bill," Garza said.

By 1950, Garza was only two semesters short of earning his degree when his renewed studies were interrupted again, also by a war. Because he was in the reserves, he was called for duty during the Korean Conflict.

He landed in Korea on Jan. 10, 1951, on his 24th birthday. The cold climate proved to be fierce, and he succumbed to frostbite on his feet.

He was wounded in Korea, eventually receiving the Purple Heart. Having attained the rank of Platoon Sergeant, he was sent home in November of 1951, this time for good.

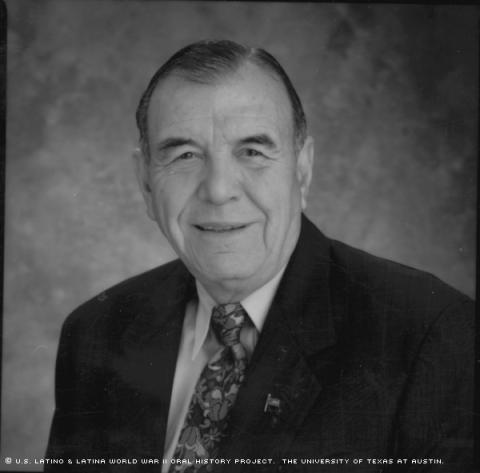

Garza stuck to his earlier promise, eventually earning degrees in Spanish and History. He’d later go on to receive a doctorate and become a sixth-grade teacher.

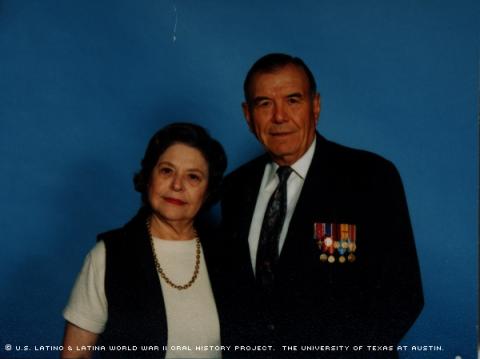

Aside from his memories, Garza has tangible reminders of his two tours of duty, having amassed several medals. He earned further recognition during the Korean War, for which he was awarded several medals, including the Purple Heart, Good Conduct Medal and Asiatic Pacific Medal. He also earned United Nations medals, multiple battle stars and Presidential Unit and Korean Unit citations.

Today, Garza lives in Georgetown, just north of the Texas capital of Austin, with his retired schoolteacher wife of 48 years, Dolores Scott Garza. The couple has five children: Charles, Louis, Patricia, Lawrence and David.

It should also be noted that Gonzalo Garza Independence High School in Austin is named for him.

Garza suggested a traditional Latino upbringing, with a healthy dose of deference to authority, enhanced Mexican American servicemen's contributions to the war effort.

"We did our duty with honor and glory, I would say. And we were in a way obedient to charges, to orders, to things that we were told, because that's the way we were taught," Garza said.

Mr. Garza was interviewed in Georgetown, Texas, on March 17, 2001, by Juan Campos.