By Sherri Fauver

For a generation that experienced both the Great Depression and the trials of World War II, hardship and sacrifice was a fact of life.

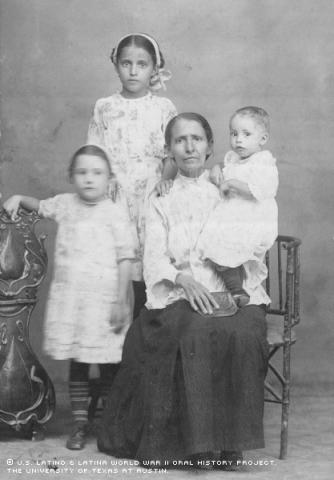

If you add to that, the experience of being a Latino and a woman at a time when neither group was well regarded, you could have the making of a melodrama. Unless, of course, you are talking to Henrietta Lopez Rivas.

Like most members of her generation, Rivas recounts the hardships of her life with relative nonchalance. In many ways, she epitomizes the dictum of her generation: You didn't think about how hard it was. You just did what you had to do to survive.

Born on Feb. 14, 1924, on the East Side of San Antonio, Texas, she grew up during the Great Depression, but she doesn't dwell on the negatives.

"We were very poor, but very happy", she said, a fact she attributes to her mother. "I remember a very caring mother, extremely caring mother. She taught us that pride is, "Es todo." Is everything.

Her mother also took pride in her children's education. By the time she started school, Rivas knew her multiplication tables and was able to read Spanish. It wasn’t enough, however, to help her compete in an educational system unsympathetic to the needs of Spanish-speaking students: Rivas failed the first grade because she didn’t know English.

The schools in San Antonio weren’t officially segregated, but she remembers that all "Mexicanos" sat in the back of the classroom. "If we didn't know the answer to something, we would raise our hands because we were never called on," she said with a wry laugh. "But to us, you know, 'So what?' You took it like that. That was how you survived."

She stayed in school only through the ninth grade. The Depression was beginning to drain the Texas economy, and the poverty-ridden Latino community was especially hard hit. When her stepfather lost his job of 12 years, the family found itself in danger of losing its southside home.

They owed only $500, but her mother refused to stay if they couldn’t find work to support themselves. So, when she was only 15, Rivas headed north with her family to earn a living as migrant farm workers. She spent the next several years in the tomato and sugar beet fields of Indiana and Michigan, where she remembers working from dawn until dusk for little pay. "It was slave labor," she said, "Don't forget it."

Upon returning to San Antonio, she took on jobs cleaning houses and barnyards for only $1.50 a week. However, it was 1942 and the war was beginning to rejuvenate the U.S. economy. Like many other women during this time, she found herself with employment opportunities that previously had been closed to her.

What had once been a liability in school now became an asset: The Civil Defense Department was in need of Spanish-speaking interpreters. Rivas went from making $1.50 a week to $90 a month. Despite its many hardships, the war had given her something she hadn’t experienced before: a sense of equality. She was valuable because she was able to offer services that "Anglos" could not. She was valuable because of her heritage.

"It made me feel equal, more intelligent, because what I did, very few Anglos could do," Rivas said.

This was not the only major change in her life. It was at this time that she met the man who, in 1945, was to become her husband. Ramon Martí¬n Rivas was on leave from the Aleutian Islands and was staying with relatives who lived across the street from her family, which was traditional and very strict about dating practices. She remembers opening the door to find Ramon standing on the front steps. Her only words to him were, "Get the heck out of here. I can't see you." But he was persistent and was soon granted the opportunity to court the 18-year-old girl. The courtship was to be short lived, however, as Ramon returned overseas.

Meanwhile, she continued to take advantage of the many opportunities created by the labor shortage. She had heard of better jobs being offered by the Civil Service at Duncan, now Kelly Air Force Base. And after passing a barrage of tests, she was offered employment repairing all airplane instruments. It was to become another affirmation of her exceptional ability.

She loved the work and took it seriously. The dedication paid off and she was soon promoted to assistant supervisor of her department. She is quick to note, however, that she was given nothing.

"It was because of my ability," she said.

The war had given her belief in herself. After the conflict, she used this strength to support her own family. The young soldier who’d courted her years ago returned and they married on Feb. 11, 1945. Soon after, she gave birth to a son, the first of seven children and the only boy.

Her experiences during the war gave her a strong sense of independence and self-reliance, the value of which she tried to instill in her children. She hopes to see more of these values within the larger Latino community.

When asked if she thinks circumstances are better for Mexican Americans now, she responded, "In a way they are. In a way they're not. They (Mexican Americans) are too dependent on the government to give them sustenance," she said. "I think all of us should work for what we have."

Mrs. Rivas was interviewed in San Antonio, Texas, on June 12, 1999, by Veronica Flores.