By Nora Ramirez

World War II is over, but the fight against discrimination is far from finished for Joe Casillas, a WWII veteran who lives in San Diego.

His father, Felix Ledesma Casillas, was a migrant worker who came from Jalisco, Mexico in 1914 and worked in copper mines. Working conditions were terrible so he decided to move, buy land, and build a house.

He moved to Chula Vista, California and bought two acres of land and built the house he wanted for his children. Of nine siblings Casillas, the fifth child, was the first one to be born in that house. He and his six brothers would serve in the military. Joseph served in Europe in the 78th division; Ruben in the South Pacific; Nicolas in the Army Air Corps;, Armando was drafted in the Korean War; Charles in the Marine Corps during the Korean war, Felix in the Air Force at the beginning of the Vietnam war, and Joe Casillas in the Army Air Corps.

In the mid-1940's when he was attending middle school he witnessed the "influx of internal migrants."

"There were people coming from Oklahoma, Texas, Kansas, Arkansas," he said.

They were all migrating to California because there were a lot of jobs working for defense manufacturers. Casillas can recall how the high schools were overcrowded because there were just too many people.

During the war Casillas can clearly remember the day of the evacuation of the Japanese.

"The day after my classroom was half empty because fifty percent of the students were of Japanese descent," he said.

Casillas said he believes the war is what led to the loss of many good teachers.

"It led to the degradation of education-anybody could be a teacher. If it weren't for that those people wouldn't of been able to become teachers at all," said Casillas.

At the age of 16, Casillas went to work for a defense contractor. "They put me in the lousiest, noisiest department there was and that contributed to my hearing loss later in life," Casillas said. He soon left the job and went to work for a produce distributor, a bus company and a brake shop.

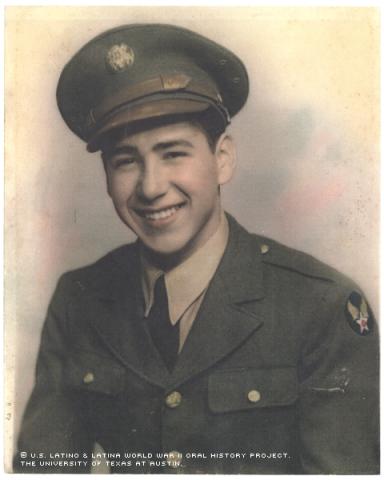

In October 1945, Casillas went to the military. He worked as a radio operator in the area of communications and also served in the strategic air command.

"It was a good experience but it was a waste of time-I could have gone to college," Casillas said. "I belonged to the class of 1946, but I enlisted in the Army Air Corps in 1945, so I didn't get to graduate."

Casillas recalls that he didn't have a good relationship with the officers when he was in the army. He attributes that to the fact that he never got ranked. He said there was a lot of "out of line" behavior that he had a difficult time dealing with it.

His parents were not supportive of the war. His father once told him, "It's a cooked up deal about people [government] making money- - they [government] give a damn about people."

Of course, Casillas decided to join the army anyway. He said, however, that he is proud of his parents and the way they educated them.

"All of us became solid citizens and we never got in trouble," he said.

A school is named after one of his brothers, Joseph Casillas. He was a true hero in the war. He received the Silver Star, Bronze Star, Purple Heart and other awards. Casillas saved his entire squad near Schmidt, Germany. In saving them, he put his life on the line. He endured gunshots to the head and arm and was captured by the Germans for a day. His division picked him up once the Germans evacuated the bunkroom. After a series of surgeries, he survived. A high school in Chula Visa, California was named in his honor.

In 1948 Casillas worked for the Navy as a civilian. He had limited skills so he didn't get a good job. Casillas decided he would enroll in college courses and graduate in order to increase his chances for a better position. Casillas continued to work as a civilian until he moved to the private sector as an engineer. He said he witnessed discrimination while he was there. Later, he helped design the first facility to manufacture guided missiles.

Casillas attended law school for two years, but left to work for the mayor of San Diego, and later, for the executive office of the President. He left his position as region eight director for the office of Economic Opportunity around the time President Nixon was dealing with Watergate. Casillas went back to work for the defense department for nine years, when he retired.

Casillas became an active member of many organizations that addressed discriminatory practices. He has been part of the G.I. Form, MAPA, Chicano Federation, Salvation Army, Civil Service Commission.

He served on the Civil Service Commission of San Diego County for seven years. During that time he managed to propose a ten percent wage increase for those people who were bilingual. They were awarded a 7.5 percent increase, a result Casillas attributes to his absence on the day they made the decision.

Casillas founded his own organization, The North Island Hispanic Association, whose mission is to fight discrimination and promote equal opportunity.

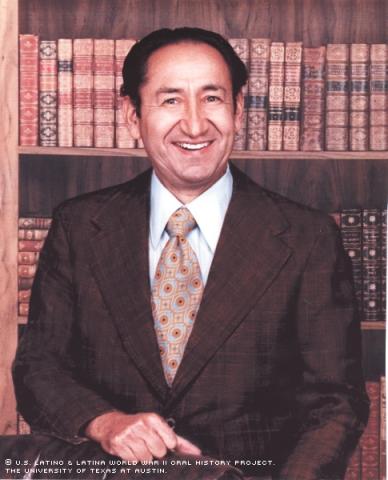

Casillas is the proud father of two children. His son is a medical doctor and his daughter is an attorney. Casillas is married to the former Gloria Castillo.

The feeling of being powerless led Casillas to actively participate in many organizations. He believes that he wants to change things and the only way he can do that is to "get involved to be able to influence the outcome."

"The key to compete is education," Casillas said.