By Lindsey Craun

When 18-year-old Hector Sanchez learned he had been drafted into the U.S. Army to fight in Vietnam just three months after his high school graduation, he knew that he had to face the reality, look forward to the challenge and remain optimistic.

“I believed out of the goodness of my heart, to me, this is the best country you can live in,” Sanchez recalled. “And if you want to live in this country, you've got to fight for your country."

Throughout his experience as an infantry soldier in Vietnam, Sanchez gained lasting friendships, life-changing memories and, above all, a greater sense of pride for his country.

Sanchez grew up in Sonora, Texas, a small town 172 miles northwest of San Antonio. His father, Alfredo Flores Sanchez, worked shearing sheep and in construction. His mother, Marcelina Noriega Sanchez, tended the house and took care of the couple’s two children. Sometimes Sanchez skipped school to work and help out his family. Though times were rough, working alongside his family and friends made them all closer.

"Our parents … showed us how to survive. They made money the honest way, and they sacrificed for it,” Sanchez said. “There wasn't much work going on around Sonora, but we survived. We made it."

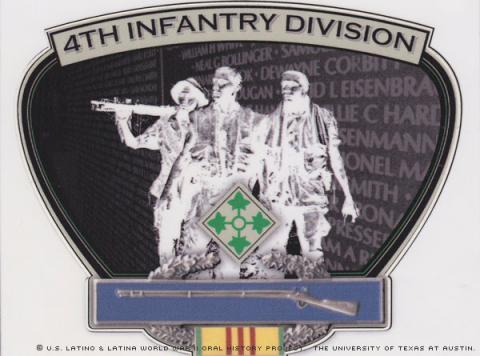

That same drive for survival would serve him well in the military. After basic and infantry training, Sanchez was sent to Vietnam in 1969, serving until 1970. He was assigned to the 3rd Platoon, Co. B, 3rd Battalion, 8th Infantry. The first few months were frightening, but Sanchez remembered that he quickly grew accustomed to the conditions.

One of his friends, Juan Anzaldua from Chicago, wrote a letter in 2009 in which he noted that the two had “humped” many hills throughout the jungle, and they had suffered a great deal. Anzaldua asked the reader to help Sanchez.

Sanchez recalled a fellow infantryman who couldn’t handle the trauma of war. The soldier escaped into the jungle, never to return.

"I was scared. Anybody is scared when you see bullets flying over your head,” Sanchez said. “A lot of guys can't take it. You get used to seeing people lying on the ground. All you have to do is go forward and survive, that's all."

He recalled spending 20 to 30 days at a time out in the field, sometimes eating only once a week. Some members of his platoon helped each other, Sanchez remembered. Because of that support, he was able to focus on his work and manage the tremendous pressure he and other soldiers endured.

He attributed his survival to a buddy system that he developed with a friend he grew especially close to. Sanchez remembers instances where soldiers fired at other soldiers they didn’t like. He and his friend’s buddy system helped protect them against friendly fire and other dangers.

Sanchez recalled a time when his platoon discovered a cave filled with a variety of weapons. The enemy soon ambushed his group and pinned them down for two to three days until help arrived.

"I can't really explain it to you, but anger makes you fight,” Sanchez recalled. If you want to survive, you can make it,” he said. “I don't care where it is; you can make it if you do the right things.”

Sanchez was never physically wounded in battle, but he felt emotionally wounded. Sanchez described a time when he watched his friend, Joseph, take a bullet from the enemy just 20 feet in front of him. Sanchez, who weighed 140 pounds, managed to drag the 220-pound Joseph nearly 70 feet to safety, he said. But Joseph, his best friends, still died.

After serving his required year, Sanchez returned to the U.S and was honorably discharged at the rank of private first class in 1975.Among the medals he received were a Bronze Star, a Cambodia Medal, two medals for good conduct, and CAB for combat.

But the mood in the country when he returned was very anti-veteran, Sanchez remembered. He saw on television as anti-war protesters threw rocks at military men arriving Washington D.C. and called them “baby-killers.” Many people ignored Vietnam veterans altogether.

American citizens may have shown little appreciation, but Sanchez held the U.S. government in high regard. In his eyes, the government took good care of him and his family over the years.

For the next 30 years, Sanchez worked in the oil industry, but then the company decided to move to Mexico. He worked in construction for Transfer Atlas in Sonora, until his retirement in 2001.

Sanchez married Carmen Galindo on Nov. 21, 1973. The couple had two sons and one daughter.

Sanchez recalled that retirement didn’t bring him peace of mind. He struggled with post-traumatic stress disorder. He said that whenever he saw anyone get hurt, or when he watched war movies, he became emotional.

His squad leader, Donald Fields, wrote a letter in support of Sanchez, noting that, “On 4 October 1969 we received rifle fire from enemy forces. PFC Muench was shot approximately 20 feet from Private Sanchez during the initial contact. … This is an extremely stressful combat event, especially for a young infantryman witnessing his best friend and squad member as his first friendly that was killed in combat.

“I met Hector at a reunion of our Battalion in June of this year,” the letter continued. “This was the first time that we had seen each other in almost 40 years. After talking with and commiserating with Hector, I strongly advised him to seek help after he told me of his thoughts and feelings, and witnessing his obvious distress,” Fields wrote.

Sanchez said the Department of Veterans Affairs helped him through his struggles, for which he is very grateful. Sanchez said he wanted to help other veterans dealing with PTSD. He planned to open an assistance center in Sonora.

"Now that I'm disabled, they help me at the Department of Veterans Affairs,” he said. “They furnish anything I want, they take care of me, and I believe somewhere else they wouldn't do that.

"I know a lot of veterans that are hurting right now that can't afford to travel to San Antonio [to receive medical care]. And by doing that they can still live here and get free medication."

Mr. Sanchez was interviewed on Aug. 1, 2010 in El Dorado, Texas by Liliana Rodriguez.