By Melanie Jarrett

By the time World War II ended, Guadalupe Garza had traveled hostile roads through French Morocco, Spanish Morocco, Algiers, Tunisia, Sicily, Italy, Gibraltar, Scotland, England, France, Belgium, Luxemburg, Germany and Austria.

In all, he experienced 480 days of combat.

Now 82, Garza grew up in the midst of the Great Depression, the oldest son of a ranch hand and his wife. He was drafted into the U.S. Army one month after Pearl Harbor was attacked. In almost four years of service in WWII, he participated in nearly every major battle in the European Theater before being discharged in 1945.

His rugged upbringing on the Texas-Mexico border helped him learn to deal with the hardships and challenges of the war. It also made him thankful for what he had, he says.

"During the Depression, we had a cow and some chickens, so we always had food to eat," Garza said. "We were lucky."

He had the opportunity to attend school for seven years in his hometown of Eagle Pass, Texas, about 140 miles southwest of San Antonio, before leaving to enroll in the Civilian Conservation Corps in October of 1937, he says, adding that he started school late and was 18 when he entered the seventh grade.

"I loved school, and I always tried hard to make the best grades," he said. "That way even if I was poorer than them, I could at least be smarter."

Garza was the oldest of four brothers and a sister and says he received more schooling than most of his siblings. He remembers encountering frequent prejudice.

"Every morning I had to walk by the same gringo's ranch," he said. "And every morning he would ride out on his horse and try to lasso me with his rope on my way to school."

It wouldn’t be the last time he’d experience discrimination.

After being drafted in January of 1942, Garza was sent to Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio. It was his impression that "only the Mexicans were going to war. There were no gringos at our camp at all."

At Fort Sam Houston he was given the opportunity to choose his assignment, so he says he followed the advice of a cousin and picked an artillery unit.

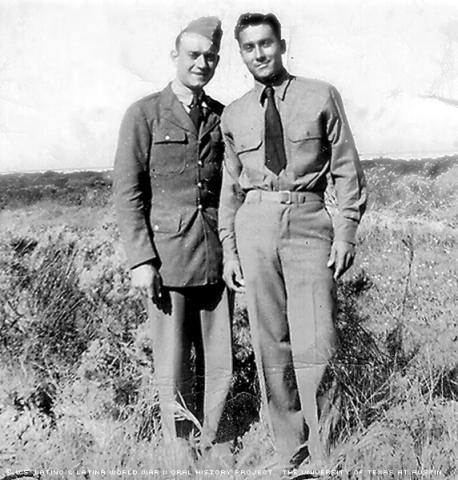

"I had this cousin that was in there with me, and he told me and about 10 other Latinos to join the artillery," Garza said. "So we all did, but once we got overseas I never saw them again. I was the only Latino within 10 miles of my unit."

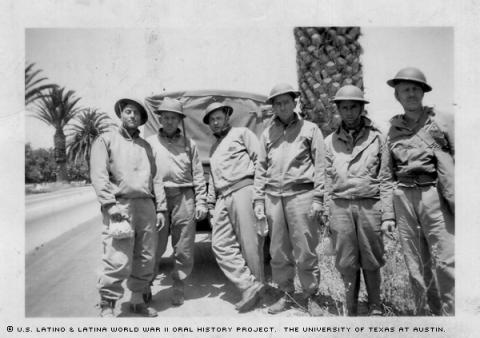

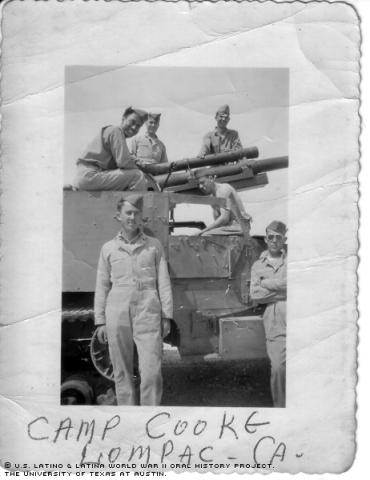

Garza was a gunner in Battery B of the 58th Field Artillery Battalion. His unit trained for about four months before being sent to Tunisia, Africa. He remembers there being much uncertainty about where his unit was going.

"We weren't really sure what our assignment was going to be," he said. "There was a time when we thought the Japanese were going to invade Los Angeles."

He saw his first combat in late 1942, when the Germans began bombing his unit in Casablanca, Morocco. The raid started about 9 p.m. on New Year's Eve and created what he called "the most beautiful fireworks I had ever seen."

"We shot 12 planes down, but then one flew so low over us that we saw the shadow of the plane on the ground," he said. "So 10 of us ran to this foxhole full of water and jumped in. I didn't think I was going to last very long, but God saved us."

His unit also took part in the invasion of Sicily that began on July 10, 1943; the fighting was tough, Garza says. German troops surrounded them in Brolo when they landed behind enemy lines on August 14, 1943. That day, the unit lost their four 105 Howitzers and many men.

Garza recalls swimming for his life at Cape Orlando.

"Another guy, L.C. Smith, and I headed for the beach and hid in the water, and when we looked back we could see the Germans gunning down the men as they reached the top of the hill," Garza said. "We swam around Cape Orlando all night and then hid for seven days without water and eating only grapes before we finally reached our troops in the rear echelon."

Garza also participated in the largest Allied troop assault of the war when his unit stormed Omaha Beach in Normandy on D-Day in 1944.

The fighting on Omaha Beach was fierce, Garza says. He and fellow soldiers feared for their lives as they dodged enemy gunfire. He recalls that many of his comrades tried to scale a tall embankment, but the effort was disastrous.

"We got grapes in Sicily, but only bullets in Normandy," he recalled.

After narrowly escaping death in Normandy, Garza next saw action at the Battle of the Bulge in Bastogne, Belgium, a hamlet in the southeast of Belgium that U.S. forces took from German control.

In the preface of “Nuts: The Battle of the Bulge,” authors Donald M. Goldstein, Katherine V. Dillon and J. Michael Wenger, describe the battle as “a patchwork quilt – a multitude of small engagements played out in or near small towns, most of no military significance.” Despite this fact, the U.S. suffered approximately 81,000 casualties, including 19,000 killed; The British suffered around 1,400 casualties, including approximately 200 killed. Germany lost an estimated total of 100,000 -- dead, wounded and captured. Image after image in Nuts is dominated by snow and rubble, complete destruction.

Garza says he was left 20 miles behind enemy lines, where he dug a hole in the snow-covered ground and buried his wallet and pictures in case he was captured. After traveling 20 miles through the snow, he was found on Jan. 2, 1945, and sent to England to be treated for frostbite on his feet.

Then, while on a road in Belgium, Garza became a victim of battle.

"We were out on the road and mortar shells were falling all around us," he said. "A shell exploded right by me, and the shrapnel from it hit me on the eyebrow, leaving a big dent in my helmet and a huge gash on my head. I was lucky it hit me in my helmet. Any lower and I would have been dead."

He spotted a hole in the ground where medics were tending the wounded. They dressed his wound and sent him right back into battle.

After the Battle of the Bulge, Garza's unit moved into Austria in May of 1944. That's where he learned that Germany had surrendered.

Garza returned home as a decorated war hero, earning the Purple Heart and a Presidential Citation, among other honors. But despite his hero status, he discovered on his arrival back in Eagle Pass that life hadn’t changed as much as he’d expected, or as much as he’d wanted.

"There was still discrimination against the Mexicans," he said. "I had a friend that had served in the military who was kicked out of a hotel for being colored. But he went and became a lawyer and came back and shut the place down. He got the last laugh, I guess."

Garza began working at a gas station that his cousin owned. In 1947, he married Maria Mauricio, with whom he has two children, Jose and Maria.

He retired from El Camino Hospital in Mountain View, Calif., where he was a stationary engineer for 22 years. He later invested in California and Texas real estate and moved to Eagle Pass, Texas.

"My children had a lot better life than me," he said. "I always told them to get their education first so they could get a better job later on."

Both of Garza's children have done just that. Jose and Maria both graduated from high school and Jose completed a year of college before successfully entering the workforce.

"I wanted them to have better opportunities than I did," Garza said.

When he looks back on his World War II experience, Garza says he’s fortunate he cheated death over and over during the war.

"I was lucky," he said. "All I wanted to do was get my discharge and go home."

Mr. Garza was interviewed in Houston, Texas, on September 20, 2002, by Domingo Marquez.