By Bernice Chuang

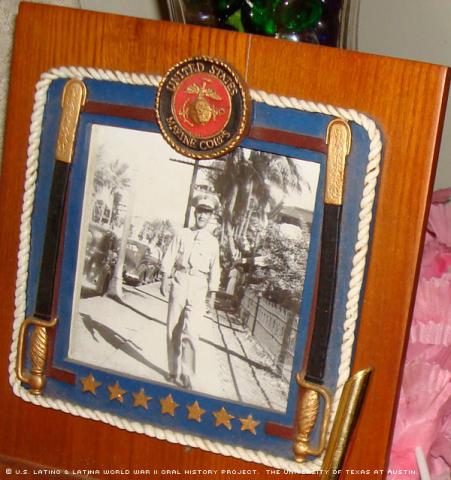

About 14 months before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in December of 1941, Jesus “Joe” Soto, 20 years old, enlisted in the Marines as a private. His ship, the USS New Orleans, deployed for Pearl Harbor in October, just a few months before the attack.

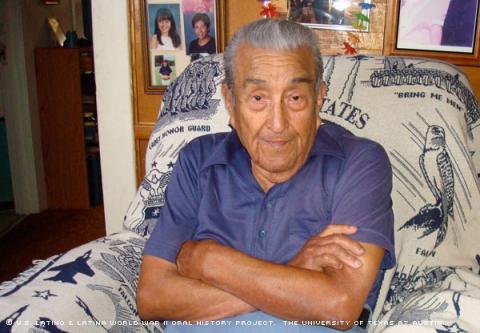

Soto served proudly in the Marine Corps and said he found brotherhood and unity aboard his ship. While the war provided many frightening memories for Soto, he also found pride in his achievements as a Marine.

One of his most frightening recollections was the day Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. “I was shining my shoes that morning before breakfast and the loud speakers sounded,” Soto said. The ship broadcast General Quarters, signaling the men to prepare for battle. Five minutes later, Japanese aircraft zoomed over Pearl Harbor.

A 50-caliber machine gun sat on the deck of Soto’s ship, but it had no ammunition. “Go down and break the lock and get the ammunition,” he said to other crewmembers. By the time the gun was loaded, the Japanese had opened fire and dropped a bomb amidst the U.S. ships.

After surviving the attack on Pearl Harbor, Soto fought in several other Pacific battles, including Coral Sea, Midway, and Eastern Solomons. In 1942, the USS New Orleans met the Japanese at the Battle of Tassafaronga, where the flagship USS Minneapolis was struck by torpedoes and caused the USS New Orleans to steer straight into the track of a torpedo.

“I was about six feet away -- something hit me in the head and shoulders, and I was laying on the deck. I couldn’t move,” Soto said, “The Minneapolis was on fire … torpedoes blew up the whole bow [of the New Orleans], including where I got hit.”

One hundred and thirty-five men were killed on his ship that night. Soto had suffered a head injury and partial hearing loss, and he later received the Purple Heart medal.

“Someone … came and wrapped my head around. We went over to Tulagi, to the tent, and medical officers were there. I didn’t know what was happening,” Soto said.

Soto said he experienced much loyalty and kindness from his crewmembers after his injury. For example, during breakfast, a sailor would sit in front of Soto to help him eat. “We all got along really well,” he said.

“Semper fi,” Soto said, “It means ‘always faithful.’ The Marines say it to each other all the time.”

Soto was born in El Paso, Texas. He was an only child, and he grew up with his Spanish-speaking grandmother, mother, and stepfather. His family was poor, and Soto describes spending most of his time in his childhood with his cousins, playing together and going swimming in the Rio Grande. When Soto was 7 or 8 years old, his family moved to Los Angeles to look for work. It was there that he learned English and attended school.

In the early 1930s, when Soto was in junior high, he joined the Civilian Conservation Corps in California, a part of the New Deal designed to mitigate the suffering of the unemployed during the Great Depression. In return for food, lodging and wages, CCC workers built public roads, facilities and other infrastructure.

“I made $90, and I was the only guy with a suit! I thought everyone else would wear a suit,” he said.

The CCC camps provided work for about three million men, including Latinos, throughout the United States.

One day, Soto walked past a Marines recruiting station. He loved the uniform, so he signed up.

Soto said he did not experience the discrimination and poor treatment that other Latinos may have faced in school or in the Marines. There were about 48 Marines on Soto’s ship and the rest were sailors. Soto says he got along with the other men on his ship and with other Latinos. They went to bars together and smoked, and Soto “asked for a Coke. Never smoked, never drank beer,” he said.

During his time in the Marines, Soto moved up in ranks from private to corporal to sergeant. “Just do the right things -- don’t drink, don’t smoke -- and if they ask you to do something then do it,” said Soto. At one point, Soto was appointed a captain’s orderly and was the only Latino with his rank.

In 1946, after the war had ended, Soto left the Marines for his station in Camp Pendleton on the coast of southern California, and he saw his mother and stepfather again for the first time since he left.

Soto attended Woodbury University in Burbank, Calif., for two and a half years. “I used to make money writing theses,” Soto said. He would sell the typed theses for $40 each.

Before he joined the Marines, Soto met his wife, Otilla Macias, at his cousin’s house in California. They wrote letters to each other while he was at sea on the USS New Orleans for two or three years. They married when he returned to California in 1943.

Soto supported his wife and two children by working at an advertising agency. “I didn’t like it,” he said.

Soto currently lives with his daughter, Joanne Soto Harris, and her family in Alhambra, Calif., east of Los Angeles. His son lives in Santa Ana, Calif., and visits Soto occasionally.

Soto said he does not feel his attitude towards the Japanese is resentful, but he acknowledges there is still social tension between Latinos and other Americans. His only advice for the younger generation is to encourage them to “like other people,” even people who are different from them.

Mr. Soto was interviewed in Alhambra, Calif., on June 8, 2009, by Nancy De Los Santos.