By Karin Brulliard

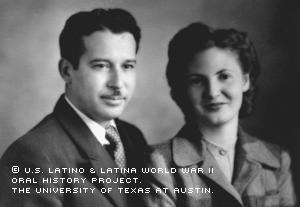

When Imogene "Jean" Davis first laid eyes on Alfred Avalos in September of 1942, she didn’t notice he was more than a decade her senior, and that his skin was several shades darker than hers. She saw only that he was handsome.

It was her first day as a clerk at Eckmark photography studios at Camp Walters Army Base in Mineral Wells, Texas. Alfred, who went by Pat because he was born on St. Patrick's Day, was a photographer there.

He was taken himself with the 22-year-old woman.

"He says, 'Well, you don't know the town very well. We'd better go on a date,'" she recalled. "I found out later that when he saw me, he told one of the other workers, 'I'm going to marry her, so help me.'"

Three weeks after their first date at a barbecue restaurant, the two slipped across the alley behind the studio to the office of the Justice of the Peace. There, they said their vows, and Alfred slipped a three-diamond ring on Mrs. Avalos’ left hand.

That day marked the beginning of a loving 55-year marriage. It also introduced Avalos, an Anglo, to firsthand experiences of discrimination against Latinos.

Avalos spent most of her childhood in the Northern Texas town of Crystal Falls, a close-knit rural community of 100 where townsfolk gathered for summer fish fries on the banks of the Clear Fork of the Brazos River, and held dances in an abandoned dance hall.

Avalos and her four younger siblings led the lives of country kids: They hunted skunks and possums with .22 rifles, took ice-cold showers in an outdoor washroom and tended to the family's vegetable garden, pigs and cows. But they balanced lots of work with lots of play, she said.

"In the summers, we'd swim every day," Avalos said. "We'd swim until it got so cold we couldn't, and when it got warm, we'd be in the river."

As the section foreman between Brackenridge and Throckmorton for the Cisco and Northeastern Railway, her father, Flimon Davis, repaired tracks and roadbeds. His steady job kept the Davis family afloat during the Depression years.

Railroad laborers -- most of them Mexican -- lived with their families in barracks next to the Davises' two-bedroom home. Avalos and the other children in town played and attended school with the Mexican and Mexican American children -- learning some Spanish, especially curse words.

"We were just all kids," Avalos said. "The only thing that was different was that they could talk another language that we didn't know."

After graduating in 1938 from Breckenridge High School, Avalos worked for the chamber of commerce in Mineral Wells, helping find housing for people working at Camp Walters. A year later, she moved to Abilene to be a stenographer for a music company. Dressing for church one morning, she heard on the radio that Japan had bombed Pearl Harbor.

Suddenly, "everything changed," she said.

Avalos’ two younger brothers, Wayne and Lester, went off to war. After her job in Abilene ended, Avalos moved to Mineral Wells to work at the photo studio.

"That's when I found out there was a difference [in the way many people treated Latinos and Anglos]," Avalos said.

Landlords welcomed her when she looked at apartments by herself. But when she returned with Alfred, the apartment was mysteriously unavailable. The couple saw three places before they were able to rent one, she says.

"He was Hispanic and I wasn't, so I could get an apartment and he couldn't," Avalos said. "It was such a shock to me ... I wasn't taught that there was two different kinds."

During the next few months, Avalos ignored the stares and raised eyebrows of people who disapproved of mixed couples. She shrugged off questions about why she had married a Latino. The opinions of strangers were unimportant, she says. Her family adored her husband, and his family treated her "like a queen."

Just two months after their marriage, Alfred was drafted into the Army and soon left for Europe. Avalos, pregnant with their first child, went to stay with her parents, who’d moved to Monahans, in West Texas. It was a tense time, rushing to the mailbox each day and listening to the radio with crossed fingers.

"You live on a continual 'What's going to happen?' You can't relax," Avalos said. "Every time the phone would ring, I would jump sky-high."

Alfred, a staff sergeant of the 112th Infantry Regiment, 28th Infantry Division, often sent love letters and photos of himself in front of French cottages and on Belgian bridges. The photos and letters offered Avalos happiness and relief.

When the war ended, Alfred stayed on as a war-crimes photographer; many of his photos showed concentration camps. Not until he returned home did Avalos learn Alfred had been wounded during the December of 1944 Battle of the Bulge and awarded the Purple Heart.

"He kept saying, 'I'll be all right. Don't worry,'" she said. "And I just had faith he would."

Alfred was discharged in December of 1945, and returned to his wife and 17-month-old daughter, Jeannie. When Avalos’ brothers also returned from the war unscathed, she felt tremendous relief.

The family later moved to San Antonio, where they lived near Alfred's sister and her husband. Avalos felt comfortable with her Mexican American family and quickly learned to love Mexican food.

In San Antonio, Alfred worked as an aircraft painter at Kelly Air Force Base; Avalos stayed home to raise Jeannie and their two other children, Michael and Kathy.

Alfred felt Latinos were more accepted in postwar San Antonio than in Mineral Wells, Avalos says. Nevertheless, he refused to teach their children Spanish.

"The little Mexican kids here were looked down on," Avalos said. "So he said, 'Nope, they'll learn English and they'll be accepted in English.'"

Though she didn’t think it was the right decision, Avalos says it did help her children avoid discrimination.

When their youngest child began grade school, Avalos earned a teaching certificate at San Antonio College and became a kindergarten teacher at a private Baptist school in 1965. Though she loved working with children, she eventually found their parents too demanding.

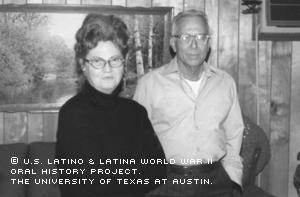

Avalos retired after 15 years. Alfred retired in March of 1976 and died of bone cancer in 1997.

By the time of her interview, Avalos had also experienced her share of health problems: a stroke, cancer and a heart attack, to name a few. But she didn't let it stop her.

She says WWII made her realize how precious -- and how delicate -- life is.

"If you believe in God, it'll take care of itself," Avalos said. "You don't know how fortunate I've been ... I feel taken care of."

Mrs. Avalos was interviewed in San Antonio, Texas, on October 18, 2003, and November 4, 2003, by Karin Brulliard.