By Lindsey Craun

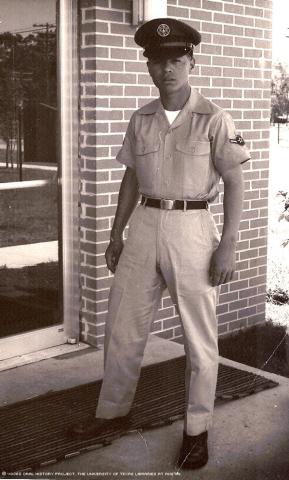

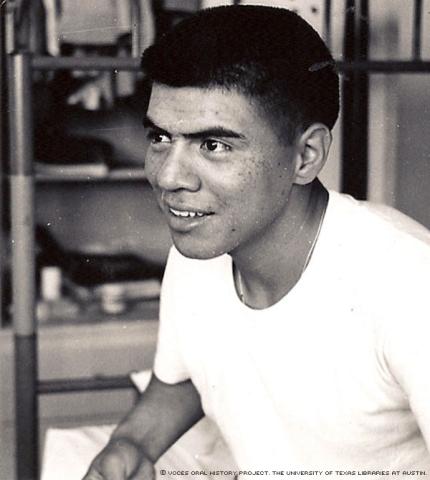

Jim Estrada, a 17-year-old high school dropout, showed up for Air Force technical training in Biloxi, Mississippi.

He was surrounded by college students. But within several weeks, Estrada's intelligence emerged, since he consistently placed in the top 10 percent of his class.

That success represented a turning point in Estrada's life, launching him into a long and prolific career in broadcast journalism, corporate communications and finally his own public relations firm.

"It sort of sparked a fire that, 'Gee, education might be something I want to pursue,'" he recalled.

Estrada was one of eight children his parents raised in San Pedro, a small port community in Los Angeles, California. His father worked in the construction industry while his mother cared for the children. Though he was unaware of it at the time, Estrada said his family was probably on the lower end of the economic strata.

"There was never any lack of food on the table or in the refrigerator," he said. "Everybody had to carry their own weight. Poverty or poor is a relative term."

Beginning in his childhood, Estrada had a passion for learning and education. As a child, he read anything he could get his hands on - even food labels. His mother quizzed him on the contents of various food products around the house. That curiosity continued as he began school at Barton Hill Elementary, where he made consistently good grades, though he rarely felt challenged.

At 14, in an effort to find a creative outlet, Estrada formed his own car painting business and started making his own money. He spray-painted vehicles for family friends, teachers, other students' parents and sailors from the areas' military bases.

He worked after school, and by the time he was 16, he was making as much or more money than his father. He continued his business until the age of 17, when the Air Force contacted him after viewing his impressive enlistment test scores. Estrada dropped out of Abraham Lincoln High School high school in his senior year and joined the Air Force on January 5, 1961.

"I came out of an era where... there was a lot of fighting that was part of growing up, and I didn't think I was headed in the right direction," he said.

Had he not gone in the service, he said, his life might have taken a different turn.

Because of his excellent performance in his technical training, Estrada was given his choice: a field assignment or return to Keesler Air Force Base in Biloxi as a technical training instructor. Estrada stayed four months before seeking a field assignment. He was stationed as a radar technician in Finland, Minnesota, from 1962-1963, where he worked in a small group installing, repairing and testing radar equipment. Estrada's unit briefly travelled to Southeast Asia in 1964 to set up radar equipment for air traffic control -- in preparation for the war that was only then heating up.

After returning to the U.S., Estrada spent a short time stationed in Bellville, Illinois, where he met his soon-to-be wife, Sandra Garcia. The two married when he was 20 and she was 16. After Estrada was honorably discharged in 1965, the couple settled in San Diego.

He returned to painting cars. But the age of 27--and now with two young sons, Raymond and Ron -- Estrada decided he wanted to pursue a college education. He enrolled at Mesa Community College and then moved on to San Diego State University.

"That spark that was ignited in the Air Force, the military, finally came to fruition about seven, eight years later," he said. Estrada said his experience in the military gave him a more mature perspective as he returned to school.

"I think I was a lot more focused, and a lot more serious about learning. I didn't hang out at the quad or the student union," he said. "I was there to study. I was there to do something."

Estrada made the Dean's List his first semester at Mesa and became involved in community activism and civil rights. He was a founding member of Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlan, in 1968, which advocated community-involved education at universities. His involvement in MECHA sparked a long-term passion for encouraging education that would continue throughout the course of his career.

"That sort of turned the corner relative to my politics and my philosophy to get more involvement of our community in a wide range of issues," he said.

In 1971, while working on a degree in broadcast journalism, Estrada landed a job at KGTV, a local television station. Its owner, McGraw-Hill Broadcasting, was looking to diversify the staff.

"I was sort of the answer to this license renewal problem of having diversity on staff," he said. "So I got hired on the spot, and became their sports photographer."

His position at the station shifted over the years and he eventually worked his way into on-air news reporting and then a management position, in which he headed the Community Relations department. In this capacity, he was responsible for expanding the coverage of the African American, Asian American and Latino communities. The station sought to promote community involvement by integrating these groups' perspectives into its programming.

After a few years, he was offered an opportunity to assist McGraw-Hill's president in New York, working on documentary films. He produced several documentaries for the company's six stations across the country, including his former station in San Diego. One of those documentaries, La Raza, was the first television series to explore Mexican Americans. La Raza won many awards, among them the 1972 Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights Journalism Award.

Estrada returned to San Diego in 1975, where he did freelance work for a while and formed an advertising agency, Imagery. In 1982, he was recruited by the McDonald's Corporation to be its regional advertising supervisor for Southern California, Arizona and New Mexico.

After working with McDonald's for nearly six years, one of the nation's top beer companies, Anheuser-Busch, hired him to work in Houston as manager of Corporate/Community Relations. Upon moving to Texas, Estrada noticed an interesting difference between Latinos in California and Texas. He said that the California atmosphere nurtures rambunctiousness in people, and Texas could benefit from his more activist attitude.

"I think it's time for people to start understanding that there's a new sheriff in town, so to speak, in terms of numbers," Estrada said. "And those numbers, by virtue of tax dollars, consumer dollars, votes, has a place that should be assigned to it -- a place at the table. So I think that's why I'm here. God has put me in different places at different times of my life, and I think I'm here right now to see how to help my community develop a voice."

Estrada eventually opened his own public relations firm, Estrada Communications Group, in San Antonio to provide clients with "culturally relevant tools" to address Latinos and their concerns.

At the time of the interview, Estrada was putting final touches on a book, The ABCs and N of America's Cultural Evolution. It was published by Tate on 2013.

"It presents a perspective from a Latino point of view of things that weren't included in history books," he said. "We have 43 Medal of Honor winners that have fought for the United States since the Civil War, but nobody would know that they exist if it wasn't for organizations like [Voces] and for people who take the time and effort to understand who Latinos are."

Estrada's longtime commitment to the community, education and their mutual relationship has taken many forms.

"My notion is that until we start sharing these, people are going to continue to believe what they wish," he said. "Somebody has to challenge the omission of our contributions."

Mr. Estrada was interviewed by Lindsey Craun at The University of Texas at Austin on April 20, 2011.