By Miguel Gutierrez, Jr.

The first time Gregory Rios cast a vote was in the 1960 presidential elections, when he supported John F. Kennedy. It made an impression on him -- especially because of the poll tax, which people in some states were required to pay in order to be allowed to vote.

Rios had to weigh all of his expenses against how much he had to earn to pay for it. For someone whose livelihood was earned by picking cotton, the poll tax put a burdensome dent in his meager budget.

"If you picked a hundred pounds [of cotton]... you got $1.50 for it," he said. "The first time I voted, I had to pick a hundred pounds to buy a poll tax."

Rios was born in Rosenberg, a Texas town southwest of Houston, on Oct. 13, 1943. He was the fifth of 11 children of Antonio Rios and Albina Borjas Rios. After his father died in 1954, the family continued to work in the cotton fields and faced many economic and emotional hardships.

Rios was able to finish high school, but his political awareness would come in Vietnam, when arguments between Black and White soldiers would bring him a new perspective on his hometown, and the status of Mexican-Americans.

"At that time, there were 10 people in our family," said Rios. "When we weren't going to school, we were picking cotton to make ends meet."

Regardless of their poverty, Rios' mother was adamant about the need to vote to improve the status of Mexican-Americans and other U.S. Latinos. "I guess my mom saw what was happening to la Raza," he said.

Rios does not recall intimidation or violence at the polls. But Rios said he believed the poll tax was "just another way by the Anglos to keep minorities from voting." (Poll taxes in federal elections were banned by the U.S. Constitution's 24th Amendment in 1964, and the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1966 that poll taxes violated the 14th Amendment's equal protection clause.)

Discrimination took many forms. In schools, students were told "No Spanish Allowed." Like other Texan communities, Rosenberg was segregated and non-Whites where prohibited from entering certain sites.

"There were some places where we were discriminated and couldn't go in because of who we were," said Rios. "But we didn't know what discrimination was. My mother would just say, 'We can't go in there,' and we wouldn't, though, we never really knew why."

The West End was the part of Rosenberg where Blacks and Tejanos lived. The city was divided by a set of railroad tracks, which formed an unofficial border.

"All la Raza lived on the other side of the tracks with the Blacks," said Rios. "We were predominantly poor and we were in a little section by ourselves."

Despite both groups living in the West End, the minority communities were divided, and it wasn't common for them to interact.

"They stayed on their side, and we stayed on ours," he recalled. "That was the way it was."

School life, however, was different. From elementary to high school, Rios recalled that Tejanos attended school with Whites, while Blacks remained in the West End.

Rios reflected on the difficulties of Hispanics attending school with White students in that era and recalled the sense of superiority with which the White students would treat the Tejanos.

"When I was in dance class in P.E., we'd stop and switch partners, and this White girl would never touch our hands," said Rios. "That's the way it was: because we were Raza."

Rios lamented that racial hierarchies were not challenged at that time.

"In those days, we didn't question much," he said. "It wasn't our place to be asking questions. In those days, you'd mind your own business, and if it didn't apply to you, you wouldn't ask.

"I had never heard the word 'discrimination' before," he added. "I didn't even know it existed."

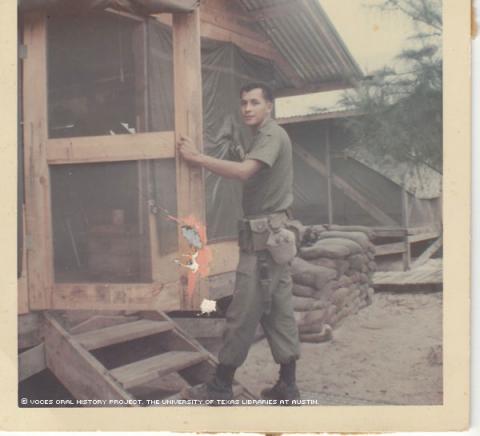

In 1965, like his father and brothers before him, Rios enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps. Before deploying to Vietnam, Rios was sent to boot camp.

While in basic training, Rios recalled heated racial discussions between Black and White soldiers. These conversations helped shape Rios' consciousness about the segregation and discrimination he faced in Rosenberg.

"I remember Black soldiers stating, 'Why should I be here helping these people be free, when I'm not free at home?'" said Rios. "I learned more in the Marine Corps about discrimination from watching the Blacks and Whites discuss."

Rios recalled boxing champion Muhammad Ali's opposition to the war -- most notably his refusal to be drafted -- and the influence this had on Black American soldiers who were serving in Vietnam. (Ali was jailed and stripped of his heavyweight titles for his 1967 refusal to be drafted. The government's denial of his petition for conscientious objection on religious grounds and for opposition to the war was overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1971.)

Rios also reflected on instances where minority soldiers questioned their role in a war in which the U.S. forces were said to be fighting oppression, while many of them felt terrorized and oppressed back home in the United States.

Rios left for Vietnam in 1966, and returned to the United States a year later with a new awareness of the discrimination he had faced in Rosenberg.

"There are five members in my family that are veterans, my dad and four of us [siblings], and the four are still alive," he said. "I ask myself, 'Why do I defend this country with what they did to us?' "

The war also had a toll on Rios' health. Through the years, he was afflicted with skin and liver problems, prostate cancer and heart damage, which he attributed to exposure to Agent Orange, a defoliant used during the war. He also suffered from hearing loss from the loud detonations of battle armaments

Despite his skepticism about the war, when asked if he would still serve in Vietnam, knowing what he does now, Rios acknowledged that he would.

After the war, Rios resumed his life in Rosenberg. Less than a year after his return, he married Ida Lopez Rios, with whom he had two sons. Through the years, he was involved in a number of veterans' organizations, such as the Veterans of Foreign Wars, and remained politically active.

At the time of the interview, Rios was a regular guest on Wolf Pak Radio, an online Houston-based station featuring Tejano and conjunto music, which Tejano soldiers can access while abroad. On a talk show, Rios discussed challenges that veterans may face when returning home, and how to address them.

Rios' belief in the power of the vote, a value he first learned from his mother, has remained unchanged.

"Now, I get all of my family to vote. I tell my grandson 'You need to go register to vote,' " he said. "You have to get involved; you have to know what's going on around you."

Mr. Rios was interviewed in Richmond, Texas, on March 22, 2014, by Miguel Gutierrez, Jr.