By Whitney Sterling

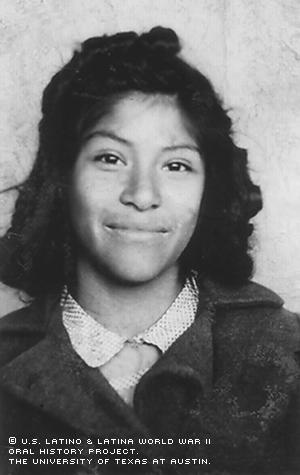

On the morning of Dec. 7, 1941, the entire Buitron family, including all nine children, was sitting in church when the pastor shocked the congregation by announcing the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor. For Herlinda Estrada, this was more confusing than informative.

The 11-year-old wondered what it all meant. Her only knowledge of American wars had come from reading history books. Now, she, like a whole nation, was forced to deal with a world war that would last four difficult years.

"I didn't really know what to think because I didn't really know what war was," Estrada said. "I knew it wasn't good because when Japan attacked at Pearl Harbor, we learned that one of my mom's friend's son[s] had been killed."

Estrada's family would be pulled into the war effort both abroad and at home. Her brother, Adan Buitron, saw combat in New Guinea and the Philippines and served in Australia while in the Army.

Her future husband, Johnnie Estrada, also served in the Army, working as an engineer in Europe.

Even though Estrada was young during the war years, she still found ways to support the war effort and help her country. For example, she babysat for the officers' families at Camp Swift, a temporary Army camp near her hometown of Bastrop, Texas.

"Mama said it was OK as long as I returned the same day," Estrada said.

Other family members participated in the war effort by collecting scrap metal and buying savings stamps, which were used to buy war bonds.

"Everyone pitched in," she said.

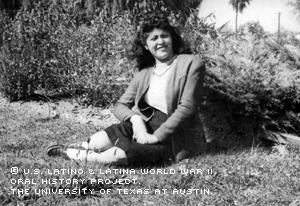

Born in 1930 in Bastrop County, Texas, Estrada grew up as one of nine children of a coal miner and homemaker. She recalls spending most of her childhood in the small mining communities located throughout the county, and describes her childhood in them as simple but happy.

"We didn't realize we were poor or anything because everyone was in the same condition. We had a good life," she said.

Estrada remembers attending elementary school in a one-room schoolhouse and later being segregated from Anglo schoolchildren at a school entirely comprised of Mexican Americans. She says Bastrop only had one high school, and Mexican Americans were forced to attend high schools in nearby Taylor and Hutto.

It wasn’t until she entered the ninth grade that segregation finally ended at Bastrop High, says Estrada, who credits one particular teacher for desegregating the local school system. Estrada recalls the teacher, a white male married to a Mexican American teacher, standing up for her and other Latino students and pressing the local superintendent on the issue.

"He said to the superintendent, 'The kids in my class are going to stay at your school whether you like it or not, because their parents are taxpayers,'" Estrada said.

"You see, it's the parents [who wanted segregation], not the kids," she said. "There was a togetherness between the kids in the white community and the kids in the Hispanic community. Kids don't see the differences."

Schools weren’t the only parts of the community that were segregated: According to Estrada, local restaurants forced minorities to enter their establishments through the back door, where they could order their food; storefront signs saying minorities couldn’t sit and eat in the restaurants notified them of the discriminatory policy, she says.

"A lot of times I played dumb," Estrada said. "I would say to myself, 'Well, I don't know how to read your sign,' so I'd go through the front door. And I got waited on for the simple reason that I knew how to speak English."

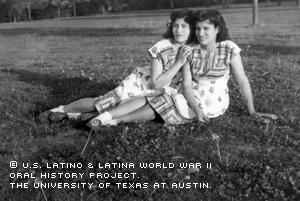

Estrada's command of English was due to her older sister, Benita, who’d taught her English and math before starting public school. Estrada’s language and math skills would become beneficial to her later in life: During the summers, she and her family picked cotton. Because she was well versed in English and math, she became the keeper of the family books, keeping track of hours worked, number of pounds of cotton picked and monies owed to family members. She says they were paid $1 for every 100 pounds of cotton, and that the field boss knew he couldn’t cheat her because she spoke English well and kept accurate records every week.

Estrada recalled that life changed in many ways as a result of the war. Certain goods such as gas, sugar and shoes were rationed. She says they simply did without when those items were unavailable.

During the war, her father worked for a local dairy and, later, for the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad. He lost his railroad job at the end of the war. When her brother, Adan, returned from the war in 1946 and couldn't find a job, the family decided to move to Michigan.

They ended up moving to Saginaw after Estrada's first year of high school. Once in Michigan, she didn’t return to school, as she was forced to work in the fields to help her family’s situation. The women worked in the beet and bean fields; the men, at a metal foundry, Estrada recalls.

The family didn’t initially have a place to live. She recalls her dad going door-to-door, asking to rent a room where he and the rest of the family could live. Estrada recalls her father finally arriving at the home of her future husband, where her father rented a one-room apartment.

"One day my future husband came and asked me if I would help him get all of his pictures and scrapbooks together from the war, and I said yes," Estrada said. "And that is how we met."

They were married on Nov. 1, 1947, and eventually had five children. Once married, Estrada’s husband took a job at General Motors, while she stayed home raising the children."Our goals were to have our children go to school all the way through high school," Estrada said. "All five graduated from high school and three went to college."

Once she finished raising her children, she worked at a bakery for 20 years. She’s now retired and still lives in Saginaw.

After retiring from the bakery, Estrada says she still had one more goal to complete -- attaining her high school diploma.

Approximately 35 years after she was supposed to graduate, Estrada returned to school, finishing in 1985.

Mrs. Estrada was interviewed in Saginaw, Michigan, on October 19, 2002, by Gloria Monita.